Artists of Color at RAM

RAM is committed to supporting diverse voices—whether that diversity reflects race, gender, sexuality, age, ability, social standing, or world perspective.

In this moment in time, it is critical that spotlights are placed on voices that have been historically underrepresented, at RAM that begins with women and artists of color. Artists of color are identified in this context as non-white and non-European in heritage. This simplification—which is arguably a flawed starting point—does not account for the nuances and variations of society. It is a beginning—a way to direct those who want to educate themselves about what is possible when new perspectives are discovered. Modifications to this approach are expected as RAM learns and grows.

This portfolio highlights the work of artists of color in RAM’s collection. It is not exhaustive and will be built upon over time as more documentation of these artists represented in the collection grows. This effort, similar to efforts to highlight women artists at RAM, is not meant to single out individuals to stigmatize them but to reflect intention, goodwill, and a desire to reckon with years of historical underrepresentation. Further, as an educational institution rooted in the humanities and using art as a catalyst, RAM intends to encourage inquiry and exploration about the world we live in. The museum hopes that spotlighting artists of color spurs further engagement with these artists and their ideas.

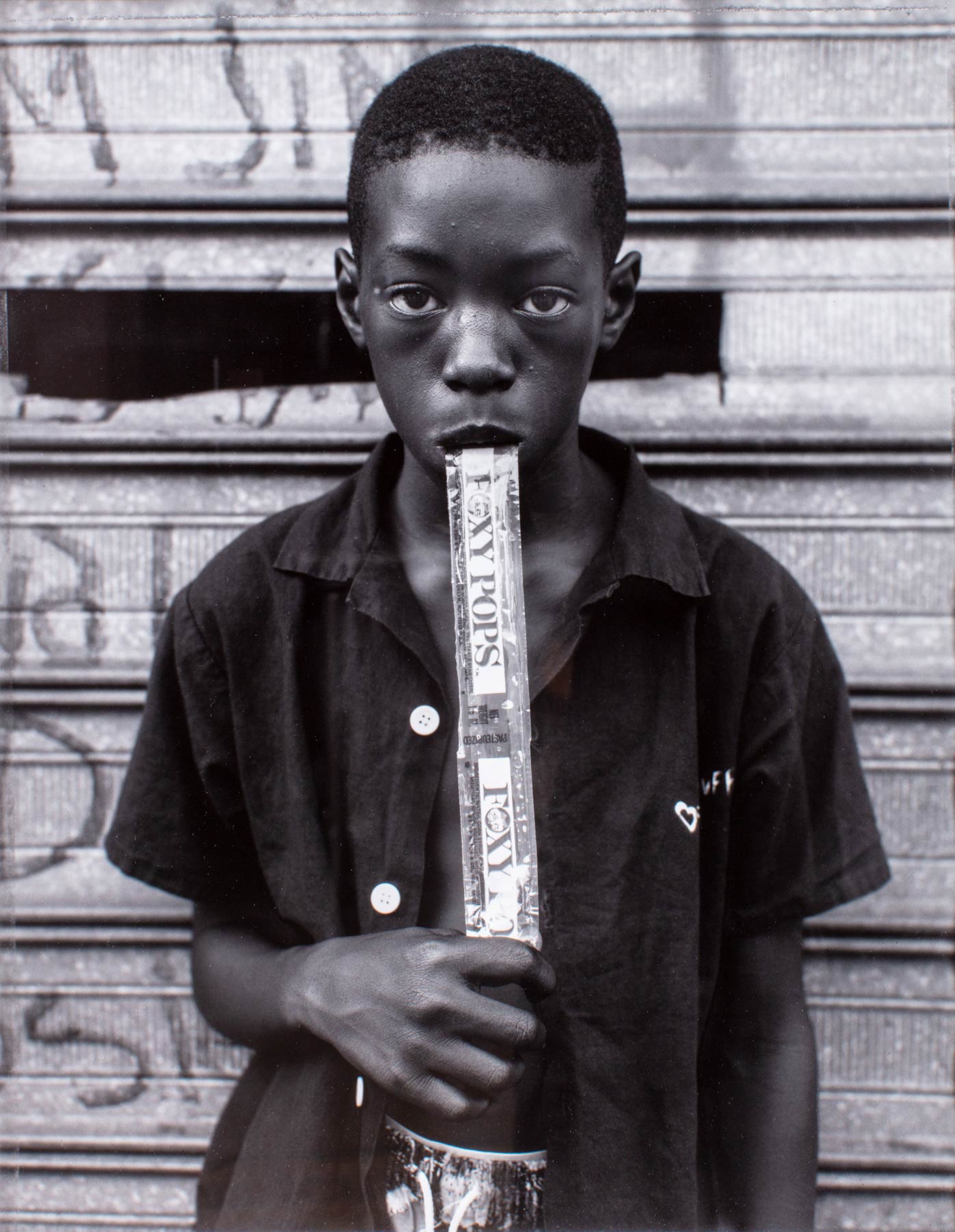

Dawoud Bey

A Boy Eating a Foxy Pop, 1988

Silver gelatin print

12 1/2 x 9 3/4 inches

Racine Art Museum, Gift of Karen Johnson Boyd

I wanted to make photographs that affirmed the lives of ordinary black people in the community that my mother and father had previously lived in… From the time I spent visiting family, friends and relatives there when I was growing up, I knew that with the exception of [Roy] DeCarava’s work, the people of Harlem were often viewed through photographs in terms of social pathology. I wanted to contest the history of those kinds of black representations and also amplify through my photographs the lives of people like my family who still lived there and were making a way.

Currently Professor of Art at Columbia College Chicago and named a MacArthur Fellow in 2017, Dawoud Bey creates photographs that encourage viewers to consider the expansive social and cultural dynamics that shape his subjects. Noting James Van Der Zee, Roy DeCarava, and Walker Evans as motivational figures, Bey was also inspired by photo albums from his family and a sense of social consciousness. Large projects have involved the participation of his sitters, such as youth from communities identified as marginalized, in constructing their own photographed representations. Community, memory, and identity become the focus of Bey’s investigations, even when the images are not formal portraits. Bey’s vision, as well as his expansive approach to building community and opening up the artistic process and institutional parameters, have motivated others to reconsider their own working methods. His work is exhibited and published regularly, and is featured in museum collections in the United States and beyond.

Mike Bird-Romero

Petroglyph Pin, ca. 1990

Sterling silver and 14k-gold

3 7/8 x 1 3/4 x 1/4 inches

Racine Art Museum, Gift of Dale and Doug Anderson

Photography: Jon Bolton

Pueblo artist Mike Bird-Romero, technically self-taught as a jeweler, grew up among creative people. His grandmother, Luteria Atencio, and mother, Lorencita Bird, established significant artistic reputations in pottery and textiles, respectively. Bird-Romero learned basic metalworking skills during middle school and trained himself in later years as he began to pursue jewelry making more seriously. As part of his education and interest, he researched historic Navajo and Pueblo jewelry—sometimes collecting and repairing it—and studied significant contemporary silversmiths. Further examples that inspired him include petroglyphs from canyon walls in the Southwest.

Bird-Romero generously shares his love of jewelry with others and is known for creating bold, sculptural interpretations of traditional Indigenous designs. His process includes, but is not limited to, making his own stamps and dies from old car engines, coiling handmade wire, rolling sheet silver, and cutting and polishing stones.

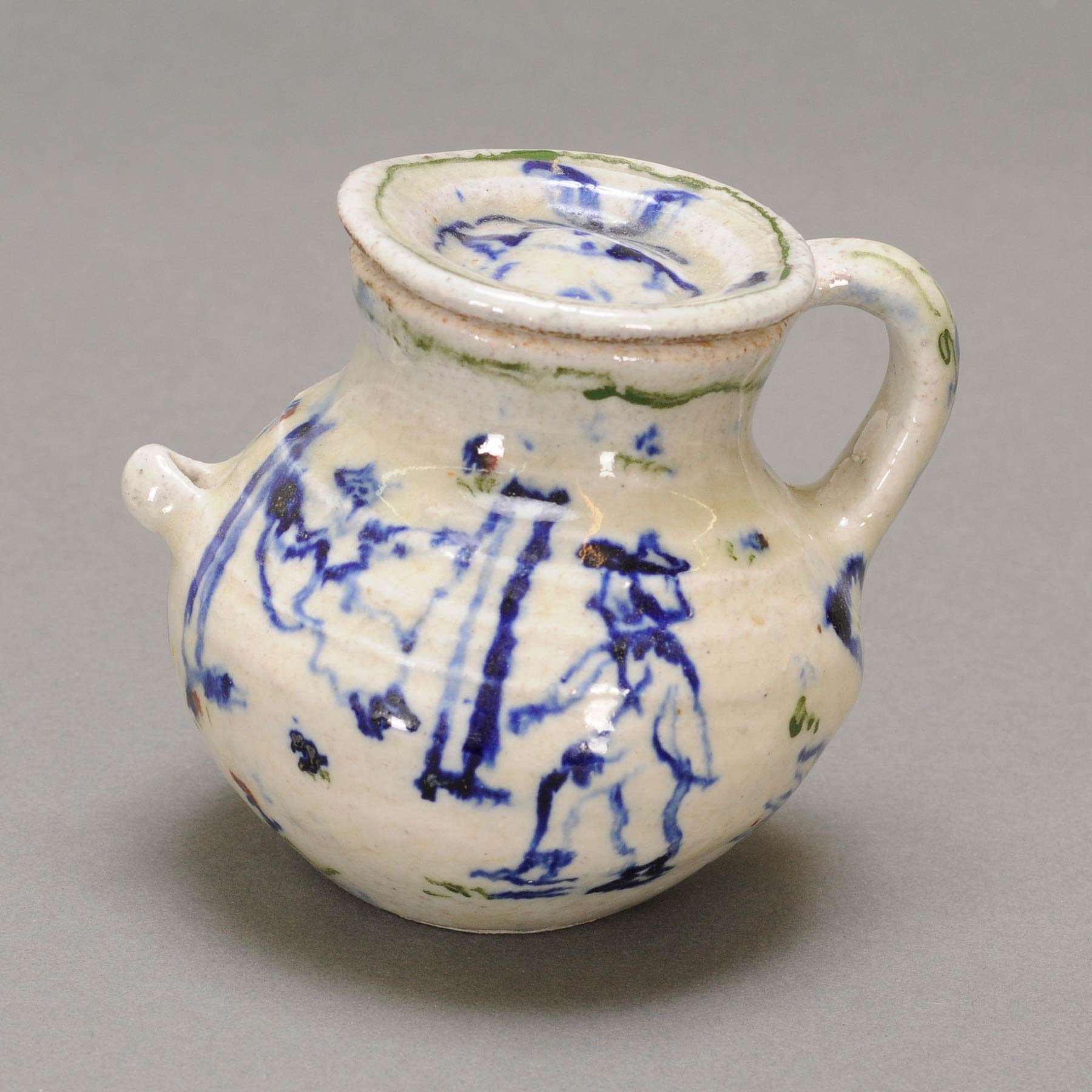

Eddie Dominguez

Fish Dinner, 1987

Glazed whiteware, copper, and wood

Various dimensions

Racine Art Museum, Gift of Donna Moog

Photography: Jon Bolton

I grew up in the small town of Tucumcari, New Mexico. In college I learned that there was a formal, academic way of thinking about art—there was a historical way to think about art, and there were museums all over the world that housed it. I didn’t grow up like that. To me, art was my next-door neighbor making a quilt; it was my aunt crocheting, or my mother making a dress. Anything that involved somebody in any kind of creative expression was art. The most honest influences that I have had can be found in the little things of my home.

Eddie Dominguez is considered a leading figure in contemporary American ceramics, although that is just one of many materials he uses. While his work may sometimes play on notions and objects associated with the domestic, such as dinnerware, Dominguez uses his work to explore the landscape as well as cultural and social issues including ethnicity, political tensions, and gender. His pieces are often shaped by his childhood in New Mexico with its Native American and Spanish colonial past. These influences may show up in his work directly or indirectly alongside other subjects like twentieth-century painting, Asian, African, and Pre-Columbian art, and historical ceramics.

Dominguez’s dinnerware sets, such as Fish Dinner, are microcosmic worlds. While it looks like a colorful ceramic aquarium installed on the wall, Fish Dinner is really comprised of functional plates, bowls, and other serving ware. In a home, the installation could be taken apart and utilized at a dinner party.

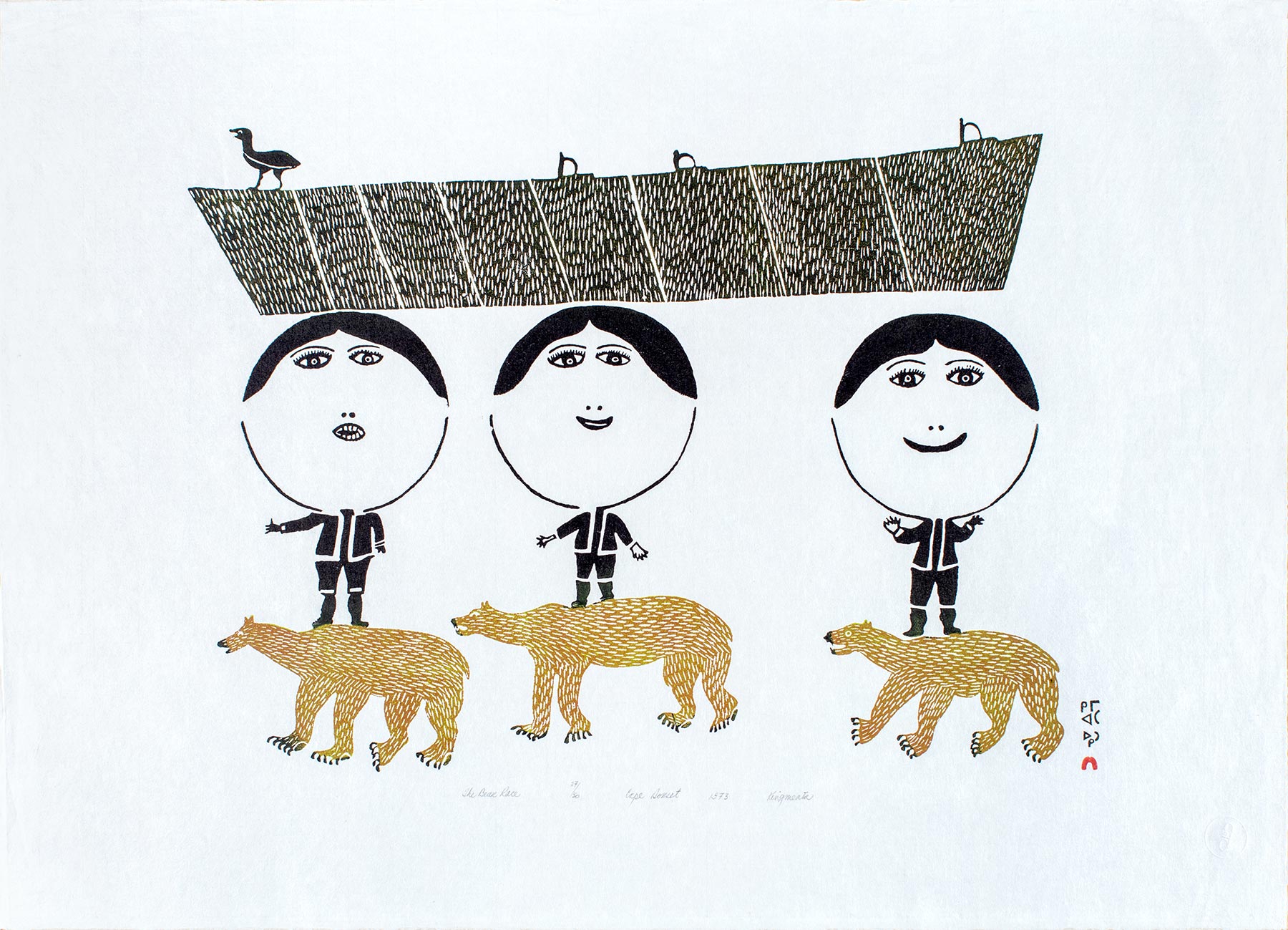

Kingmeata Etidlooie

The Bear Race, 1973

Stonecut, edition 27/50

34 x 24 inches

Racine Art Museum, Gift of Karen Johnson Boyd

Photography: Jon Bolton

Printmaking was introduced to Kinngait (formerly known as Cape Dorset) in Arctic Canada in the 1950s. With purchases being made from cooperatives or artists directly, printmaking as a creative practice has also become a primary economic stream for multiple generations of Inuit artists. Home to America’s largest contemporary craft collection, RAM also has an extensive collection of works on paper that currently includes eight prints from Kinngait artists.

Kingmeata Etidlooie (1915–1989) began to carve and draw after the death of her first husband and became involved in a cooperative known for its printmaking studio with her second husband. Favoring animals and birds as subject matter, she became well-known for her willingness to experiment with materials—incorporating watercolors and acrylics with drawing.

Laritza Garcia

Spun Glass Brooch, 2011

Enamel and copper wire

1/2 x 2 7/8 inches diameter

Racine Art Museum, Gift of Robert W. Ebendorf and Aleta Braun

Photography: Jon Bolton

My personal development and professional training have led me to believe that playful attitudes help people cope, problem solve, and can offer emotional lightness. My jewelry pieces present familiar childhood imagery in efforts to drive forth the restorative nature of imaginative behavior. Gestural objects in vibrant colors materialize as graphic triggers that reconnect people with regenerative powers of playfulness. My approach encompasses a dual investigation of gestural drawing and traditional metalworking practices such as hand piercing metal. I use inks and calligraphy brushes to make linear illustrations that are the base from which ideas are developed into refined pieces of adornment. The intent of this body of work is to infuse wardrobes and activate walls with whimsical pieces that bring levity to the forefront.

Originally from the border area of Reynosa, Mexico, and McAllen, Texas, Laritza Garcia values her involvement in youth outreach—as well as painting and illustration—as an influence on her jewelry design. She received a BFA from Texas State University and an MFA from East Carolina University. In addition to being a studio jeweler and participating in juried craft shows, she has been a visiting artist at locations across the country and teaches in the School of Art and Design at Texas State University.

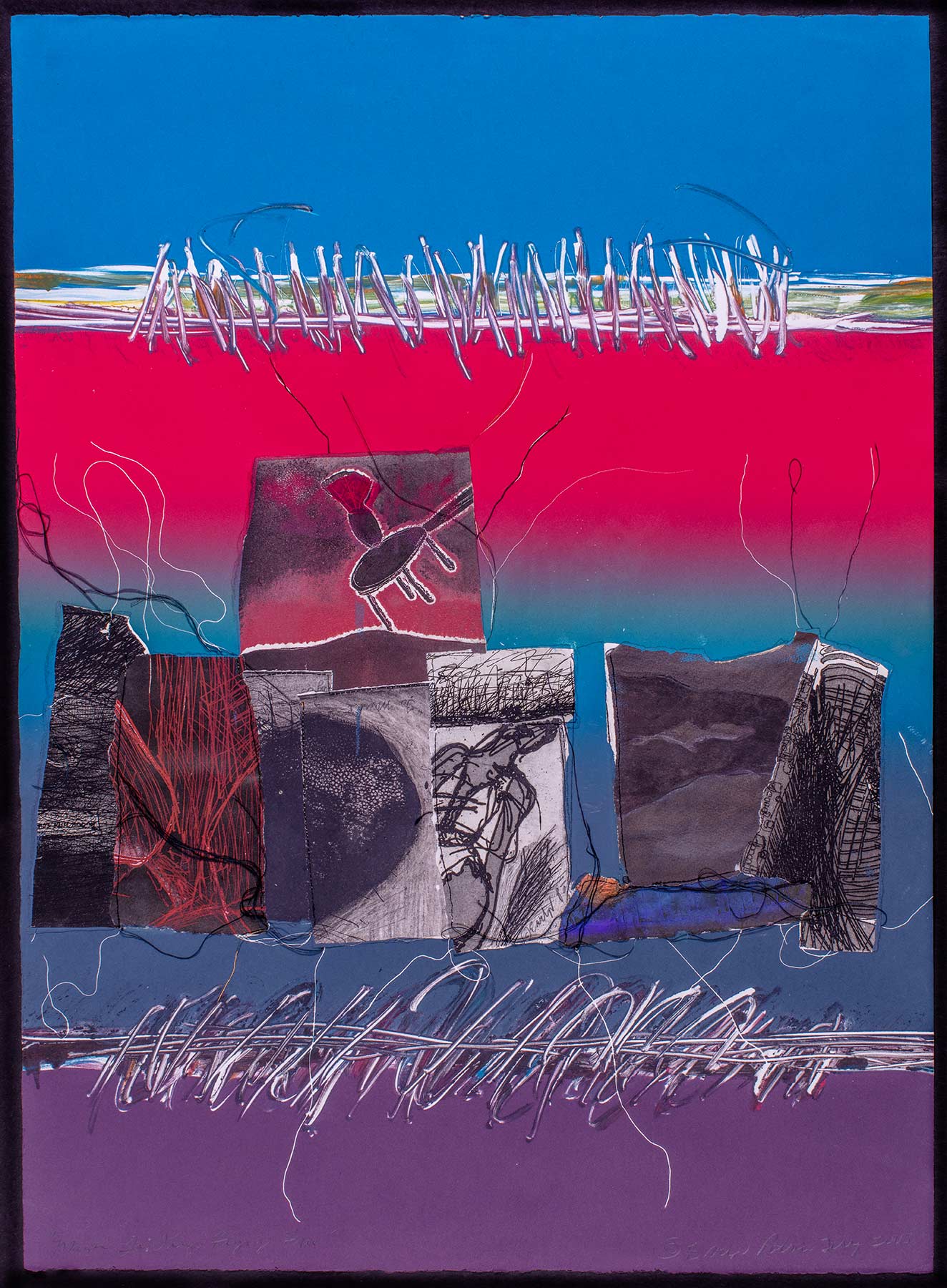

Sam Gilliam

Bardstown, 1976

Color collograph on handmade paper, edition 20/25

22 x 22 inches

Racine Art Museum, Gift of Karen Henrietta Keland

Photography: Jon Bolton

Influential artist Sam Gilliam is represented in RAM’s collection through an etching entitled, Bardstown, from 1976. The following two descriptions of Gilliam and his work reflect two different ways of understanding the complexities of how artists are perceived and how those perceptions may—or may not—impact their artwork.

Sam Gilliam is a color field painter who became internationally famous in the 1960s for draping his innovative and colorful canvases across walls and suspending them from ceilings without rigid supports and frames. He is among the relatively small number of African American artists who have chosen to paint works with no recognizable subjects despite pressure from influential African Americans to paint works that represent their shared experience. Gilliam has made clear that he will not give up his commitment to abstraction to meet other people’s expectations or desires…Gilliam claims he intends no specific, racial meaning(s). Abstraction, he insists, conveys a power far greater than any political theme.

—Smithsonian American Art Museum

Sam Gilliam is one of the great innovators in postwar American painting…Suspending stretcherless lengths of painted canvas from the walls or ceilings of exhibition spaces, Gilliam transformed his medium and the contexts in which it was viewed. As an African-American artist in the nation’s capital at the height of the Civil Rights Movement, this was not merely an aesthetic proposition; it was a way of defining art’s role in a society undergoing dramatic change. Gilliam has subsequently pursued a pioneering course in which experimentation has been the only constant.

—Pace Gallery, New York

Manuel Hughes

Scat Series #3, 1991

Oil on paper

15 1/4 x 18 1/4 inches

Racine Art Museum, Gift of Stefanie Juster Gothelf

Photography: Jon Bolton

A collector of the objects he paints, Manuel Hughes strives to capture the essence of the things that grab his attention—namely, antique cans, toys, instruments, tin, and fabric. Hughes has been active in the art world since the early 1970s, with more than three decades spent teaching at Pratt Institute’s School of Design, Brooklyn, New York.

Currently Hughes—who divides his time between New York City and Paris, France—explores antique shops and thrift stores while maintaining an active studio practice. Recently interviewed for a podcast, Hughes noted that he does not paint every single thing he finds, preferring to focus on the things he finds the most “beautiful.”

RAM has one painting by Hughes in the collection. Filled with antique tin cans and rusted signage, the piece reflects the artist’s long-term interests. Hughes has further played with illusion, creating more abstracted compositions such as a series of works focused on bits of colored ribbon—and the shadows they made—arranged on a solid background. Significantly, responding to his heritage, Hughes has highlighted social issues by painting metal signs with the words, “African-American, “Black,” and “Colored Women.”

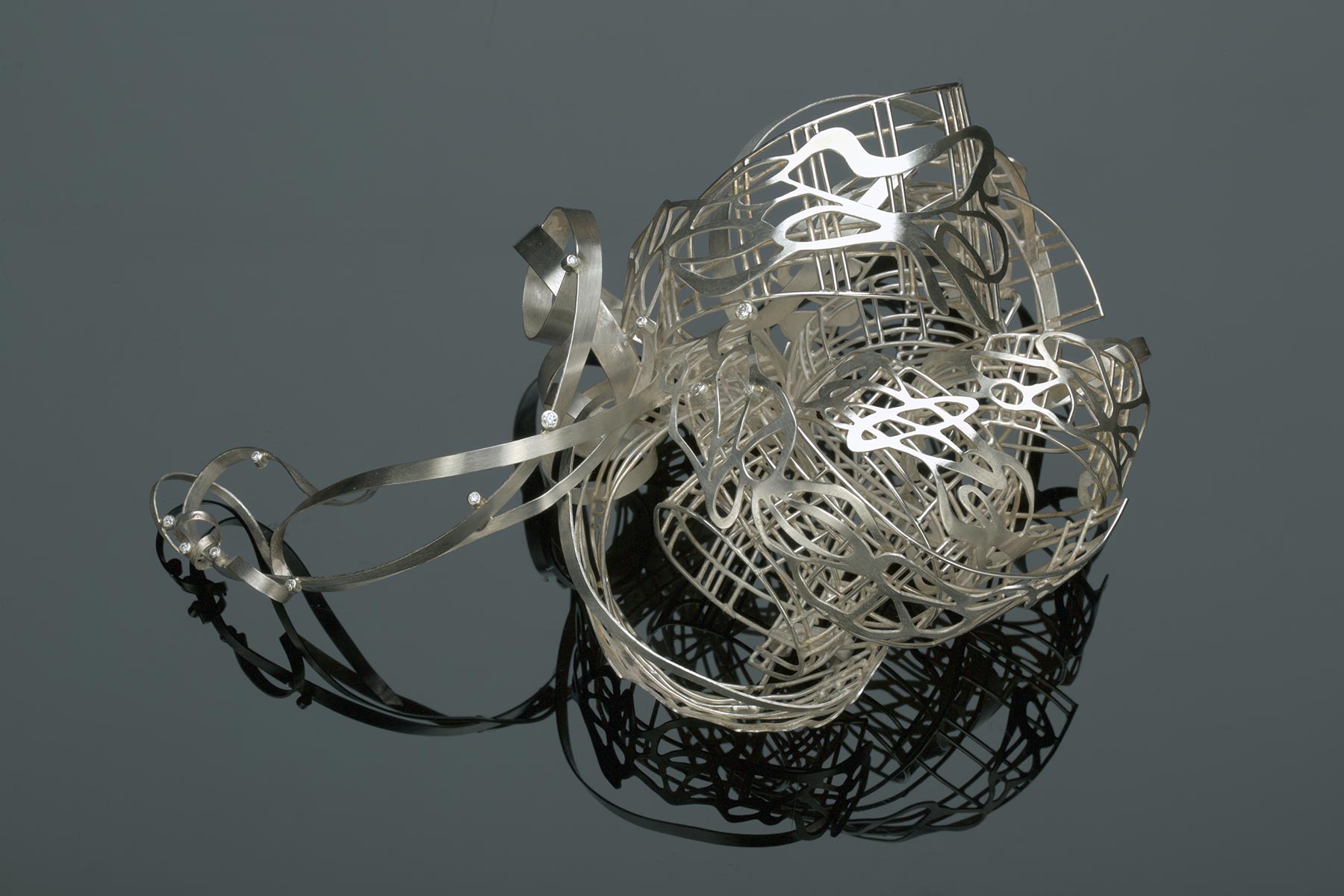

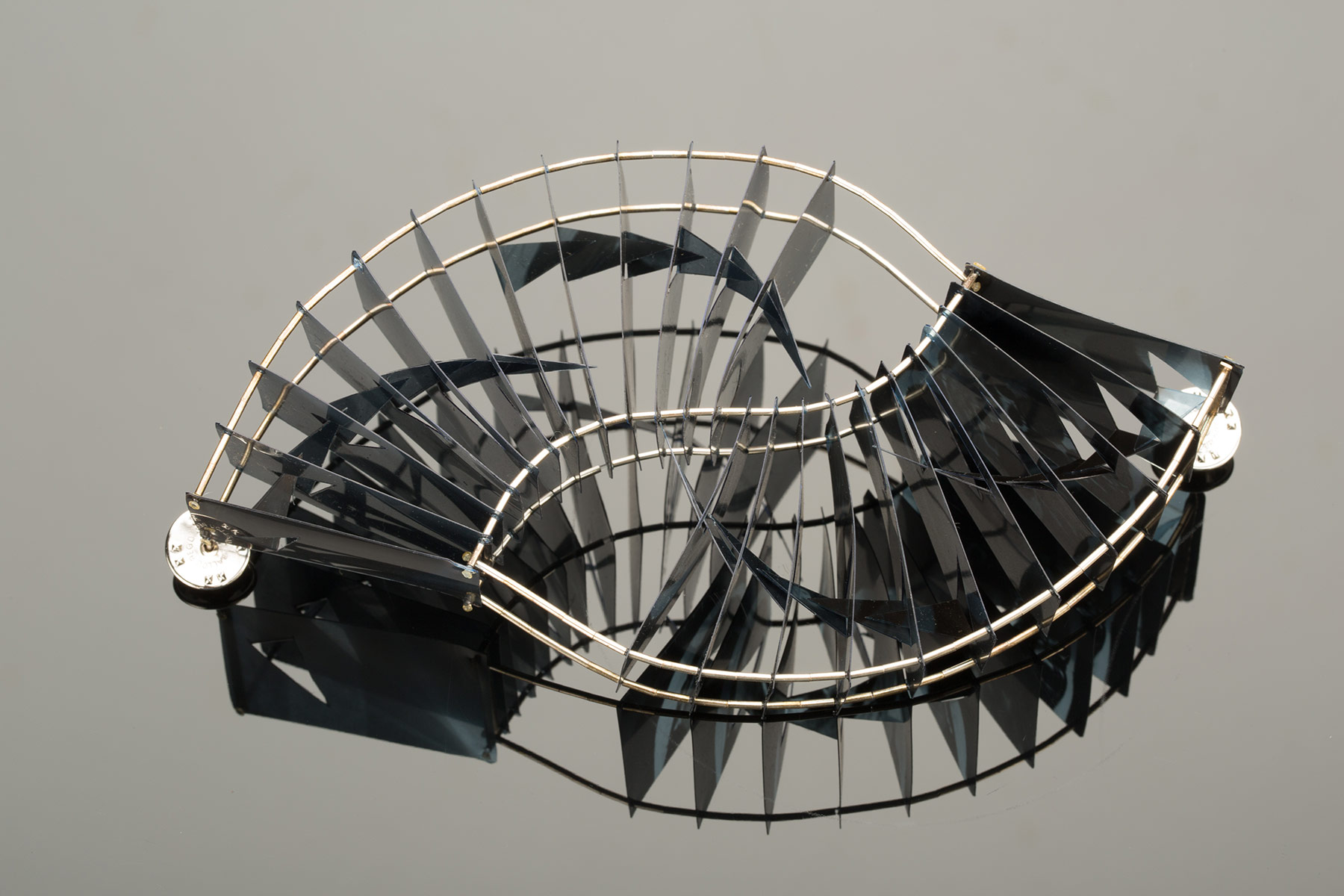

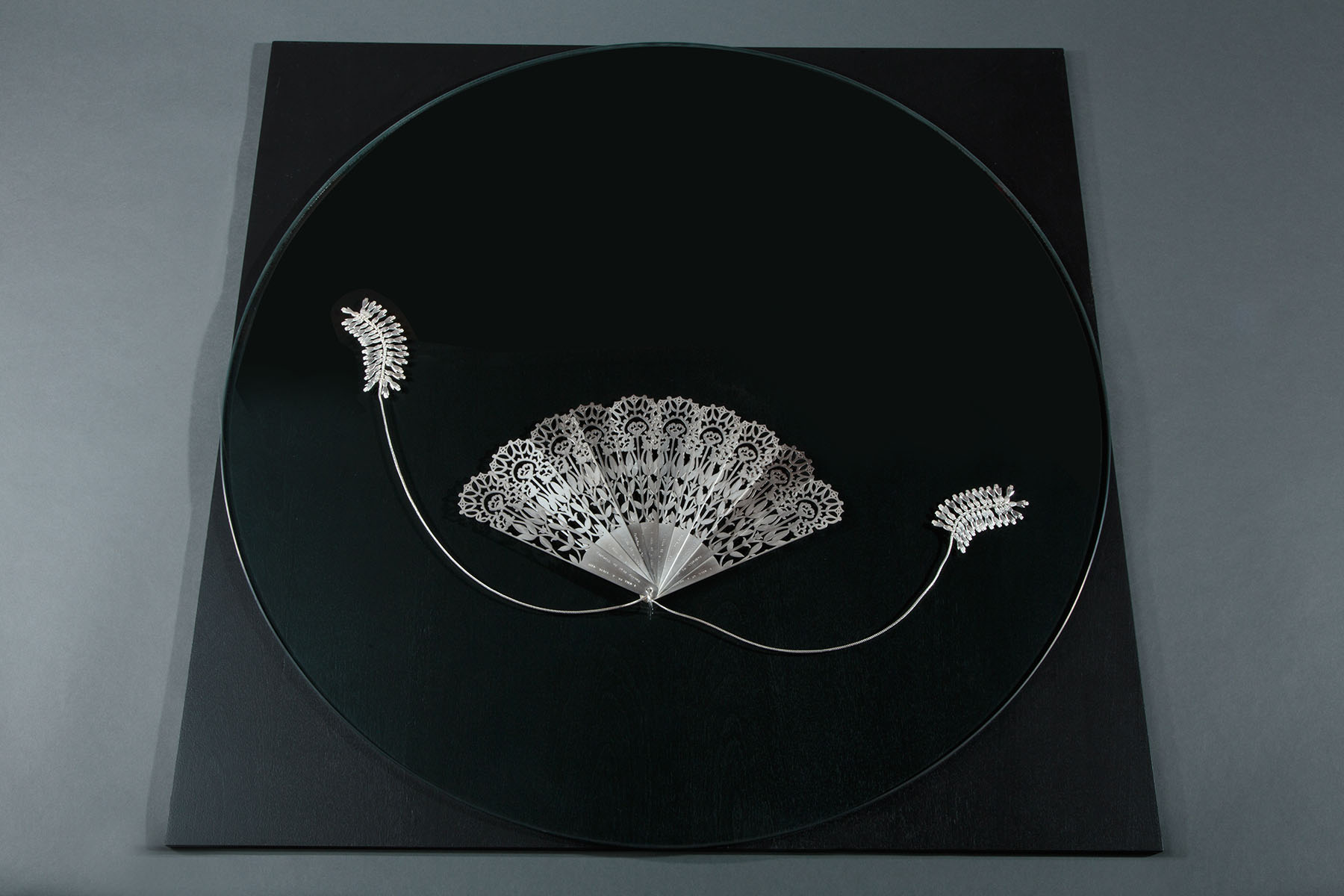

Hai-Chi Jihn

Mother, a Beautiful Young Lady, 2000

Sterling silver, glass, and wood

Racine Art Museum, Gift of Dale and Doug Anderson

Photography: Jon Bolton

Utilizing exacting metalsmithing processes, Wisconsin-based artist Hai-Chi Jihn creates sculpture that addresses her Chinese heritage, issues of femininity, and women’s perceived social roles. Born in Taiwan, Jihn earned a BA in textile and clothing design from Fu Jen University in Taiwan and an MFA in metalsmithing from UW-Milwaukee.

Mother, A Beautiful Young Lady, a fan sculpted by Jihn from silver and inscribed with text is featured in RAM’s collection. With elements constructed to look like lace, this piece is connected to other works she has created that use the idea of dowry—gifts given to a prospective bride’s family—to investigate the complex circumstances associated with marriage beyond love or companionship. The text, which Jihn describes as a “bride’s promise to her parents before she sets off to the wedding,” repeats on blades of the fan. It reads:

Farewell my dear father,

I will be a loyal wife;

Farewell my beloved mother,

I will be a diligent wife.

Luis Jiménez

Chula, 1987

Color lithograph, edition 13/80

22 1/4 x 29 1/2 inches

Racine Art Museum, Gift of Marshfield Clinic and Kohler Foundation, Inc.

Photography: Kohler Foundation, Inc.

I want to create a popular art that ordinary people can relate to as well as people who have degrees in art. That doesn’t mean it has to be watered down. My philosophy is to create a multilayered piece, like [novelist Ernest] Hemingway’s “Old Man and the Sea.” The first time I read it, it was an exciting adventure story about fishing. The last time, I was deeply moved.

Most famously known for his large-scale public sculpture that both drew from and challenged others perceptions of Mexican-American culture, Luiz Jiménez (1940–2006) also created numerous prints and drawings. Jiménez gained exposure to various materials and processes at a young age when he worked in his father’s neon sign-making shop. His perspective combines what he describes as his “working class roots” and familial Mexican heritage with practical experience and the study of Mexican, American, and European art traditions.

A careful observer of social dynamics, Jiménez often employed a satirical approach to his subject matter—a fact that also made him and his work targets for controversy at various points. Chula, one of two of his prints in RAM’s collection, hints at how he could build layers of meaning. In the piece, Jiménez depicts a Great-tailed Grackle, a bird native to the Southwest and Texas known for its blue coloration, distinctive call, urban dwelling, and boisterous behavior. The suggestion is that the word Chula—a Spanish word generally used to describe a pretty woman–that is included at the bottom of the print is the sound the bird is making. In this sense, Jiménez is highlighting the flamboyant behavior of “street-wise Latino men who deliver catcalls to Latino women.” Coincidentally, or not, Chula was also the name of one of the two ravens that Jiménez had as companions for some time.

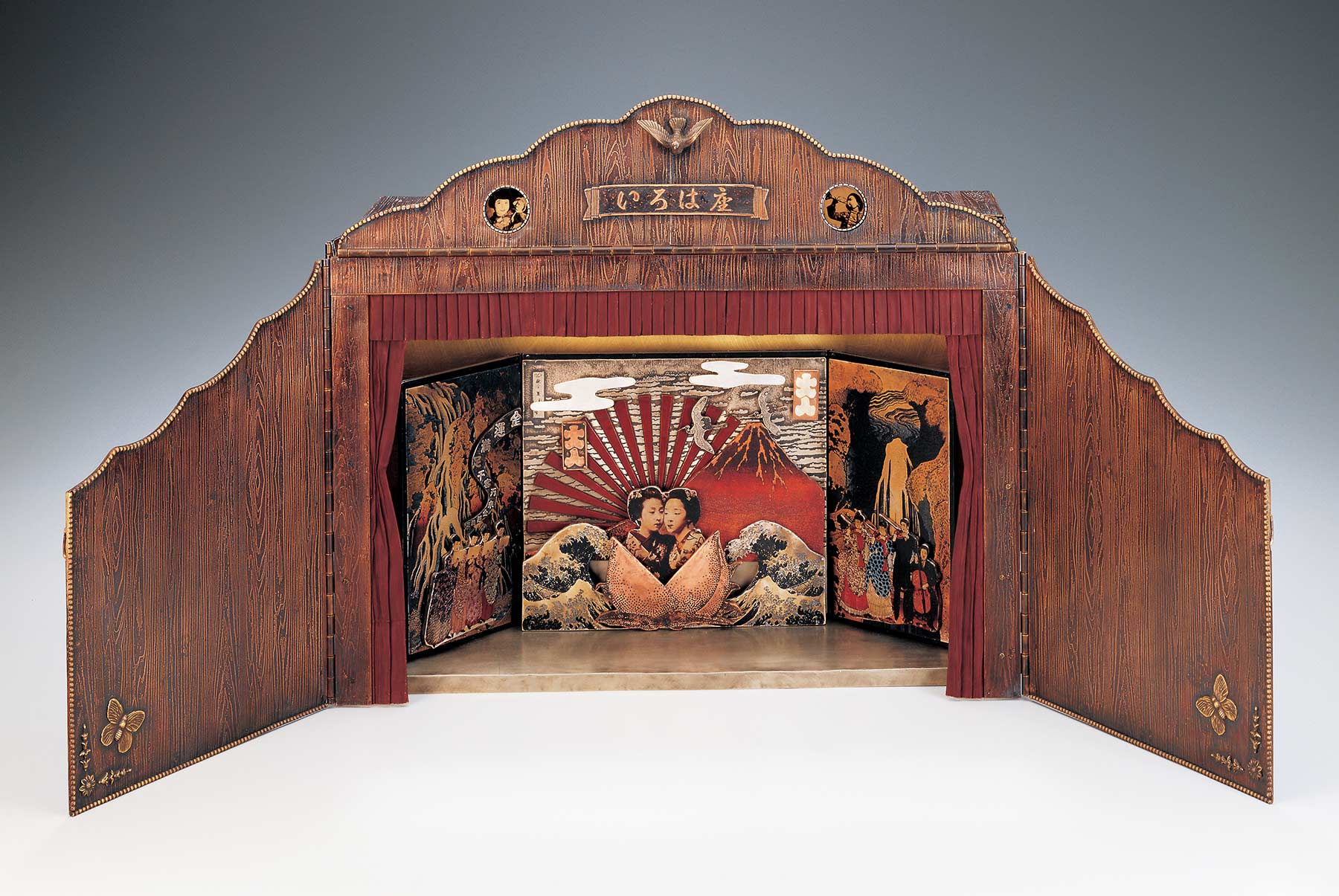

Mariko Kusumoto

Byobu, 2004–06

Copper, nickel, silver, brass, sterling silver, magnets, and artist-rendered decals

15 x 30 x 9 1/2 inches

Racine Art Museum, Gift of Karen Johnson Boyd

Photography: Johansen Krause

Growing up in a 400-year-old temple, I was always surrounded by ancient things like tansu (Japanese chests of drawers), faded paint on wood, Buddhas and their ornaments, etc. I was especially fascinated by the tansu. When I opened the drawers, I could never anticipate what would appear from the darkness. I had mixed feelings of excitement and fear whenever I opened it. It was a great wonder box to me.

Artist Mariko Kusumoto creates magical worlds that both delight and mystify. Using a variety of metalsmithing techniques, She crafts elaborate miniature stage sets with multiple doors, moving parts, compartments, and drawers as well as the characters and props to inhabit them. Her love of theater and performance is underscored by the potential interactive elements of each piece—they can be presented as closed boxes and containers, or opened and manipulated so that their stories unfold. The narrative potential is even more complex as many elements are created in the form of brooches, necklaces, and bracelets that can be worn and thus seen in a wholly different light. These metal sculptural boxes, which also incorporate found objects, reflect Kusumoto’s Japanese identity and influences from her childhood. For several years, Kusumoto has also been making fiber work, especially adornment such as neckpieces that look like bubbles and organically-inspired brooches. She has stated that she likes the contrast between the types of materials she favors, where fiber is almost the “opposite” of metal.

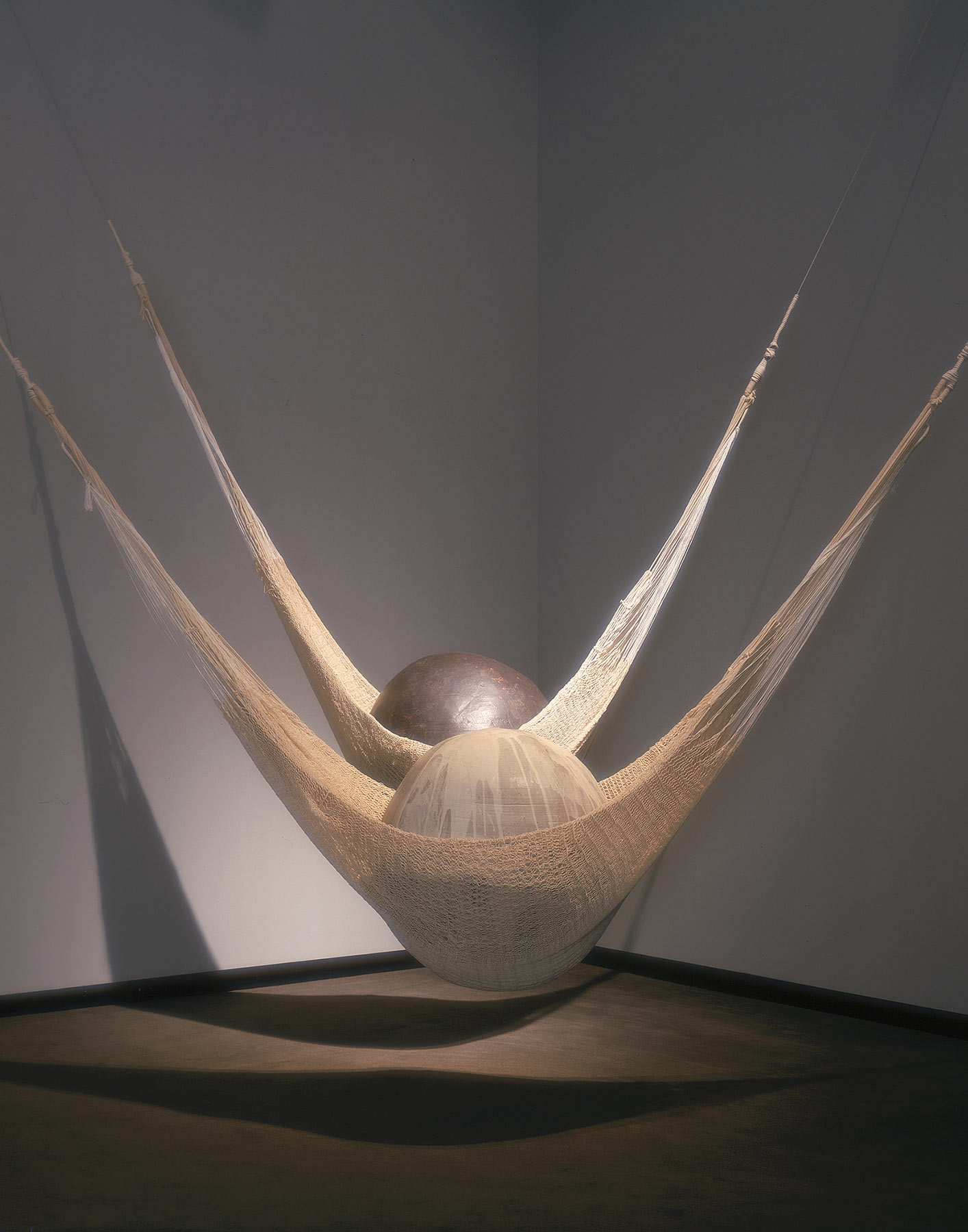

Ke-Sook Lee

Apron #4: Seed Pods, 2004

Rice paper, embroidery thread, tarlatan, doilies, and earth pigment

65 7/8 x 55 1/2 inches

Racine Art Museum, Gift of Barbara and Steven Gross

Photography: Jon Bolton

Born in South Korea, Ke-Sook Lee—who is now based in California—moved to the US in 1984. Lee earned a BFA from Seoul National University in Seoul, Korea in 1963 and another BFA from the Kansas City Art Institute, Kansas City, Missouri, in 1982. Her work is exhibited and collected internationally.

Wanting to focus on womanhood, Lee moved away from painting and began to work with fibers. Over time, she expanded the scale and scope of her pieces, moving towards large work and installations. Lee focuses on domestic themes and aspects of the natural world, often as metaphors and parallels to life experiences. Her work purposefully draws on generations of familial, female-oriented history.

As noted in a statement about her work:

The women of her grandmother’s generation who were not taught to write instead expressed themselves through hand-embroidery. As she makes her marks, she focuses on the experience of sewing, stating, “I am interested in relinquishing conscious control of my hand, letting the thread and needle respond to my memory and experience of my womanhood.”

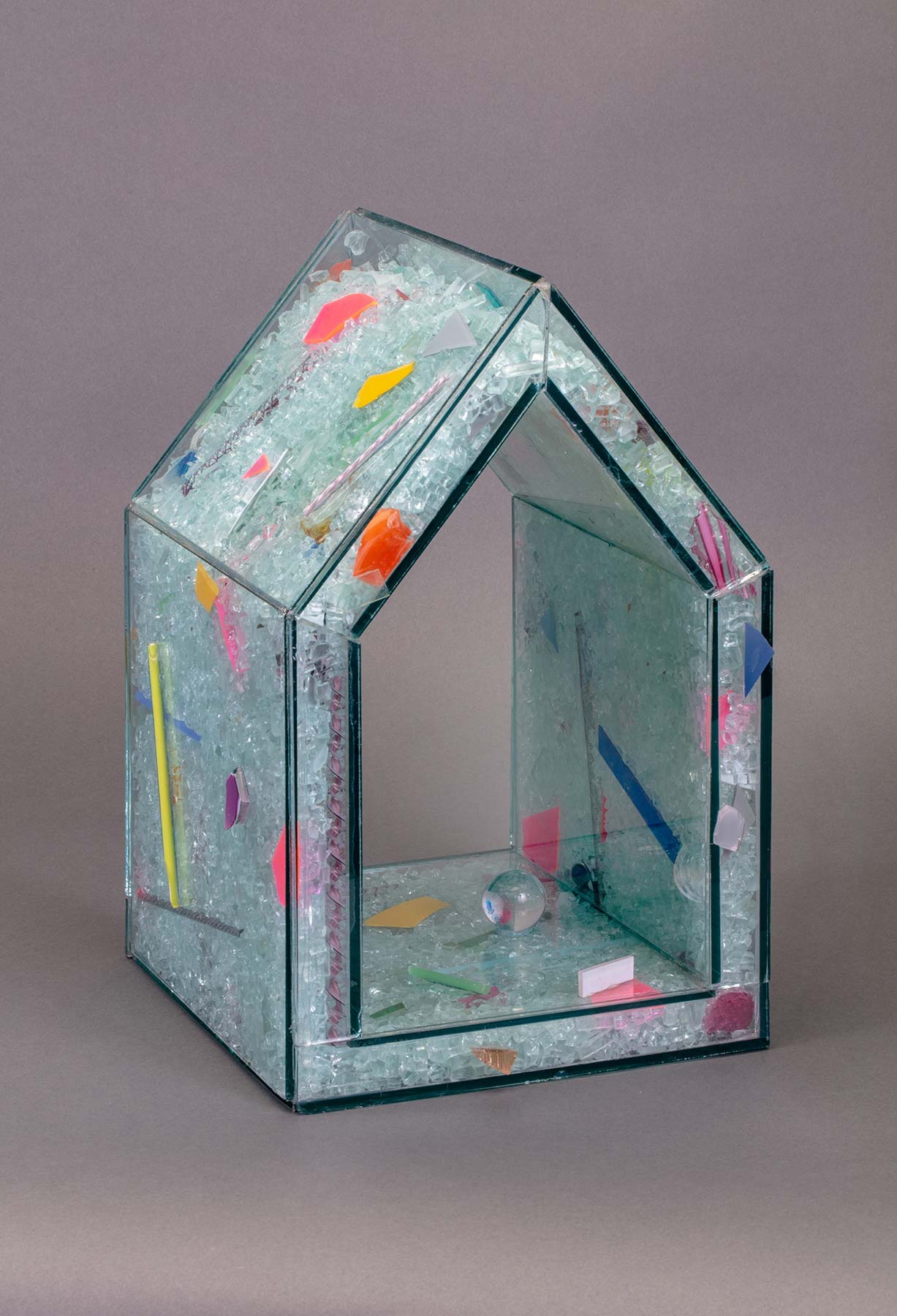

Silvia Levenson

Panchina Di Vetro (Bench of Glass), 2002

Glass, metal, and AstroTurf

20 x 47 3/16 x 10 1/8 inches

Racine Art Museum, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

Photography: Jon Bolton

I was born in Buenos Aires in 1957. I was part of a generation that fought to change a society that we perceived as terribly unfair. In 1976, when the Army seized power, I was nineteen…What happened between 1976 and 1983, changed my life, and influenced my work as an artist. A key part of my job consists of revealing, or making visible, what is normally hidden or cannot be seen, and I use glass to represent this metaphor. We have always used glass to preserve food and drinks, I use glass to preserve the memory of people and objects for the future generations.

Silvia Levenson left Argentina in her early twenties amidst political unrest and family tragedy. While her work can sometimes consider the domestic, daily life, childhood, social expectations, and fashion, it is rooted in her personal experiences and the universality of the human condition. Fascinated with the beauty of glass as a material, Levenson is compelled to push past its aesthetic, engaging its potential to convey the content she explores in her work.

RAM currently has three works by Levenson in the collection.

Holly Anne Mitchell

The Joke’s On You! (Bracelet), 1992

Found colored newspaper, brass beads, elastic, and cotton cord

1 3/4 x 5 x 2 1/2 inches

Racine Art Museum, Gift of Dale and Doug Anderson

Photography: Jon Bolton

For 30 years, I’ve had an endless fascination with newspaper. It began with an assignment in a metalsmithing class to create a piece of jewelry which did not consist of any traditional materials (no metal, precious stones, etc.). I chose newspaper. I love to push the boundaries of its text, color and content… I use Comic Strips because the characters’ expressive faces contain bold, bright and powerful colors. I use Expired Coupons because the textural patterns of many elements including the UPC Bar Codes are reminiscent of African Kente cloth. I strive to bring out these aesthetic strengths to create jewelry which is equally interesting both on and off the body. I truly believe the ordinary (such as newspaper) can be extraordinary.

Holly Anne Mitchell uses recycled newspaper to create beaded bracelets, brooches, necklaces, and earrings that speak to eco-friendly practices as well as challenge assumptions about which materials can be used for jewelry. Mitchell is inspired by social and cultural issues as well as material and aesthetic ones. The tone of her work can range from playful—as is the case with Mitchell’s bracelet in RAM’s collection, The Joke’s On You!––to serious. Her I Can’t Breathe Neckpiece incorporates newspaper with articles and images regarding the death of George Floyd. As she states:

It is a direct reflection and expression of my emotional response to this horrific, senseless death. As an African American, I felt a deep connection to Mr. Floyd. If it happened to Mr. Floyd, it could certainly happen to any and every African American man in my life.

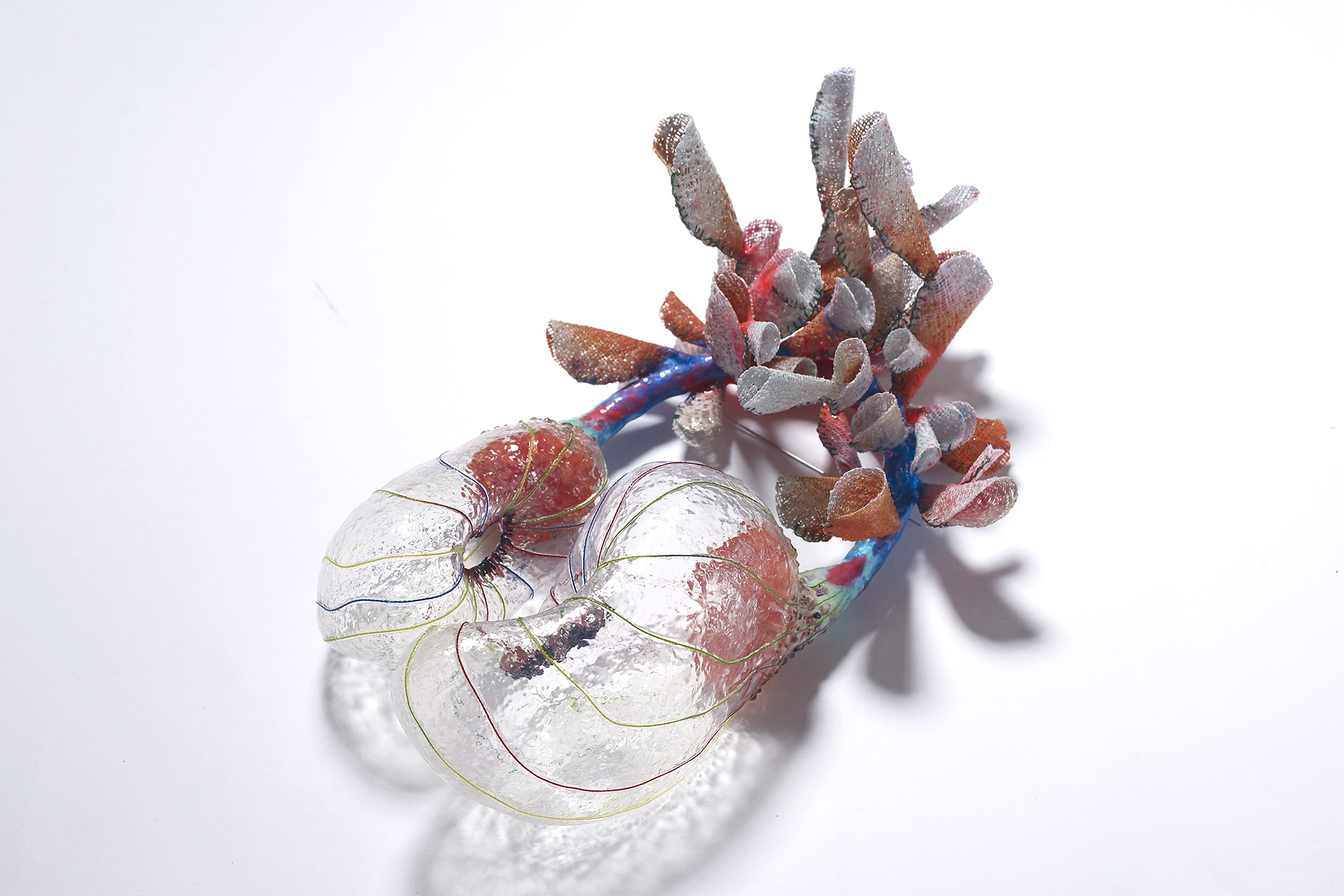

Keisuke Mizuno

Purple Flower, 2001

Glazed porcelain

4 3/4 x 10 1/4 x 9 3/4 inches

Racine Art Museum, Gift of Devra Breslow

Photography: Jon Bolton

That’s what I want to do, draw you into the piece and then I’ve got a surprise for you.

Keisuke Mizuno is now most interested in investigating geometric form. His earlier work, such as this piece in RAM’s collection, reflects his fascination with, in his words, “the beauty of the inseparable dependence and visual disparity between life and death.”

Exploring the transitory nature of existence and purposefully echoing historical traditions of memento mori—artistic or symbolic reminders of the inevitability of death—Mizuno crafts porcelain flowers and fruit in various stages of bloom and decay. His inclusion of curled edges, devoured portions, and sometimes, miniature skulls reflect his interest in the cycles of nature. Mizuno’s choice of material—with porcelain being both resilient and fragile—function as a metaphor for his larger ideas.

Mizuno was born in 1969 in Nayoga, Japan. He studied at the State University of New York-Buffalo before receiving a BS from Indiana State University. After some time at the Kansas City Art Institute, Kansas City, Missouri, he earned an MFA from Arizona State University-Tempe. Mizuno currently teaches ceramics at St. Cloud State University, St. Cloud, Minnesota.

Francisco X. Mora

Little Red Riding Hood, 2009

Acrylic paint

Racine Art Museum, Ruth Miles Memorial Purchase Award from Watercolor Wisconsin 2010

Photography: Jon Bolton

It seems that I was born drawing. Since as long as I can remember, a pencil or a crayon has been in my right hand. These are as familiar to me as part of my body.

Inspired by the imagery and content of folk stories and music from his native Mexico, Milwaukee-based Francisco X. Mora constructs his own fanciful narratives that are a blend of personal and cultural references. He incorporates characters that are derived from excerpts of Mexican mythology, popular stories, or his own dreams and memories. In addition to producing prints and paintings, Mora writes and illustrates children’s books that also include adaptations of folk tales and legends. For decades, he has been involved in children’s education programs, drawing from his skills as a storyteller and his knowledge of art and music.

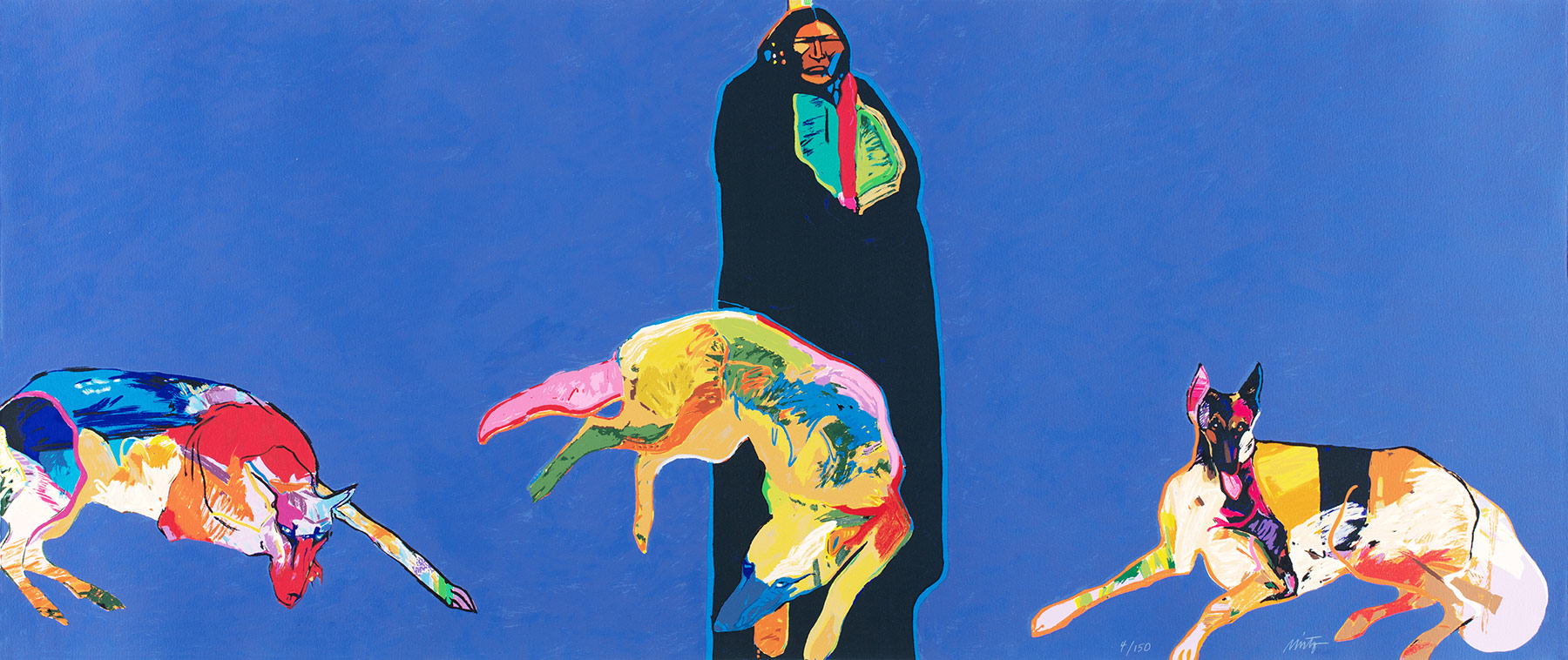

John Nieto

Untitled (Man’s Best Friend), ca. 1995

Color serigraph, edition 4/150

17 1/2 x 41 1/4 inches

Racine Art Museum, Gift of Larry and Mickey Magid

Photography: Jon Bolton

I employ a subject matter that is familiar and express it the way I see it.

Contemporary artist John Nieto‘s (1936–2018) background directly influenced the style and subject of his work. Known for bold images with intense color blended with solid, expressive lines, Nieto focused on subjects that were commonplace in his New Mexico home. His paintings, prints, and drawings included animals, figures, and iconography associated with indigenous people from the Southwest.

Nieto’s mother was of Apache and Hispanic descent, and his father became a Methodist minister. He uses this layered history—one that has rooted his family in New Mexico for over 300 years—to draw attention to the region’s dynamism.

Etsuko Nishi

Lace Cage Bowl, 1992

Glass

5 3/4 x 11 3/4 inches diameter

Racine Art Museum, Gift of Dale and Doug Anderson

Photography: Jon Bolton

Glass artist Etsuko Nishi creates sculpture that operates in ambiguity, suggesting something natural or abstract. Drawing on an appreciation for nature, including its variability, she prefers to craft non-representational vessels and forms.

Nishi has spent years experimenting with techniques and is well-regarded in contemporary art for her interest in reviving the exacting process of pâte de verre (glass paste). In simplified terms, producing pâte de verre works involves preparing a negative mold, applying a paste of glass and binding material to it, and heating the mold so that the granules fuse together.

Nishi, who was born in Kobe, Japan, earned a BA from Mukogawa University–Japan before studying at the Pilchuck Glass School in Seattle. She holds a master’s degree from the Canberra School of Art, Australia, and a PhD from the Royal College of Art, London.

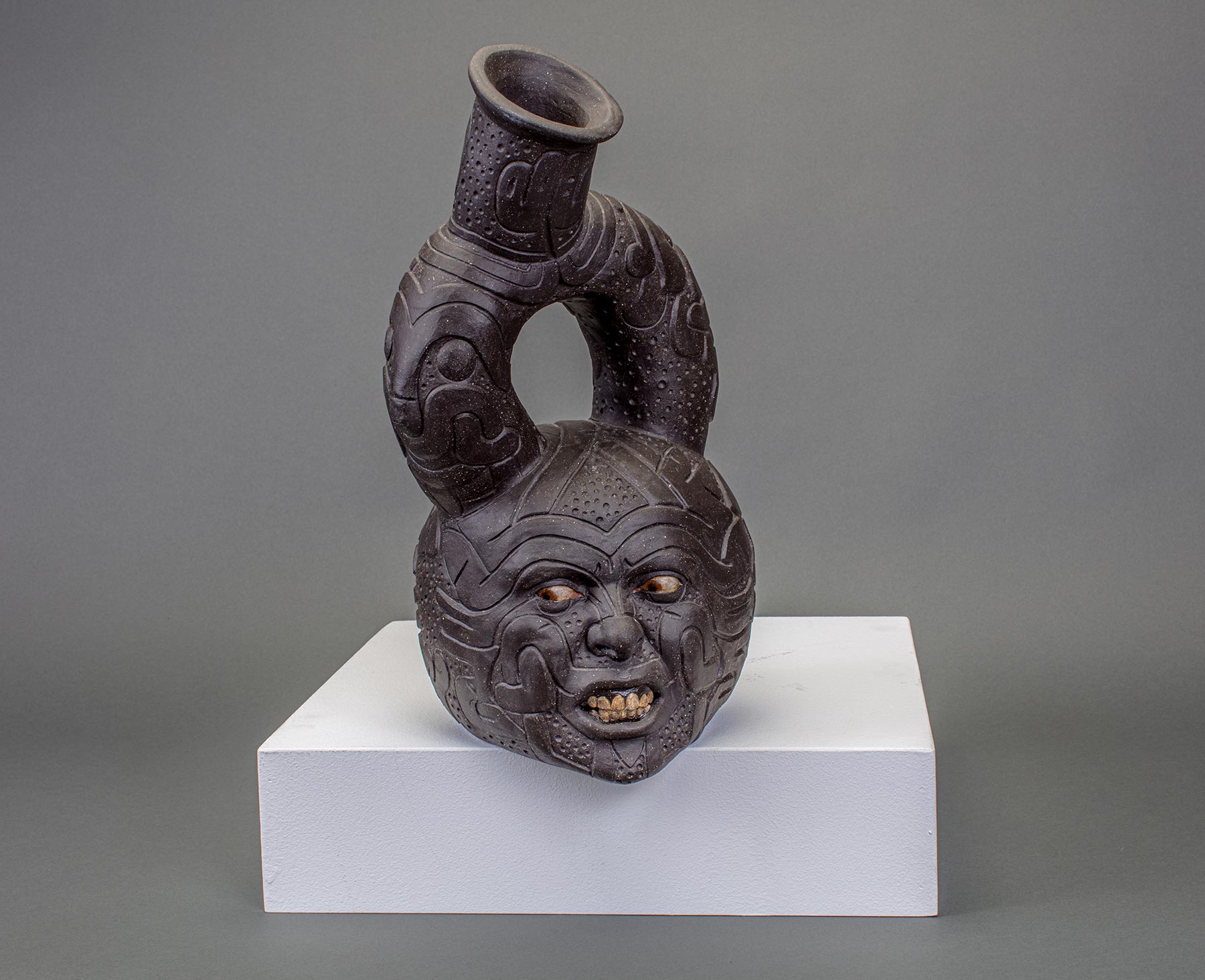

Gustavo Pérez

Sin Titulo (Untitled), 2003

Glazed stoneware

17 1/2 x 10 1/2 x 8 inches

Racine Art Museum, Gift of Frederick McBrien III

Photography: Jon Bolton

Pre-Hispanic art is part of my background…How it becomes a part of my work, I don’t know. Maybe it is in my subconscious. Things grow inside me. They have been growing for years. Maybe I had one idea when I was five years old and it took fifty years to come out. I think I have a huge cocktail of ‘influences,’ including architecture, dance, literature, music—all of these have influenced my work.

I don’t follow what’s going on in the world of ceramic. I’m not aware of trends. I’m friends with some other artists, but I work all the time…I don’t want to look at what other people are making. I don’t care about vacations. I crave time to work…My clay is my life.

Mexican ceramicist Gustavo Pérez first studied engineering at the Autonomous National University of Mexico, before attending the School of Art and Design in Mexico. The Veracruz native’s interest in mathematics is evident in his elegant vessels. Working only with stoneware, he creates works that are influenced by ancient Meso-American forms as well as minimalism. Pérez splits his time between his studio in Zoncuantla, Veracruz, Mexico, and the atelier of his partner, ceramicist Brigitte Pénicaud in Les Places, France.

Video courtesy of Museo del Palacio de Bellas Artes

Marva Lee Pitchford-Jolly

Sunday Baptism, 1985

Glazed earthenware

20 1/4 x 15 1/2 inches diameter

Racine Art Museum, Gift of Karen Johnson Boyd

Photography: Jon Bolton

[My] art is another permanent kind of thing to leave that says, “This is what I felt about black culture and how it contributed to the world.”

As a child, Marva Lee Pitchford-Jolly (1937–2012) would mold things from the mud found under the porch of her family home. Pitchford-Jolly pursued a career as a social worker but created ceramics off and on as a hobby. After she lost a job in healthcare due to funding cuts, she was able to dedicate herself to art full-time, and found art exhibition opportunities. One of these led to her being offered a part-time position teaching ceramics at Chicago State University. Pitchford-Jolly embraced this new role—often stating that she herself had to learn the technical aspects of ceramics at the same time as she was teaching her students.

Ever community-oriented, Pitchford-Jolly was involved in the South Side Community Art Center and Hyde Park Art Center in Chicago. She was a founder of the collective known as Sapphire and Crystals, an organization that encouraged female African American artists to create and exhibit together. As she gained popularity, she made a point to sell some of her work at affordable prices so it was accessible to a wider audience.

About her most well-known type of work, narrative vessels or “story pots,” Pitchford-Jolly stated:

I use clay as a canvas, and I taught myself to draw on clay…I could write my stories on these pots.

Maribel Portela

Caricios de Recuerdos I (Fond Memories I), 2004

Glazed earthenware

22 x 14 x 7 inches

Racine Art Museum, Gift of Karen Johnson Boyd

Photography: Jon Bolton

Maribel Portela, born and working in Mexico, blends nature, world views, and the relationship of human beings to the cosmos. Combining her interest in Mesoamerican civilizations and Buddhist hand gestures, Portela created a series of five large ceramic hands in 2004. About her work in general, which also incorporates paper, felt, bronze, and found natural materials, she states:

I am an artist who creates objects by manipulating common materials, situations, and recognizable imaginaries, my work contains elements of science and nature, also aspects that have to do with human beings, their desires, fears, dreams. I work creating tactile surfaces, which make a playful and provocative experience.

RAM has two large-scale ceramic hands by Portela in the collection—one was displayed in the 2021 Windows on Fifth Gallery exhibition, Playful/Pensive: Contemporary Artists and Contemporary Issues. The other piece could not be shown in the Windows gallery because it incorporates natural materials—specifically, seed pods that are sensitive to the heat and light of that particular gallery. This situation is a collection conservation issue—while technically the seed pods would be exposed to these things in their naturally occurring environment, the museum has to carefully consider any conditions that could alter work in the care of the collection.

Joyce Scott

Procreation (Neckpiece),1994

Glass beads, thread, and wire

11 1/4 x 11 5/8 x 1 3/4 inches

Racine Art Museum, Gift of Dale and Doug Anderson

Photography: Jon Bolton

It’s important to me to use art in a manner that incites people to look and then carry something home—even if it’s subliminal—that might make a change in them.

Perhaps best known for her beaded sculpture and adornment—though ultimately not bound by media—Joyce Scott does not shy away from addressing complex social, cultural, and political issues in her work. Scott’s heritage—she identifies African Americans, Native Americans, and Scots as ancestors—as well as her familial connections to quilters, basketweavers, story tellers, and other makers are cited as both resources and inspiration. Indeed, her quiltmaking mother not only taught her quilting techniques but also encouraged her to be an artist.

Named a MacArthur Fellow in 2016 and a Smithsonian Visionary Artist in 2019, Scott has been at the forefront of contemporary craft—pushing boundaries and upending expectations—for decades. Her beaded work is a combination of free-form and off-loom processes that allow her to create representational figures and narrative scenes. Procreation, one of several works by Scott in RAM’s collection, draws attention to the complex web of ideas associated with a woman’s body, fertility, and gender roles. An elaborate yet wearable neckpiece, this work is adornment with a message—the wearer becomes a collaborator with Scott or, in her words, a “walking billboard” for her thoughts.

Video courtesy of Craft in America

Yoko Sekino-Bové

Village Expert Teapot from the Genuine Fake China Series, 2010

Porcelain with lustres

Racine Art Museum, Gift of the Artist

Photography: Yoko Sekino-Bové

Yoko Sekino-Bové was born in Osaka, Japan. She graduated with a BFA in Graphic Design from Musashino Art University in Tokyo, Japan, and worked as a designer in Los Angeles before focusing on ceramics. She received an MFA in Ceramics form the University of Oklahoma. Her work has been featured in numerous publications and exhibitions.

RAM’s teapot and cups are a part of her Genuine Fake China Series. Of that series, she states:

This series is my quiet resistance against the current political situation in our time, of isolation and confrontation. Seems like we can use more of those reminders about how similar we are now than ever by exchanging stories and using small conversations, instead of abstract fear and anger. Many conflicts start with the fear of unknown, which can be reduced easily by getting know each other. If we learn the strangers eat like us, think like us, and live like us, I think we can relax a bit more.

Thus my Genuine Fake China series come with two sides: one with Chinese/Japanese proverb, another with English equivalent (or a saying that has the same nuance). It is my attempt to construct a bridge over the gap and start conversations about so many profound ideas we share even in different periods, languages and cultures. While learning American English, I discovered that proverbs are an essence of the culture/language the people use, a condensed reflection of their philosophy. If there is a proverb in two languages that shares the same idea, I can comfortably say those two group of people think alike, at least on the specific subject. If the saying exists in multiple cultures, it would be a great proof that it’s a universal idea.

Preston Singletary

Totem Vase, 1997

Glass

16 7/8 x 5 7/8 inches diameter

Racine Art Museum, Gift of Devra Breslow

Photography: Jon Bolton

Through teaching and collaborating in glass with other Native American, Maori, Hawaiian, and Australian Aboriginal artists, I’ve come to see that glass brings another dimension to indigenous art. The artistic perspective of indigenous people reflects a unique and vital visual language which has connections to the ancient codes and symbols of the land, and this interaction has informed and inspired my own work.

Blending historical European glass-blowing traditions and Tlinglit design, Preston Singletary offers nuanced, sensitive, and compelling blown-glass forms as well as large-scale commissions and more expansive projects. Exploring themes of transformation and the natural world in addition to personal and cultural beliefs, Singletary expands the possibilities of glass as a sculptural and narrative material. With work in major collections, including RAM’s, he is a dynamic presence in contemporary glass, maintaining an active teaching, lecturing, and exhibiting schedule that he balances with studio production time.

Art Smith

Purity Ring, ca. 1975

14k-gold and rose quartz

1 3/16 x 7/8 x1/2 inches

Racine Art Museum, Gift of Karen Johnson Boyd

Photography: Jon Bolton

Music lover and member of the Duke Ellington Society at the time of his death, Art Smith (1917–1982) blended musical inspiration with artistic inspiration throughout his career as an art jeweler. Born in Cuba to Jamaican parents, Smith moved with his family to Brooklyn when he was three years old. While he studied sculpture formally, he gravitated toward jewelry-making and opened a shop in New York in 1946.

Two points about his jewelry design are often repeated. He favored “biomorphic abstraction” with his organic somewhat free-flowing designs and he created jewelry with the form of the body in mind—like a bracelet that becomes a cuff, following and extending the lines of a wrist and arm. Even when a piece is large, it is likely lightweight and very wearable. It is significant that he created work that sold to a variety of clientele and accepted commissions for musicians and others, such as the Peekskill Chapter of the NAACP. He also worked with several African-American dance companies, creating stage jewelry for the dancers.

Smith gained his reputation and grew his business, but not without discrimination. He moved his first shop due to racial tension in that particular area of Greenwich Village, New York. Smith has been described as a political activist, “similar to his parents,” and supported racial and sexual equality.

Video courtesy of Craft in America

Kevin Snipes

Hooz Yer Mammy, 2012

Glazed porcelain

9 x 2 1/2 x 4 inches

Racine Art Museum, Gift of David and Jacqueline Charak

Photography: Jon Bolton

Kevin Snipes combines his love of creating unconventional pottery with a desire to draw on everything that he makes. As an African-American ceramic artist, Snipes notes that people often expect black figures to populate his work. To deal with this expectation on his own terms, he investigates the concepts of duality and otherness, using the multiple sides of his pieces as metaphors for differing perspectives. About this aspect of his work, Snipes states:

The stories I tell are open-ended investigations of difference and otherness. They are ways in which I can explore the underlying emotional and psychological issues of discrimination. I am interested in what happens when people who are different come together. One aspect of my work is that the narratives I portray encompass different sides, so that every side of the piece is the front side, or protagonist.

Snipes received a BFA in ceramics and drawing from the Cleveland Institute of Art, Ohio, in 1994 and an MFA in ceramics at the University of Florida, Gainesville, in 2013. He has exhibited throughout the US and internationally.

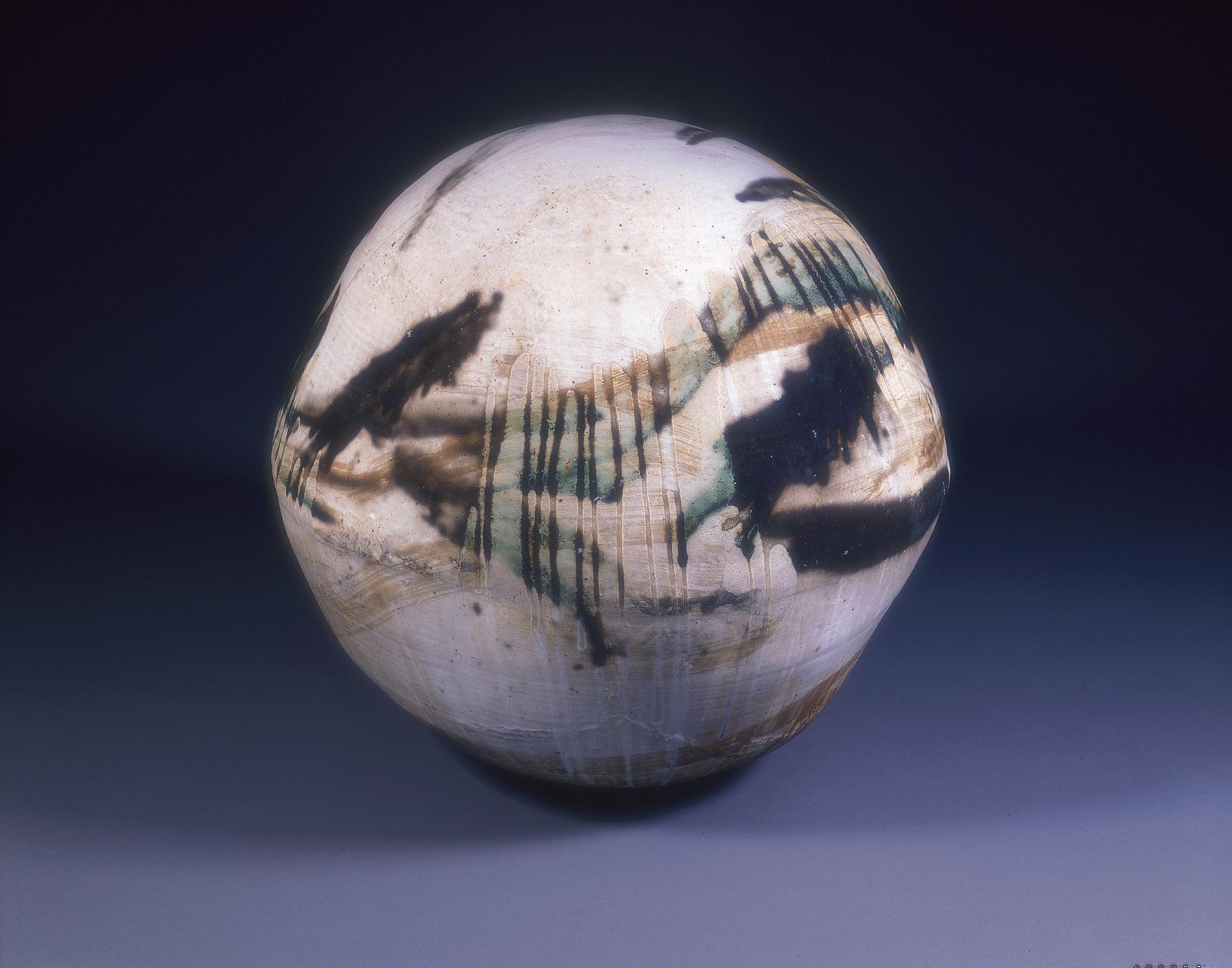

Toshiko Takaezu

Mondo, 1989

Glazed stoneware

26 x 25 inches diameter

Racine Art Museum, Gift of the Artist and Karen Johnson Boyd in Memory of Samuel C. Johnson

Photography: Michael Tropea

You are not an artist simply because you paint or sculpt or make pots that cannot be used. An artist is a poet in his or her own medium. And when an artist produces a good piece, that work has mystery, an unsaid quality; it is alive

Boundary-breaking and extremely influential, Toshiko Takaezu (1922–2011) set a new standard for what clay could do as a material and as an idea. RAM became a favorite place for the artist and, ultimately, the repository of more than 30 works created throughout her career, including her largest and most significant installation, the Star Series. Takaezu’s legacy encompasses not only her work but also her willingness to share her wisdom. Her studio, and, really, anywhere she was, became a place of inspiration.

Akio Takamori

Young Men with a Woman, 1993

Glazed porcelain

Racine Art Museum, Gift of Gail M. and Robert A. Brown

Photography: Jon Bolton

Noted Japanese ceramic sculptor Akio Takamori (1950–2017) created work that addresses relationships and the human body depicted through everyday people, historical characters, animals, mythological figures, and unidentified lovers. While Takamori sometimes rooted his forms in the concept of functional work, such as teapots or bowls, he also created freestanding figurative work of individuals or vessel shapes with interrelated figures. Takamori was very familiar with Western historical painting while being directly influenced by Japanese erotic woodcuts as well. He combined that knowledge with an awareness of human anatomy learned during a childhood spent around his father’s medical practice. There, he encountered patients suffering with venereal disease or the effects of nuclear bombing and nurses who told stories that blended human bodies with supernatural powers.

Video courtesy of Craft in America

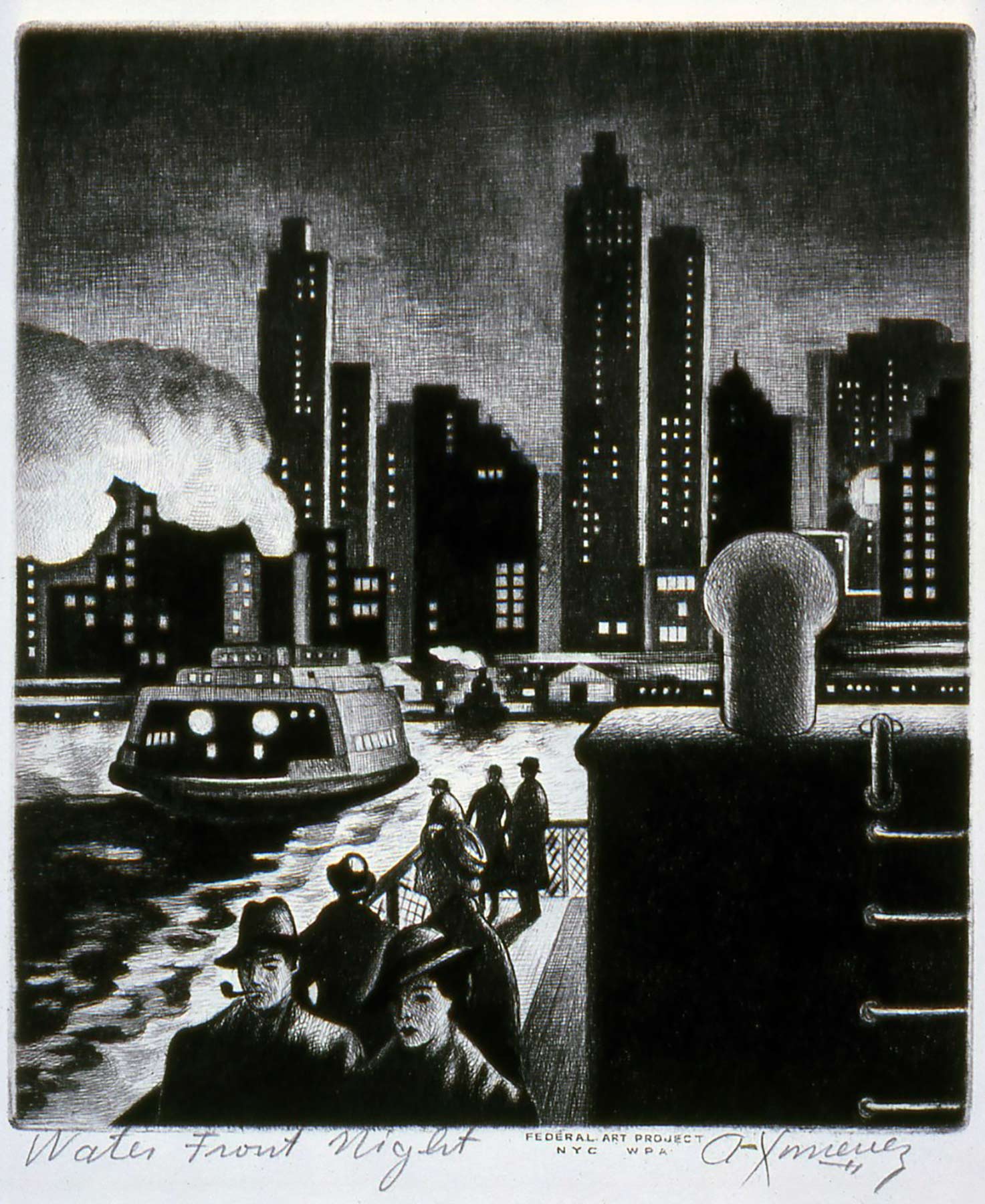

Rufino Tamayo

Wood Choppers, 1937

Watercolor

10 7/8 x 8 1/4 inches

Racine Art Museum, Work Progress Administration, New York Federal Art Project

Photography: Jon Bolton

Rufino Tamayo (1899–1991) was born in Oaxaca, Mexico. Through paintings, sculptures, and prints, Tamayo depicted subjects that reflected his Mexican heritage and pride, knowledge of European art, and response to indigenous art and objects. While he was applauded for bringing attention to Mexican art in the twentieth century and was a strong proponent of exploring Mexican-oriented themes in his work, his political stance was different from that of popular Mexican muralists Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco, and David Alfaro Siqueiros. In Tamayo’s work, this came across as a search for the “true essence of Mexicanness,” as he favored more abstract representations and incorporated European influences of Cubism and Surrealism.

Tamayo had extended stays in New York, New York on more than one occasion. Living there for a period of time after the Great Depression of the 1930s, he had the opportunity to produce artwork under the support of the Federal Works Progress Administration (WPA). It is documented that he produced an “easel painting” every month for a fee. Tamayo’s watercolor in RAM’s collection is one of the works he created through the WPA. Identified as “wood choppers,” the subjects are anonymous otherwise, rendered in Tamayo’s maturing style. The hat and clothes of the workers reflect his noted connections to Mexican subject matter and directly correspond to other pieces he created with this theme in mind. Interestingly, many of the artists working with the WPA, regardless of their heritage, depicted everyday life including people at work.

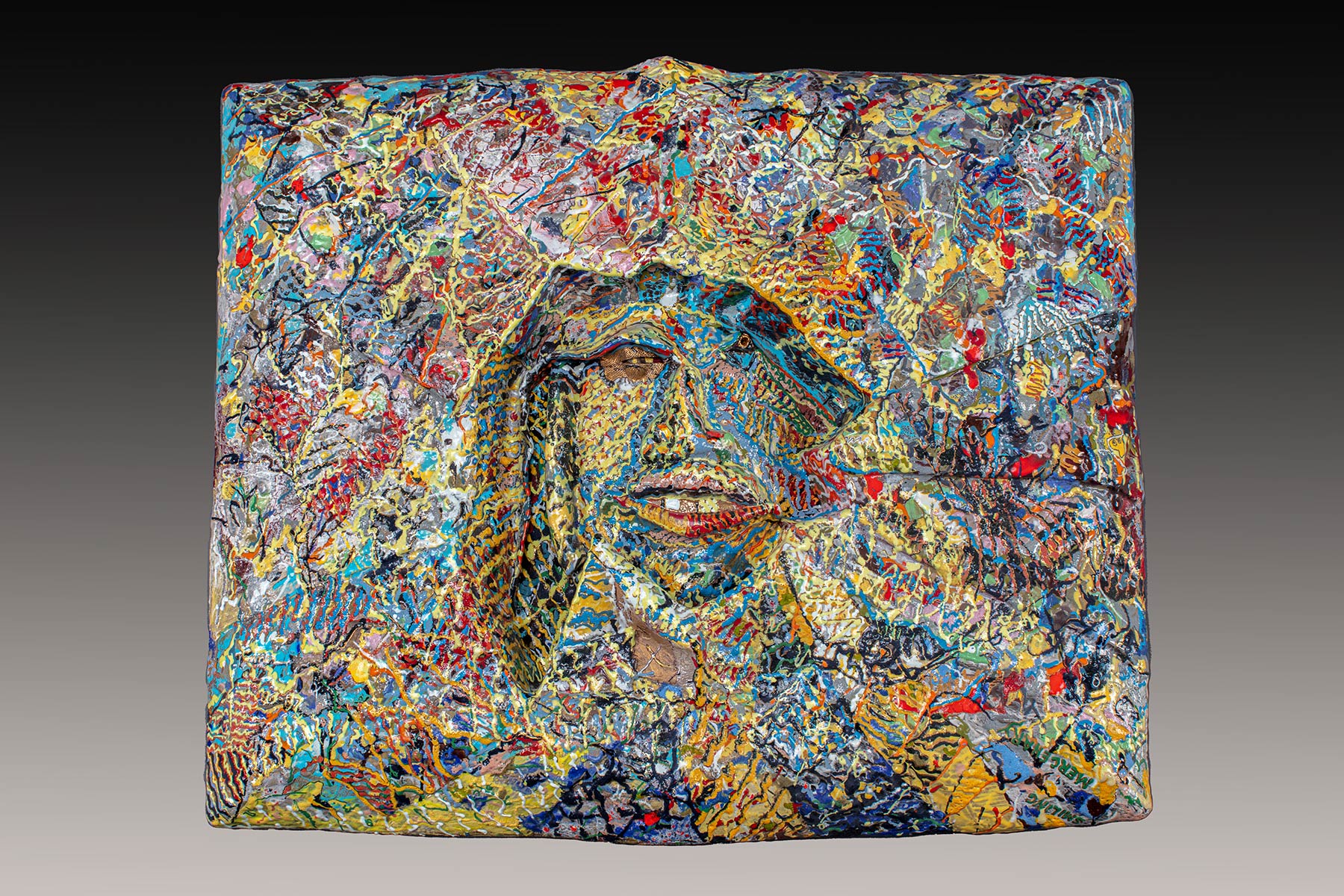

James Tanner

Smiling Mercenary, 1987

Glazed earthenware

25 x 31 1/2 x 5 inches

Racine Art Museum, Gift of Karen Johnson Boyd

Photography: Jon Bolton

James Tanner, professor emeritus of ceramics at Minnesota State University at Mankato, has used many materials in his artistic explorations. While his works employing clay are probably his best known, he has also created paintings, prints, and works of glass in addition to experimenting with various other media.

Tanner was interviewed in 2011 about his life and work for an oral history archive at the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. While many topics are addressed, Tanner’s explanation of his process with clay is particularly illuminating.

He stated:

My clay has some paper pulp, and that helps with distribution of water drying and helps make it a little thinner—I mean, a little lighter…I make the slabs as thin as I can and still maintain structural integrity…I build vertical structures that are kind of like trusses. Then some of those are covered in developing the imagery. It ends up being cellular and kind of segmented in terms of that structure.

I fire intermittently so that it’s hardened and I add things to my ceramic chemicals to make that stick to the clay. I also thicken up the application by taking the water out. I use a lot of low-fire chemicals that are commercial. I mix some things myself. But this allows me to take the water off and get a very—just a heavy viscosity out of the material. I can actually extrude the material. Through a syringe, I can throw it on the surface. I have several methods of doing that. We use the palette and my paintbrush. I actually use some powdered metals…And this stuff is fired over and over until I reach a point of satisfaction, I guess I would call it, where the piece has—I guess it exudes a kind of life force.

That’s how I look at work, actually, when it is ready to be released, it’s done, so people call it done. But everything’s in flux and it’s continuous. You move from one piece to the next, which is the same piece in my notion. It’s like it carries over some of the history. Development has a lot to do with keeping the—what should I say—keeping the sewers open, not allowing ego to be omnipotent, and realizing that the materials, you, the process, the tools are all orchestrated to be in harmony in some kind of way, and that it doesn’t depend on any one aspect but all of them. It’s a cooperative, participatory act.

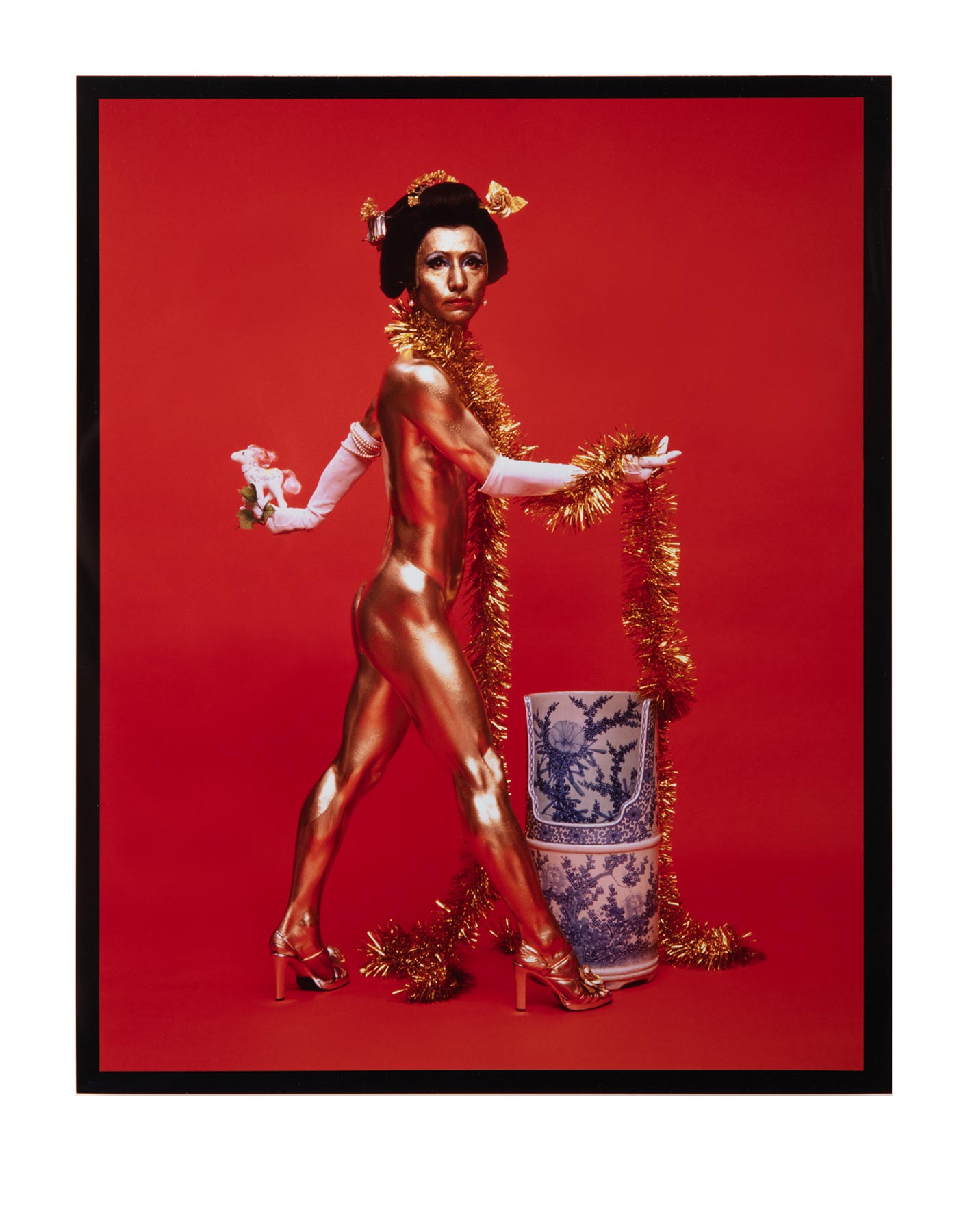

Masami Teraoka

Namiyo at Hanauma Bay, 1985

Color lithograph, edition 91/150

25 x 34 inches

Racine Art Museum, Gift of Karen Johnson Boyd

Photography: Jon Bolton

The devastation Masami Teraoka saw in his early years—when he survived the nuclear bombing of Hiroshima, Japan in 1945—has not been a part of all of his work but the impact and—not always metaphorical—collision of the so-called East and West has. Teraoka has lived in the United States since 1961, absorbing popular culture and making work that both reflects his heritage and satirizes modern society, often combining seemingly disparate images such as geisha and McDonald’s hamburgers.

A painter and printmaker, Teraoka was influenced by personal experiences as well as cultural observations including Western painters like Paul Cezanne and Japanese artists like Hokusai. In fact, Hokusai’s famous print, The Great Wave Off Kanagawa seems like direct inspiration for the Wave Series that Teraoka completed in the 1980s. In RAM’s collection, Teraoka’s print, Namiyo at Hanauma Bay, features an ocean swimmer surrounded by gigantic waves. The aesthetic echoes Hokusai and the Japanese text included in the corners suggests historical precedents but the snorkel mask in the swimmer’s hands upends the narrative and lends a more contemporary tone.

Cynthia Toops

Brooch, 2001

Polymer and sterling silver

3 x 1 1/2 x 1/4 inches

Racine Art Museum, Gift of Trish Rodimer

Photography: Jon Bolton

A pioneer in polymer art, Cynthia Toops has been pushing the boundaries of the medium since the 1980s. Born in Hong Kong, Toops—like other polymer artists—found her way to polymer after first pursuing other interests. Previously, she obtained a BA in Biology from Drake University, Des Moines, Iowa, and a BFA in Printmaking from the University of Washington, Seattle, Washington.

Inspired by, in her words, “mundane” events or objects, botanical subjects, and the ethnic jewelry and ancient beads she and her husband collect, Toops is drawn to detail and labor intensive techniques. While she has recently been working with thin sheets of polymer, she is well-known for mircromosaic works, such as the brooch pictured from RAM’s collection. To create this type of work, she pieces together tiny shards of polymer into figurative or abstract imagery.

While Toops works on her own, she also often collaborates with her husband, Dan Adams, who creates glass works, and Chuck Domitrovich, a metalsmith. To date, RAM is fortunate to have ten works by Toops—including one collaboration with Adams—in the collection.

Dorothy Torivio

Vessel, 1981

Glazed earthenware

1 x 2 1/4 inches diameter

Racine Art Museum, Gift of Karen Johnson Boyd

Photography: Jon Bolton

My brain is my computer.

Acoma potter Dorothy Torivio (1946–2011) gained recognition for eye-dazzling, high contrast designs on ceramic pots, vessels, bowls, and figures. Torivio’s working process included formulating a pattern in her head before applying her brush to an object’s surface. She established her own style with particularly complex patterns that take advantage of the optical play of positive and negative space. The quote above is the artist’s response when a mathematics professor told her it took him a long time to work out her designs on his computer.

While her aesthetic is innovative, Torivio followed some Pueblo traditions as a member of a network of women in her family who make pottery, build ceramic forms by hand—specifically through coiling—and fire pieces in pit kilns outdoors. Garnering numerous awards, Torivio drew attention for the way she blended tradition and experimentation. Her work was featured in numerous exhibitions, and she ultimately traveled across the US, demonstrating her process and teaching.

RAM currently has two works by Torivio in the collection—each exemplifying the elaborate designs that became her hallmark. These works, along with others made by various Pueblo potters, reflect RAM’s desire to share diverse voices in contemporary craft.

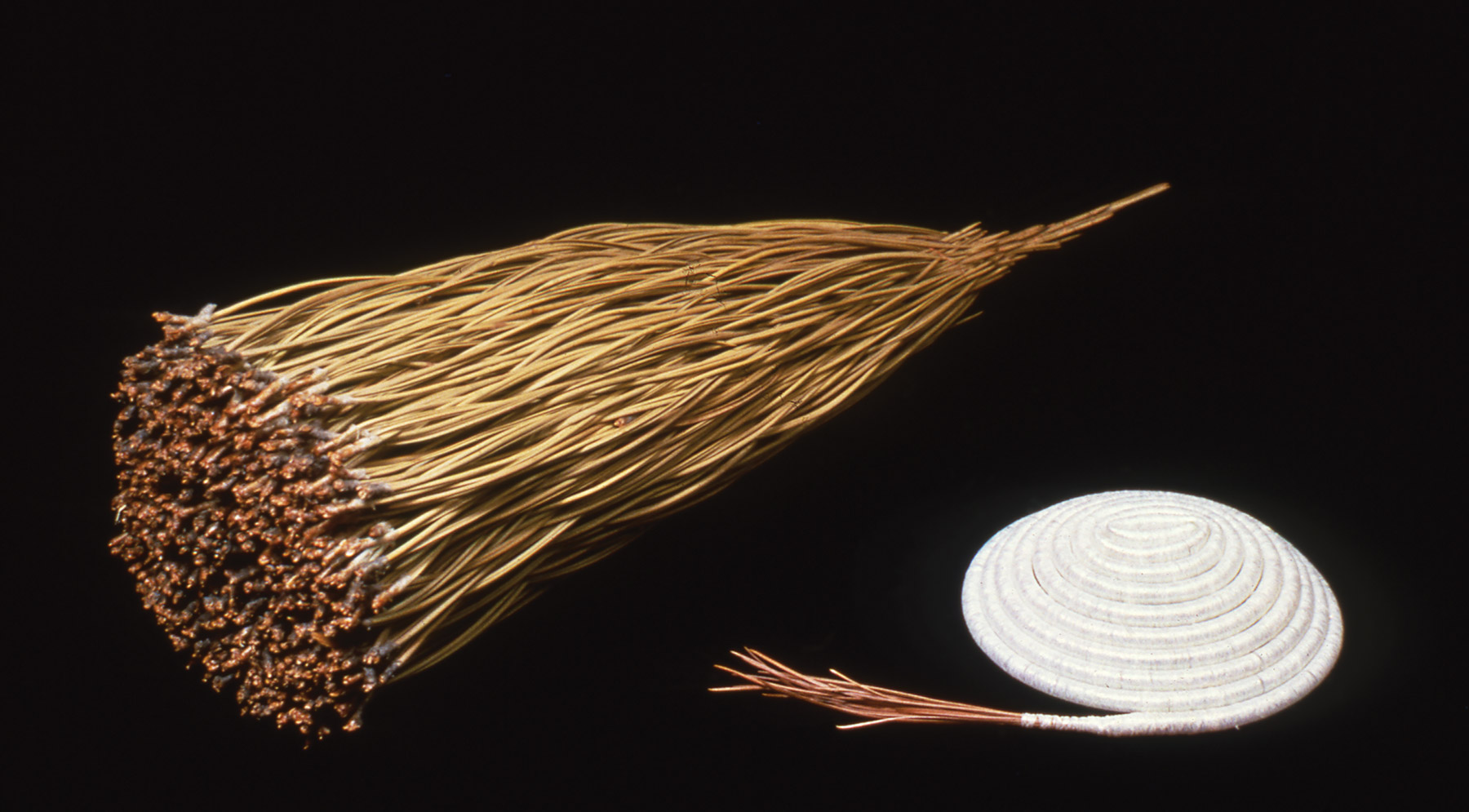

Dawn Walden

Random Order Anishnaabe, ca. 2005

Cedar bark and cedar root

51 x 23 x 23 inches

Racine Art Museum, Gift of Danielle and Norman Bodine

Photography: Jon Bolton

The maker becomes infused with the materials, and then the materials make the basket.

As an Ojibwe descendant and member of the Mackinac Band of Chippewa and Ottawa Indians, Dawn Walden fuses her creative spirit with the study of ethnobotany to create sculptural baskets. Born in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, Walden studied art at Ferris University and worked for the Department of Defense for several years. Her interest in the relationship between nature, culture, and spiritual beliefs—especially of the Ojibwe—led her to explore basketry techniques and materials. Ultimately, she has developed a practice linking material and labor’s significance with cultural and natural history. Significantly, Walden’s training in basketry and ethnobotany has been informal, rooted in workshops and investigations led by elders and artists of different native cultures in the Northwest.

RAM currently has one work by Walden in the collection: a cedar bark and cedar root basket titled Random Order Anishnaabe. The lip of the basket—only visible to those tall enough to see the top, around four feet tall—is comprised of linked figures also made of cedar. Anishnaabe refers to a group of related Indigenous peoples—of which Ojibwe is one—in the Great Lakes region of Canada and the United States.

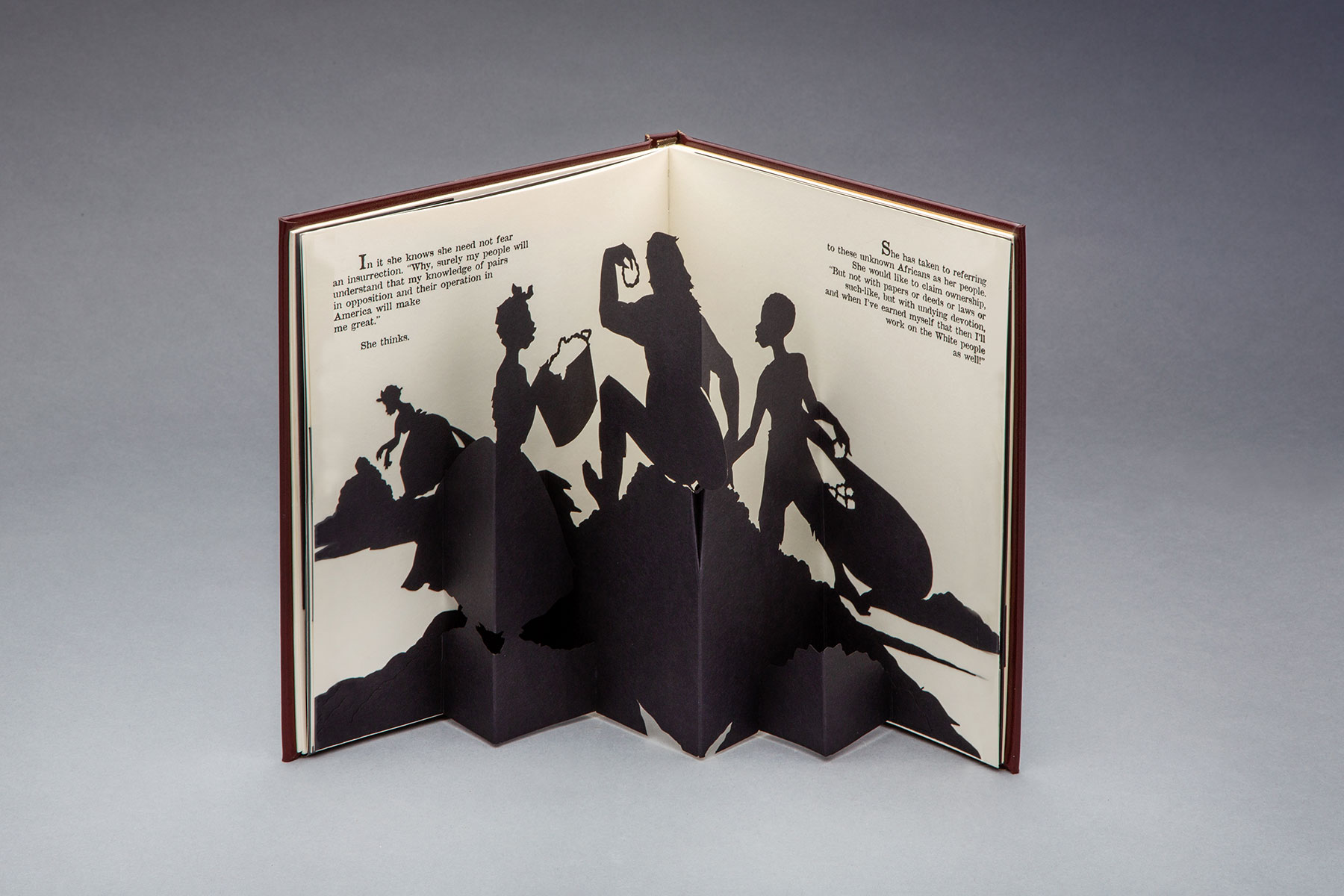

Kara Walker

Freedom: A Fable—A Curious Interpretation of the Wit of a Negress in Troubled Times, 1997

Offset lithograph, dyed leather, and laser-cut paper, Artists’ book, edition of 4,000

9 1/4 x 8 3/8 inches

Racine Art Museum, Gift of Peter and Eileen Norton and Family

Photography: Jon Bolton

I’m not really about blackness, per se, but about blackness and whiteness, and what they mean and how they interact with one another and what power is all about…Challenging and highlighting abusive power dynamics in our culture is my goal; replicating them is not.

First known for large-scale tableaux of cut paper silhouettes, Kara Walker has utilized a broad range of media in her practice including silhouettes, prints, film, video, and installations. Walker’s thought-provoking investigations of race, sexuality, history, gender, and identity engage on many levels. Often playing off of stereotypes and the misconceptions they can lead to, Walker has—by design—encouraged a wide range of responses from a wide range of viewers. As she states:

I didn’t want a completely passive viewer. Art means too much to me. To be able to articulate something visually is really an important thing,…I wanted to make work where the viewer wouldn’t walk away…

Walker’s book, ultimately a pop-up with its dimensional pages, crosses media boundaries in RAM’s collection as a work on paper, an artists’ book, and an object. Her piece also subverts expectations in that it combines a popular children’s book format with a complex, layered narrative. This kind of work, which operates in between categories, can be pivotal in encouraging conversations about assumptions and relationships, where compositional choices become metaphors for society. While her installations and larger works envelop visitors, this book pulls viewers into a smaller, more intimate—yet no less powerful—space. From there, Walker offers a narrative about freedom through the eyes of a female slave.

Kara Walker received a BFA from the Atlanta College of Art and an MFA from the Rhode Island School of Design, Providence, Rhode Island. Currently the Tepper Chair in Visual Arts at the Mason Gross School of the Arts at Rutgers University, New Brunswick, New Jersey, her work has been exhibited extensively and can be found in museums and public collections internationally. Walker is the recipient of many awards, including the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation Achievement Award.

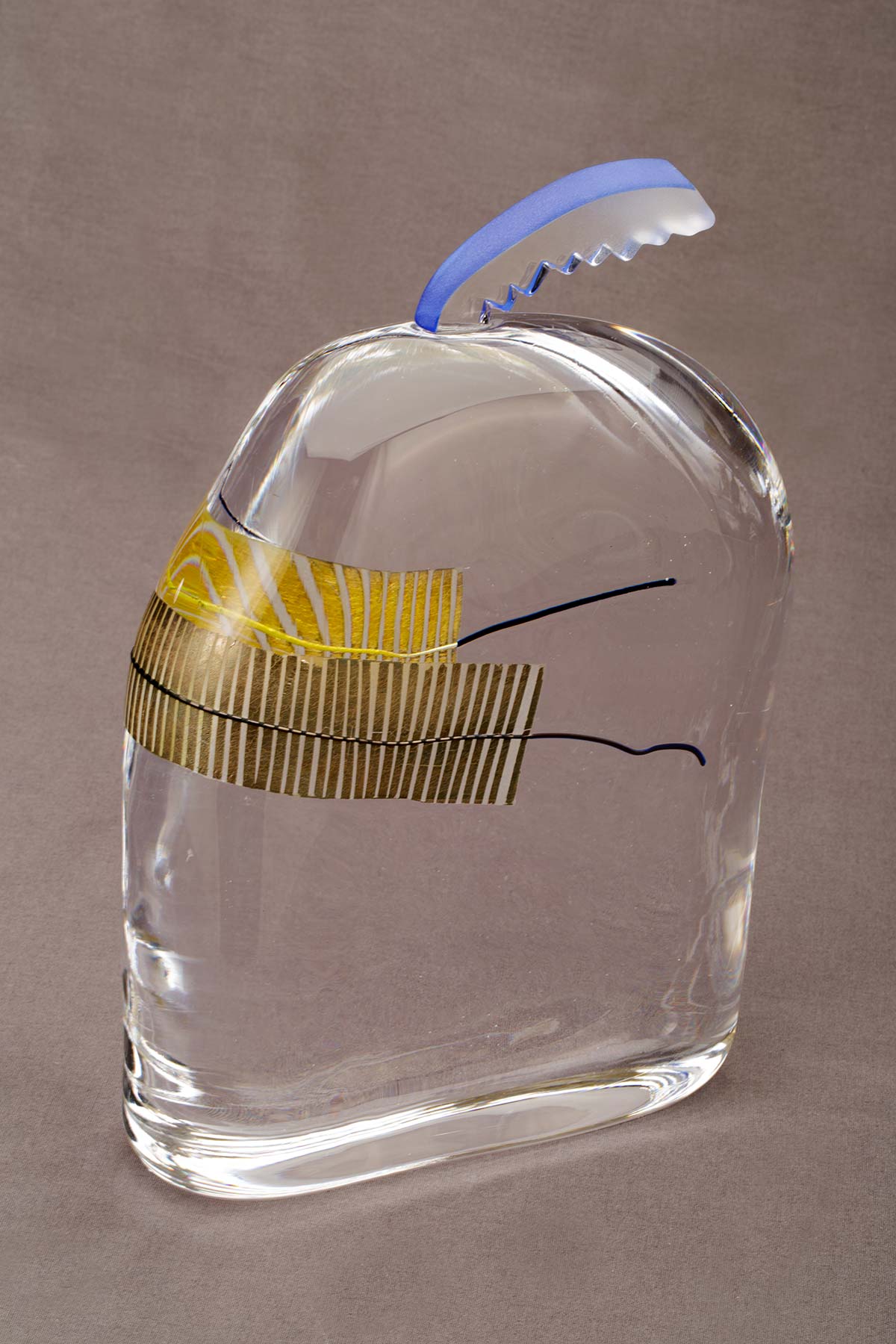

Brent Kee Young

Double Trouble from the Fossil Series, 1981

Glass and copper

8 x 5 1/2 inches diameter

Racine Art Museum, Gift of Michael L. and Anne Webber Brody in honor of Judith and Stanton Brody

Photography: Jon Bolton

My work speaks of many things… of a respect for things natural; of ambiguity in space, form, volume, time, and images that are not there. It speaks of… man’s marks, nature’s marks, and their relation [to one another].

Brent Kee Young’s career has been filled with experimentation and innovation fueled by a “fascination with the process of handling hot glass.” Young, the son of noted Chinese American actor Victor Sen Yung, began studying engineering, switched to ceramics, then was ultimately accepted into a master’s program at San Jose State University based on his work in glass. His career has been marked by technical achievements and his desire to use various techniques.

RAM currently has five works by Young in the collection, including multiple pieces from his Fossil Series. With this series, he explored the notion of ambiguity—tapping into the idea that fossils are not the things that existed but impressions of things that existed. He incorporated mold-making techniques—developing a clay model of his desired piece and then using it as a mold—as well as flameworking. For his current work—in which he builds networks of clear glass into various shapes—Young drew upon the flameworking processes that he employed with the early Fossil Series.

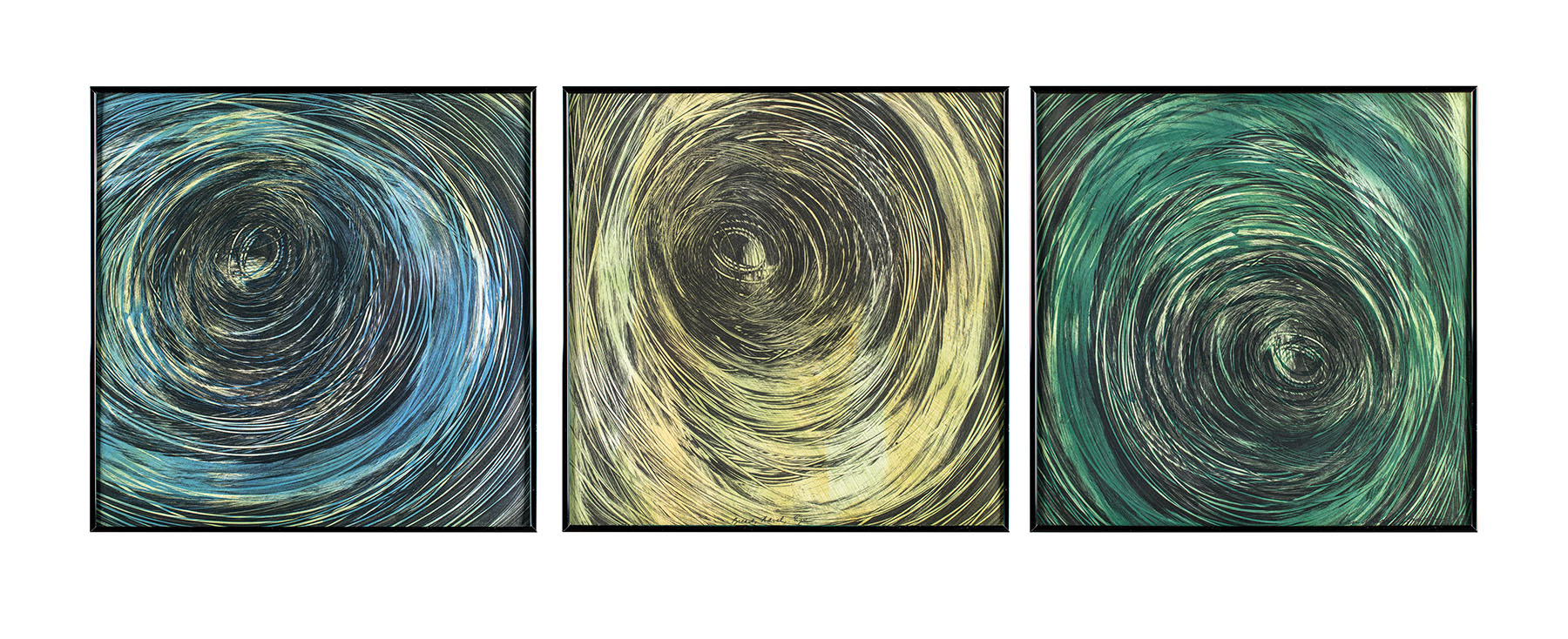

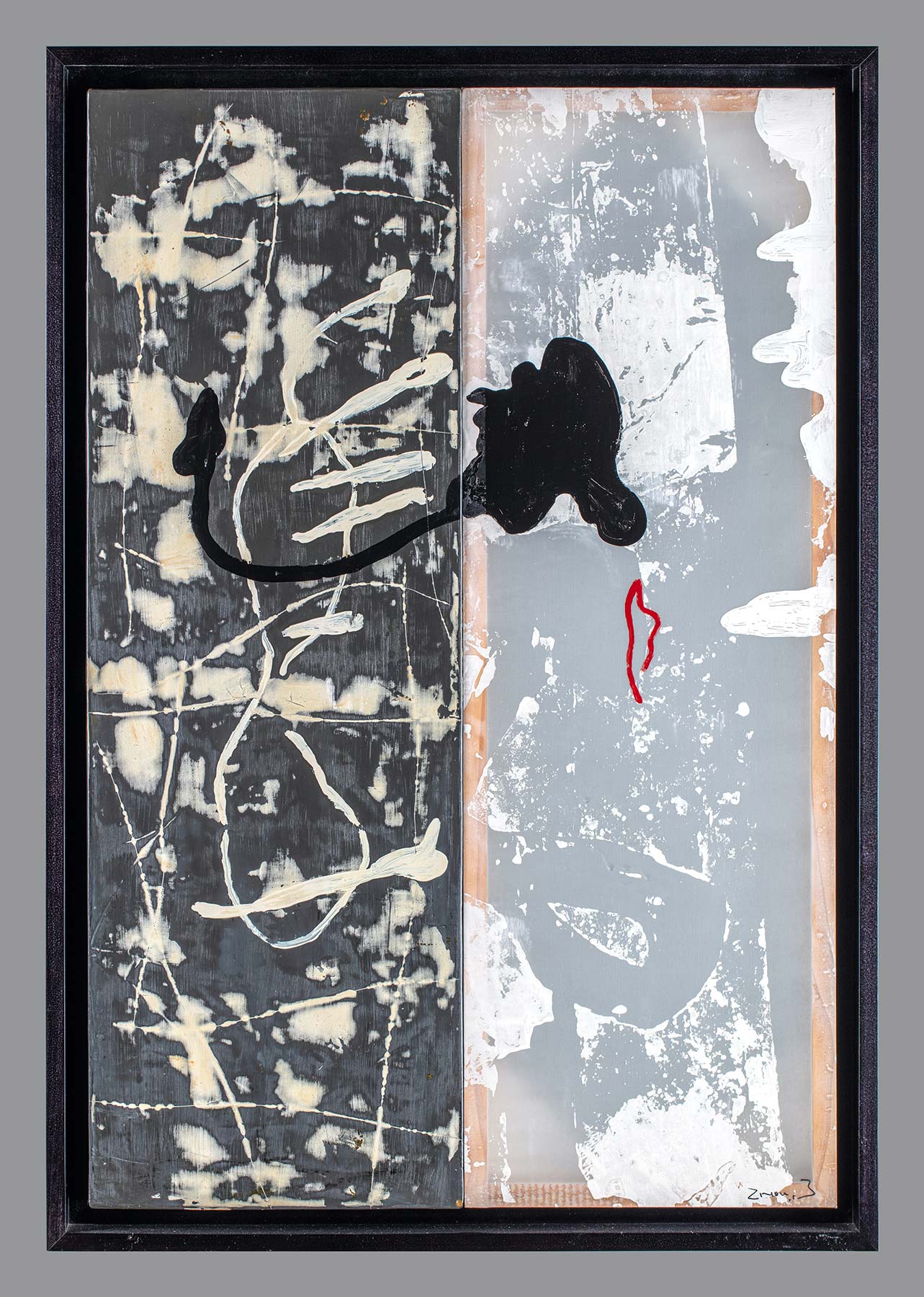

ShanZou and DaHuang Zhou

BZ 1382 or Waterlily #15, 2001

Oil on lead and silk

36 1/4 x 24 inches

Racine Art Museum, Gift of Karen Johnson Boyd

Photography: Jon Bolton

Not limited by media, the Zhou Brothers—Shan Zuo and Da Huang—experiment with various modes of creative expression, including painting, performance, and sculpture. Their works combine their unique perspective and aesthetic with creative interpretations of western and eastern philosophy, art, and literature. After originally becoming successful in China, the brothers moved to Chicago to continue their art careers in the US.

With their collaborative working process, the Zhou Brothers challenge the concept of the individual artist as a solitary self-focused genius. About this way of working, Da Huang has stated:

The value of the collaboration is that it opens up things that couldn’t happen any other way. When you paint by yourself, no matter how great a painter you are… you won’t have the courage to destroy your own painting. You think you are always right. But two people together, they don’t care. You paint something amazing, but he destroys it, because he sees it differently. And with this kind of fighting, something comes out in the painting that’s never happened before. It’s a mystery, and it creates a new magic…At the beginning, we knew it was interesting, but we didn’t know how special it was… But more and more as we worked together, we realized the value of the collaboration. People think we have the same idea and bring harmony to it before coming to the canvas. That’s wrong. The value of the collaboration is that it opens up things that couldn’t happen any other way.

More Work from RAM’s Collection by Artists of Color

Click/tap an image for more information

Stay in Touch

The Racine Art Museum and RAM’s Wustum Museum work together to serve as a community resource, with spaces for discovery, creation, and connection. Keep up to date on everything happening at both museum campuses—and beyond—by subscribing to our email newsletter: