Women Artists at RAM

RAM acknowledges the efforts of self-identifying women in the art world consistently and sincerely at all times. The museum highlights how women are inextricably woven—and often the foundation—of creative endeavors and discourse. By current count, 41% of the artists in RAM’s collection are women. This percentage—which is consistently increasing—is already substantially greater than the ratios calculated at other organizations with permanent collections and active exhibition programs. At RAM, work made by different genders is considered for inclusion in the museum’s holdings on equal terms. And notably, because RAM relies on gifts of artwork to build the collection, this policy has been reinforced by open-minded donors who have collected, and then donated, quality work regardless of the gender of the artist.

This portfolio highlights the work of women artists in RAM’s collection. It is not exhaustive and will be built upon over time as more documentation of women represented in the collection grows. This effort—similar to efforts to highlight artists of color at RAM—is not meant to single out artists to stigmatize them but to magnify and cast a spotlight on their significance. It reflects intention, goodwill, and an attempt to reckon with years of historical underrepresentation. The museum hopes that this provides opportunities for audiences to learn more about these artists and their ideas.

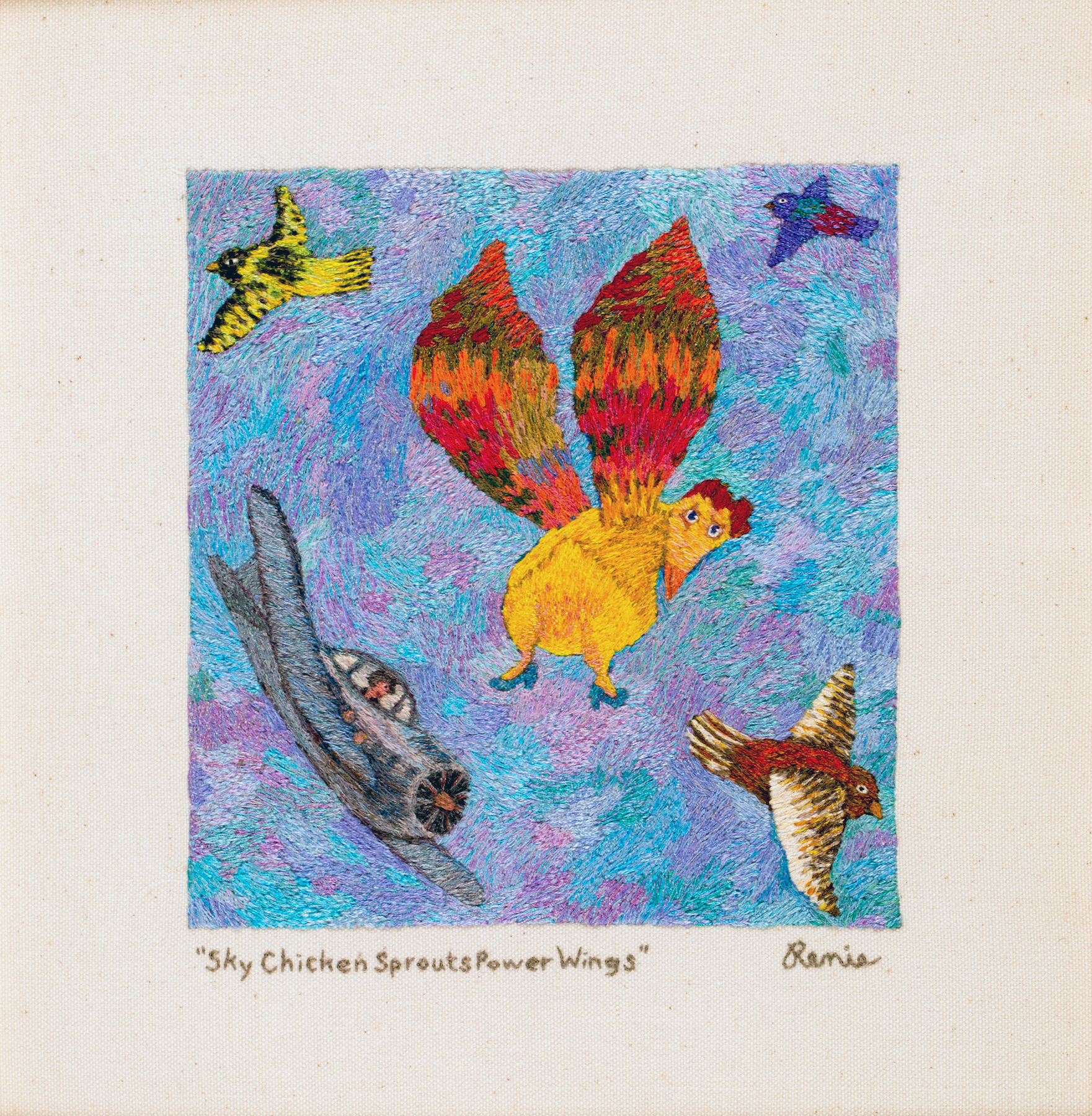

Renie Breskin Adams

Sky Chicken Sprouts Power Wings, 2001

Dyed cotton thread and fabric

7 1/8 x 6 1/8 inches

Racine Art Museum, Gift of the Artist

Photography: Jon Bolton

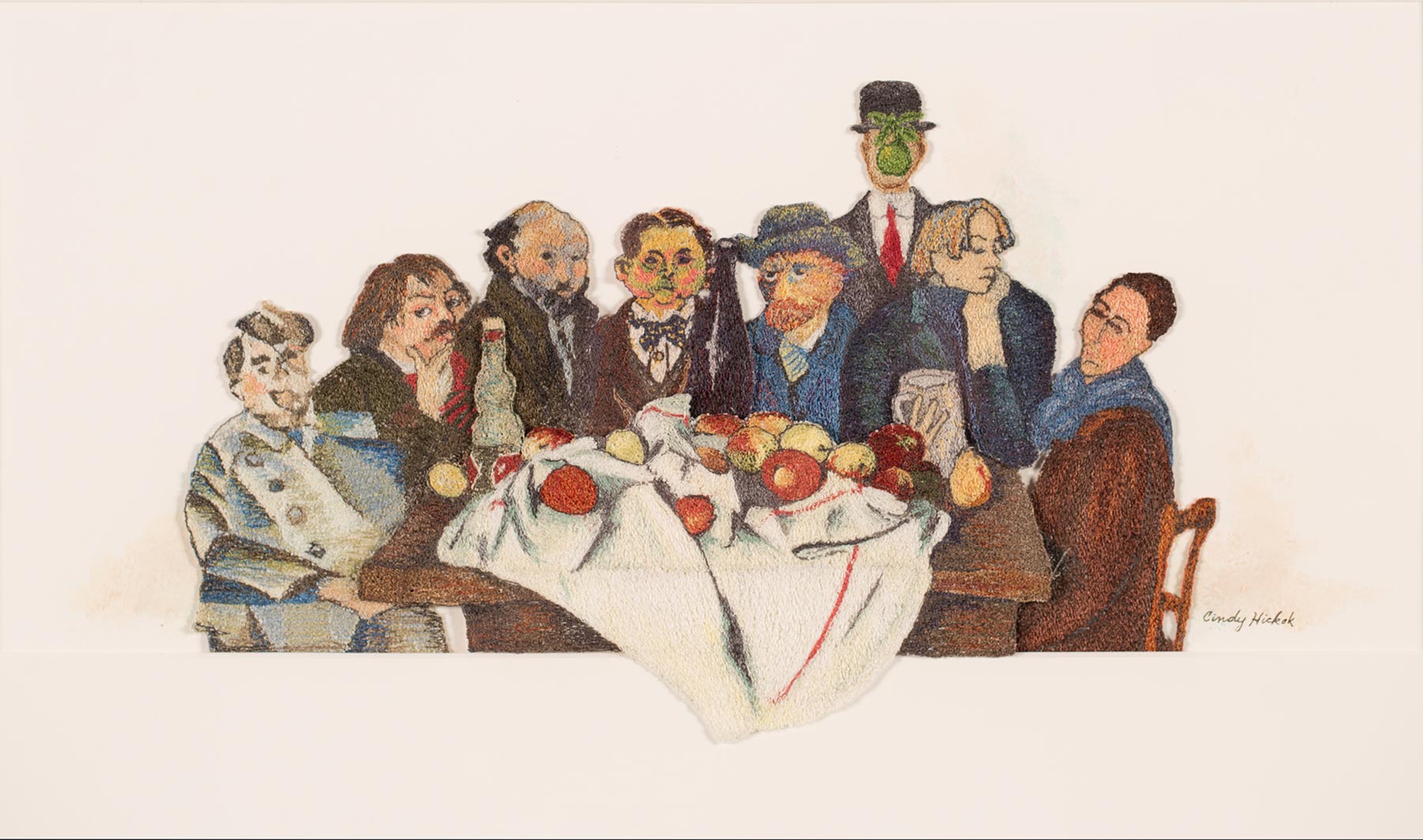

In the 1970s, I was lucky to find a first teaching position in home economics at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. While many women were engaged in overt political action, I was engaged in the struggles of being liberated. I loved teaching and helped women (and a few men) find the authority within themselves. My work in general communicates a woman’s intuitiveness and sensibility.

With degrees in psychology, anthropology, and visual arts, Renie Breskin Adams brings marked thoughtfulness and sensitivity to what she calls her “embroidered pictures.” Adams draws on things she has experienced, thought, felt, and imagined—translating them into colorful two-dimensional works that combine embroidery with knotless netting, weaving, crocheting, knotting, and—on occasion—paint or ink. Over the last 20 years, RAM has acquired over 80 works by Adams, establishing an archive and making RAM the largest single repository of her work.

As a child, Adams sewed, crocheted afghans, and made rag dolls. As a student in her twenties, she first studied drawing and painting while a research associate in psychology and education. A weaving class offered her the opportunity to explore composition and style in a way that drawing and painting did not. Over time, Adams has made a habit of experimenting with different techniques and merges methods as needed.

Kate Anderson

Jasper John’s Teapot, ca. 2000

Dyed linen, wood, and paint

10 x 10 1/2 x 3 inches

Racine Art Museum, Gift of David and Jacqueline Charak

Photography: Jon Bolton

Kate Anderson references art history and popular culture with her knotted non-functional teapots. Their subjects have included Marilyn Monroe as depicted on a magazine cover and works by American artists Georgia O’Keefe, Roy Lichtenstein, and Andy Warhol. Anderson encourages a reconsideration of historic images by placing them in a new context. In her words, she engages in “reinterpreting the experience of how we are meant to perceive a snapshot of American history.”

Anderson’s Jasper Johns Teapot is layered with meaning. The famous American painter and printmaker Jasper Johns first began to use flags and target signs in his work in the 1950s—a time when targets were strongly associated with military and firearms. In the context of visual art, a target could also be associated with being seen—the focus of someone’s looking or inquiry. Johns was, at the time, keeping his homosexuality quiet. Did his use of targets have more personal meaning?

The flag as rendered by Johns was, in his words, a response to things that were “seen but also not seen.” His first flag was painted in encaustic so that it retained brushstrokes rather than looking crisp and clean. The 48 stars of Anderson’s flag rendering reflects the US flag at the time of the original Johns’ painting since that was the number of stars, and US states, from 1912 to 1959. In choosing Johns and some of his most iconic works as subjects for her work, Anderson indirectly sets the stage for further questions.

Amy E. Arntson

Peninsula Point Morning, 1998

Watercolor

27 1/4 x 31 inches

Racine Art Museum, Joseph A. Marino Memorial Purchase Award from Watercolor Wisconsin ‘98

Photography: Jon Bolton

Influences on my work range from wash drawings of the 17th century illuminists who addressed the relationship between landscape and the expression of feeling, to an array of 20th century abstract artwork. Abstract color, shape and texture are an underpinning to all my realistic paintings, as are a sense of place and time, and related emotions.

Amy Arntson creates paintings inspired by her lifelong interest in, and familiarity with, the Great Lakes. Emerita Professor of Art at the University of Wisconsin-Whitewater, Arntson has traveled extensively and uses direct observation—sketches and photographs of places she visits—as the basis for her work. Frequently included in RAM’s Wustum Museum of Fine Art’s annual Watercolor Wisconsin exhibitions, Arntson is currently represented in RAM’s collection by two watercolor pieces.

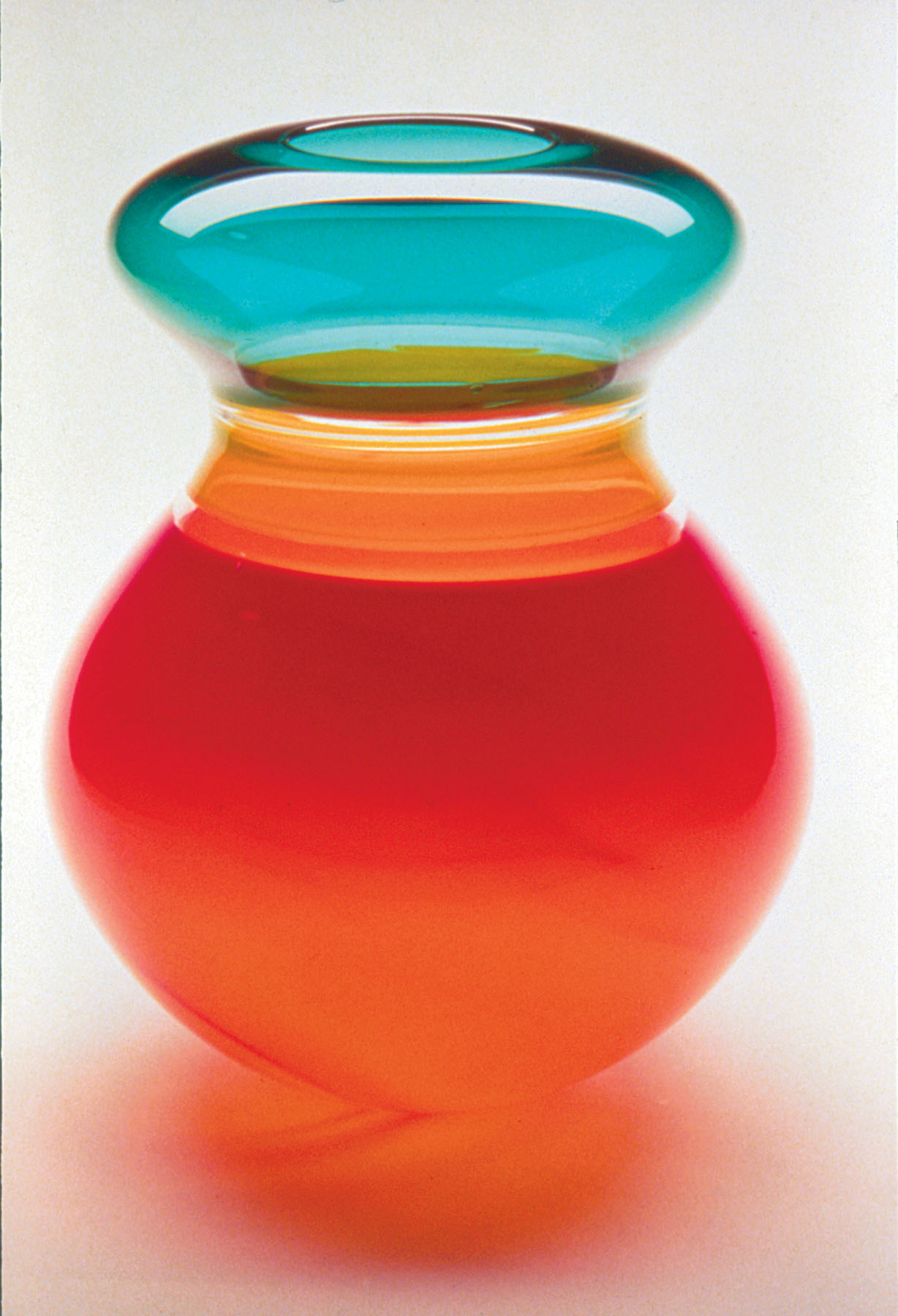

Sonja Blomdahl

Red/Yellow/Green Vessel, 1992

Glass

Racine Art Museum, Gift of Dale and Doug Anderson

Photographer: Jon Bolton

As an artist my focus has been with the vessel. In the vessel, I find the form to be of primary importance. It holds the space. In a sense, the vessel is a ‘history of my breath.’ It contains the volume within. If I have done things correctly, the profile of the piece is a continuous curve; the shape is full, and the opening confident. Color is often the ‘joy’ in making a piece. I want the colors to glow and react with each other. The clear band between the colors acts as an optic lens; it moves the color around and allows you to see into the piece. For me there is still much to explore. The relationship between form, color, proportion, and process still intrigues me.

Born in Waltham, MA, Sonja Blomdahl received a BFA from the Massachusetts College of Art where she studied with Dan Dailey, another artist in RAM’s collection. Prior to building her own studio in Seattle in the 1980s, Blomdahl discovered a way of working with glass that shaped her interest in the material. The incalmo technique—described as the joining together of two bubbles of glass—has become a hallmark for Blomdahl as she uses it to explore both color and form.

RAM is fortunate to have two vessels by Blomdahl in the collection. The artist was also featured on the November 19, 2021 episode of the Talking Out Your Glass podcast.

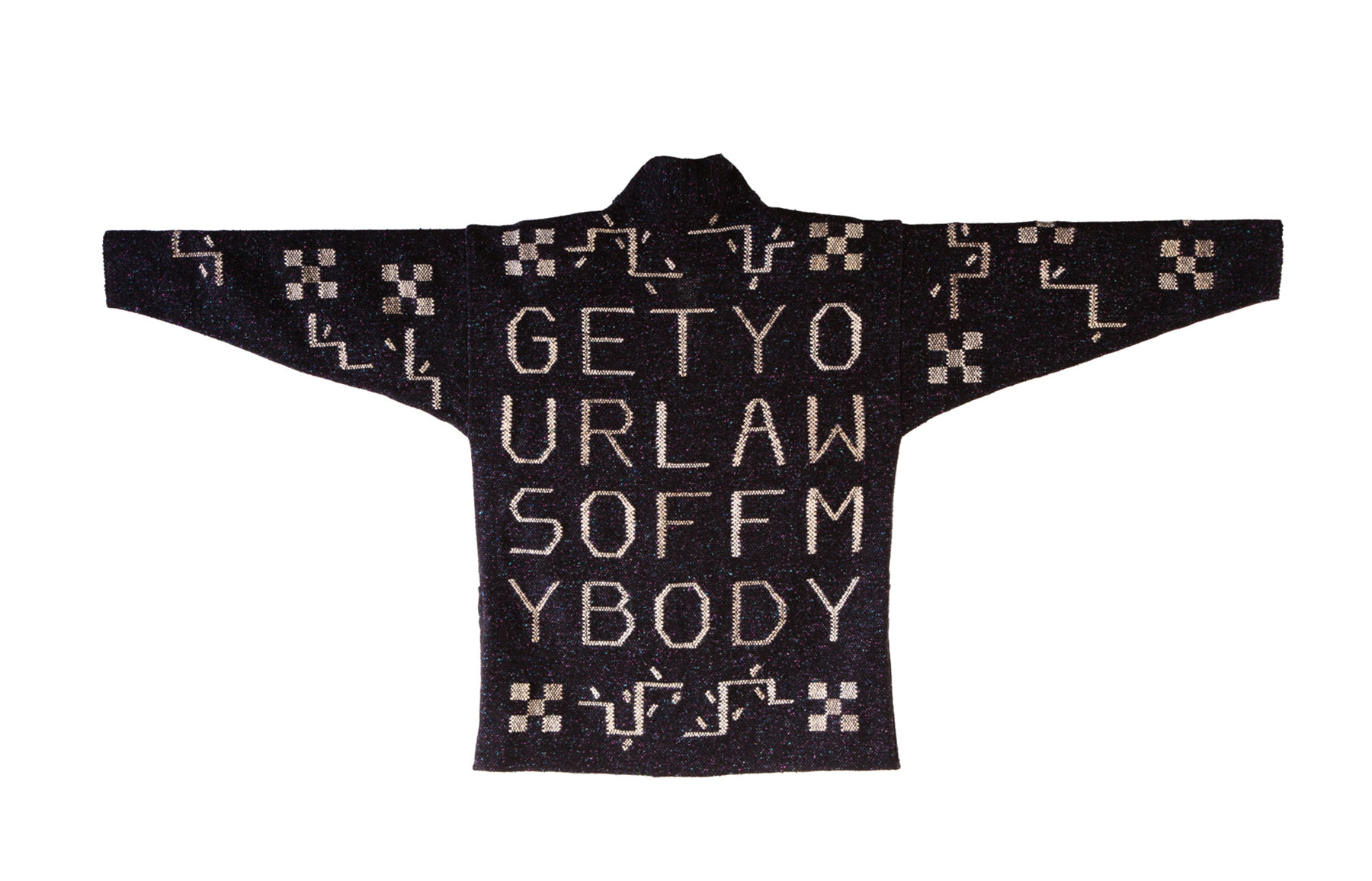

Barbara Brandel

Sampler (Coat), 1995

Dyed cotton, silk, and wool

35 x 64 inches

Racine Art Museum, Gift of Carol and Allen Naille

Photography: Jon Bolton

Making textiles and tapestry is slow work and is underappreciated in our culture. Working in that way opened my eyes and heart to the world’s history of the hand-made object. It only took several hundred years for many of those skills and art forms to disappear…I considered making art with handwoven cloth to be a noble fight.

While she currently spends more time with collage, assemblage, and painting, Barbara Brandel began her artistic career working with textiles. Brandel was most interested in wearable, pictorial work that built on her drawing and graphic interests. She was involved in the Art to Wear movement that blossomed in the United States in the 1980s and 1990s. Proponents of those ideas saw dress as a direct and creative connection between the body and the self as well as between the individual and the world at large. Paralleling the pursuits of artists working in other media, many of those associated with Art to Wear used fiber techniques that were traditionally identified as women’s work. Responding to the cultural climate, they regarded their use of these processes—combined with their personal vision—as subversive and a challenge to expectations.

Sampler, the jacket by Brandel in RAM’s collection, reflects her Art to Wear interests and echoes different twentieth-century cultural and social conversations involving women. The reference to samplers responds to the history of needlework and its associations with women—a sampler emphasized a needleworker’s skills—while the text corresponds to legal and political conversations, some of which were bubbling in the 1990s.

Emily Brock

The Café on 66, 1993

Glass, metal, wire, and paint

15 x 15 x 16 1/2 inches

Racine Art Museum, Gift of Benson and Francine Pillof

Photography: Jon Bolton

While she obtained a degree in clothing and textiles from Oregon State University, Emily Brock has been working primarily with glass as her artistic media for over 30 years. Employing a combination of various techniques including fusing, slumping, casting, and lampworking, Brock creates detailed dioramas—sometimes inhabited, sometimes not. The three works in RAM’s collection—a bakery/coffee shop, café, and the display room of an art collector—reflect the care and precision in Brock’s process, as well as a “fairy tale” quality that arises when these spaces are miniaturized and translated into glass.

Brock talks about how her work evolves:

My creative process is woven throughout every day. I am constantly gathering information, observing details, absorbing reflections on relationships, colors, and the printed word. It seems that without my intention all minutia is saved. At some point, sparked by a request or by chance, an idea or a fully formed image of a sculpture will present itself…It is important to sort the good ideas from the unattainable ones. After achieving some clarity of direction, the studio work time begins. It involves more decisions, ritual, mistakes, and repetitions of movement using equipment and tools. After an interminably long time of creating a tabletop landscape of chaos, a recognized moment of completion emerges.

Nancy Elkholm Burkert

At Rest on the Expressway, 1966

Watercolor on paper

14 1/8 x 18 3/8 inches

Racine Art Museum, WMAA Purchase Award from Watercolor Wisconsin 1967

Photography: Jon Bolton

Once a long-time resident of Wisconsin, Nancy Ekholm Burkert creates lush yet precise drawing in pen and ink or pencil as well as paintings in watercolor. Burkert is an award-winning book illustrator. Her first project was Roald Dahl’s James and The Giant Peach (1961) and her most celebrated was Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1972)—a New York Times Notable Book and a Caldecott Honor Book.

Employing a complicated technical process that spotlights her facility with light, shadow, and depth, Burkert has also been known to use her children as models. Notably, her stand-alone works such as At Rest on the Expressway, which is in RAM’s collection, often offer mysterious narratives that somehow match the tone of the fairy tales she illustrated. In 2013, this particular piece—a watercolor that was purchased from the Watercolor Wisconsin exhibition at Wustum in 1967—was voted 15th out of the top 100 works from RAM’s collection. It also had the notable distinction of being the only two-dimensional work to even place in the top 15.

Born in Colorado, Burkert moved to Wisconsin with her family when she was 12. She received both a bachelor’s and master’s degree from the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Burkert was married to fellow artist and Racine native Robert Burkert.

Patty Cokus

Cardiovascular Brooch: Flow, 2006

Glass, sterling silver, 2004 California shiraz, and extra virgin olive oil

5/8 x 1 7/8 inches diameter

Racine Art Museum, Gift of Friends in Honor of Karen Johnson Boyd’s 88th Birthday

Photography: Jon Bolton

Interested in “movement, connections, form, and thought,” Patty Cokus creates jewelry that sometimes incorporates unexpected materials. The three Cardiovascular Brooches that are part of RAM’s collection not only reflect her desire to explore movement, they also incorporate a variety of media and challenge expectations of wearability.

Each brooch incorporates thin glass rods filled with ephemeral substances, such as aspirin powder, salted butter, wine, and olive oil. The butter and wine look like blood—a fact that not only visually suggests a relationship to the heart but also connects back to substances that are associated with the health—good or bad—of the human body. Shifting parts on the brooches react in various ways as the wearer moves. This fluctuation, reliant on the connection between the piece and the wearer, gives the work a sense of play and dynamism.

Currently living in the Pacific Northwest, Cokus received a BFA from the Massachusetts College of Art. She exhibits her work nationally and internationally.

Kéké Cribbs

Grainne Uaile, 1991

Glass and painted wood

22 1/4 x 41 3/8 inches

Racine Art Museum, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

Photography: Jon Bolton

Inspired by the history and architecture of ancient dwellings and towns she encountered while living in Ireland and Corsica, Kéké Cribbs draws on the narrative potential of dreams, the past, and mythology to create work that often combines glass and other media. Cribbs builds imagery through etching surfaces as well as sculpting and painting wood. In some pieces, she employs a specialized technique that allows her to develop layers of color by firing vitreous enamel on the reverse side of glass. Reflecting on the source of content in her work, Cribbs describes her process:

I think it could be fair to say that my everyday life, my art and my dream time, are all of one…The world for me is best deciphered and analyzed through symbols which reveal compassion for the observed…I use this imagery to share my translations of the world as I perceive it to be.

RAM has four works by Cribbs in the collection.

Karen Dahl

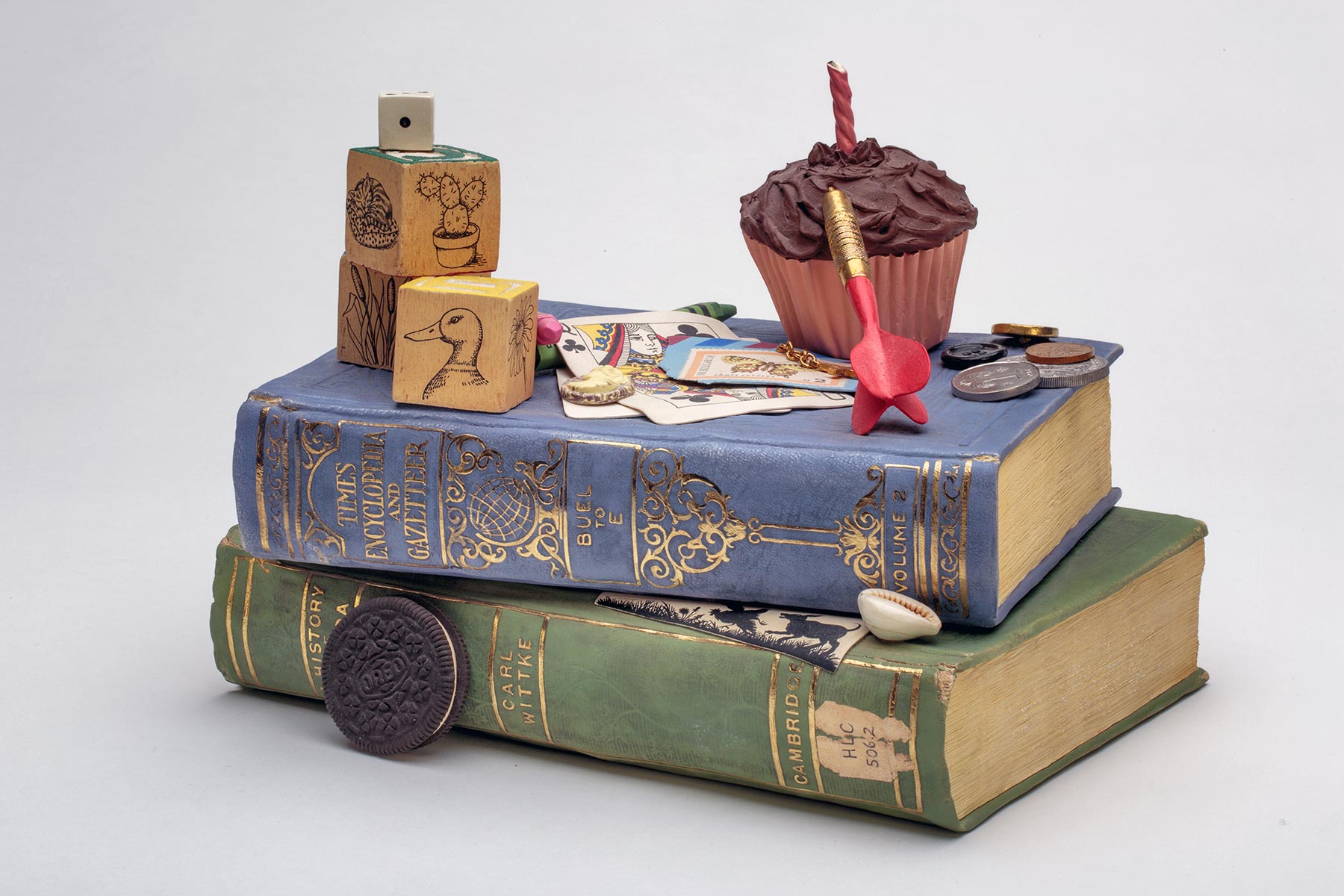

Buel to E, 1988

Glazed white earthenware with lustres and paint

6 1/8 x 8 5/8 x 5 7/8 inches

Racine Art Museum, Gift of Dale and Doug Anderson

Photography: Jon Bolton

As a child leafing through art books, and later visiting art galleries during my travels, I have always gravitated towards early European still-life depictions—the more realistic, the better. Not surprisingly, the objects surrounding me in everyday life, both natural and man-made, have always inspired me. I am a compulsive collector and I adore the bizarre and unusual. I use faithfully reproduced, familiar objects as visual tools to seduce viewers into my work…The narrative is in the individual objects, whereas the combined allusion is broad and amorphous and may vary according to the experiences of the viewer. My work is trompe l’oeil with layers of mystery, reflection, humour [sic] and occasional menace.

Canadian artist Karen Dahl has become well-known for her ceramic sculptures that confound viewers. Dahl’s works incorporating “trompe l’oeil,” French for “deceive the eye,” appear to be assorted objects arranged into groupings—sometimes fantastical, always intriguing. In reality, they are life-size interpretations of commonplace objects crafted with hand-built and press-molded clay, which is hand-painted and airbrushed with glazes.

Mabel Dwight

Buried Treasure, 1939

Lithograph, uneditioned

13 x 10 inches

Racine Art Museum, Works Projects Administration, New York Federal Art Project

Photography: Jon Bolton

This print, Buried Treasure by Mabel Dwight, highlights the hard times that many experienced in the US between the Great Depression of the 1930s and World War II. Artists like Mabel Dwight—who is identified as one of the premier printmakers in the country during the first half of the twentieth century—wanted to highlight the reality of daily circumstances. Her realistic style, which often reflected her humor as well as her compassion, was described as having a “gentle tone.” Dwight was able to take a light-hearted approach despite a life marked with hardships and her shift towards more radical political views.

(Left)

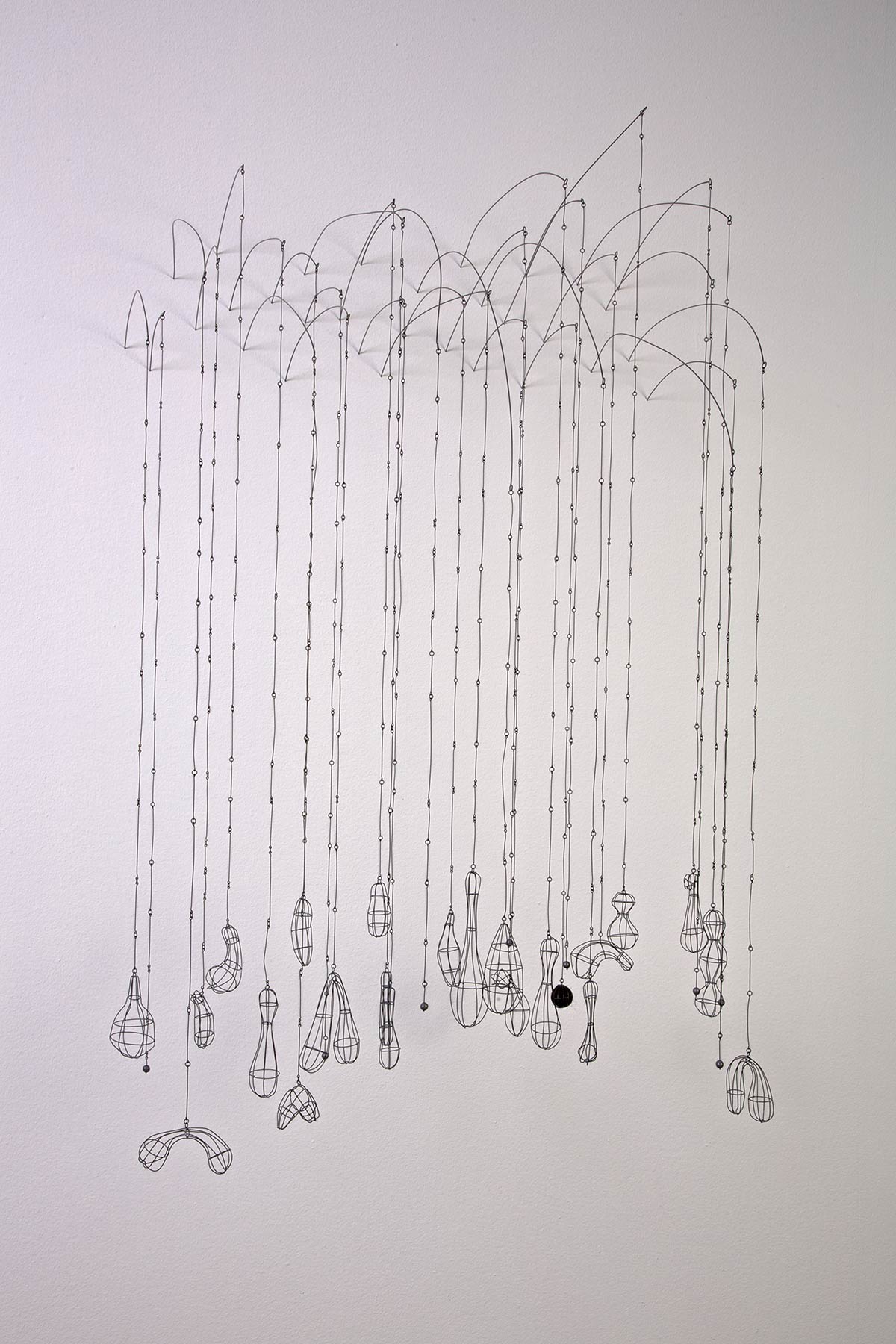

Carol Eckert

Staff of the Fire Shaman, 2000

Dyed cotton, wire, painted wood, metal, and glass seed beads

70 1/2 x 6 3/4 inches diameter

Racine Art Museum, Gift of the Artist

(Right)

Carol Eckert

Staff of the Prophets, 2000

Dyed cotton, wire, painted wood, metal, and glass seed beads

73 x 10 1/2 x 4 inches

Racine Art Museum, Gift of Karen Johnson Boyd

Photography: Jon Bolton

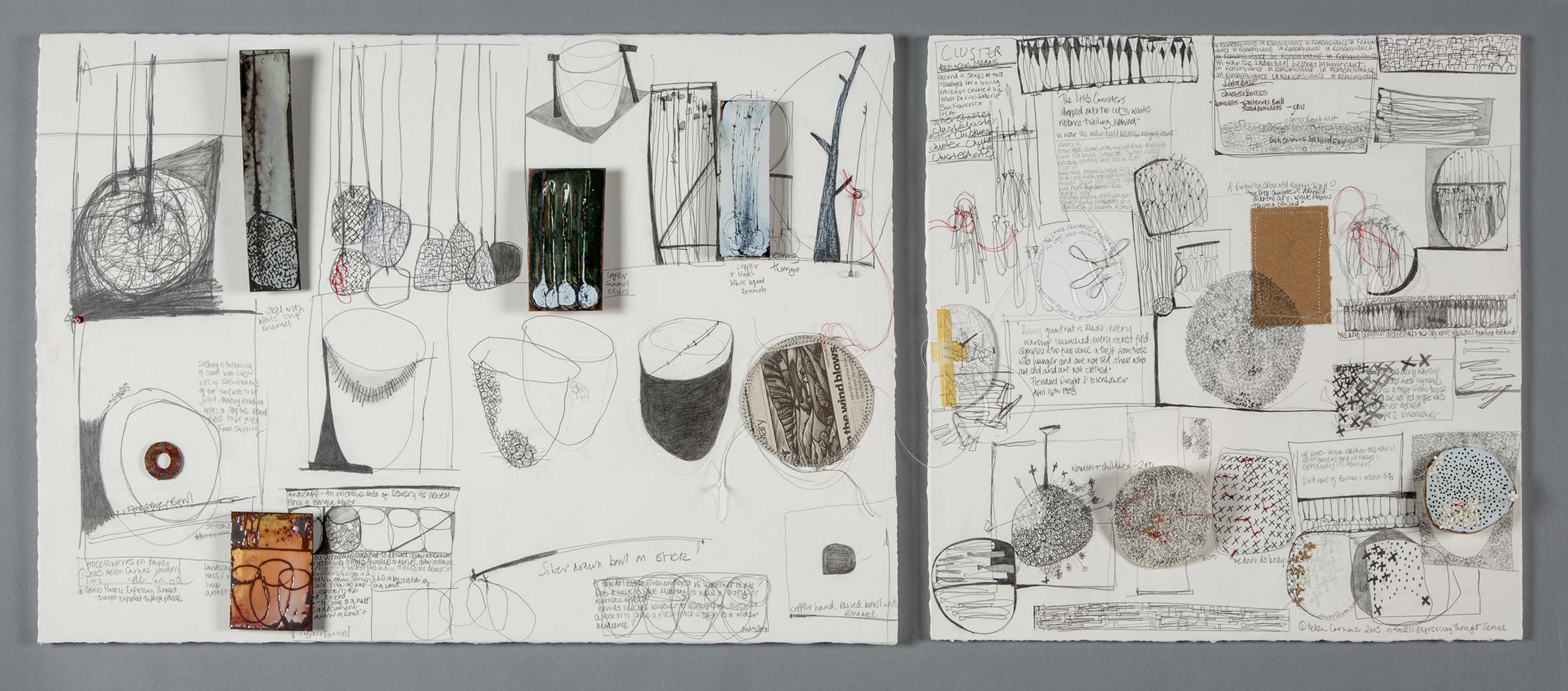

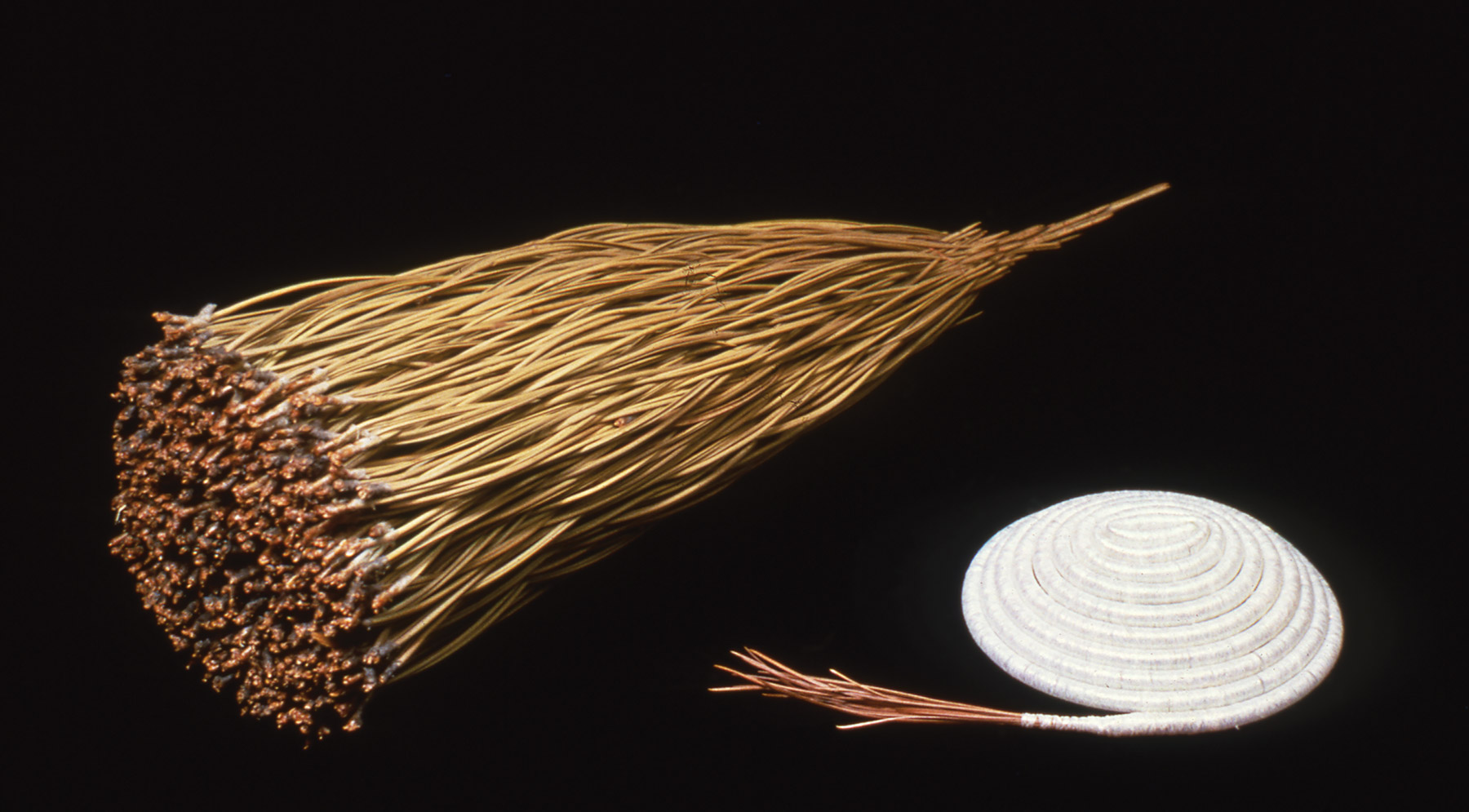

Inspired by myths, legends and other tales, Carol Eckert creates compelling sculptural narratives using an ancient basketry technique known as coiling. Eckert’s visual stories are populated with a menagerie of animals both real and mythical, such as snakes, birds, crocodiles, and basilisks. The creatures themselves—as well as the objects, vessels, and wall reliefs that they adorn—are constructed of a thin copper wire wrapped (or “coiled”) with cotton embroidery floss. With over 20 works in the collection, RAM is the biggest known repository of Eckert’s work. The objects and images in RAM’s collection span the years 1988 through 2009, and represent both small-scale and larger pieces, as well as color sketches.

A quote from Eckert’s interview for the Archives of American Art illuminates how, as a young mother, she found a way to incorporate her creativity into her daily life:

At one point, when I was working with clay, I had kids at home. And I lived a really interrupted life. And with clay, if you have to leave it at the wrong time, it’s just – it gets ruined…And with the coiling, I could pick it up and put it down. And often, my days were interrupted. In those days, if I could grab 30 minutes here and two hours there, I could still make progress in a day, and it was so much less frustrating.

And the coiling was also very portable. So I spent plenty of time sitting in cars while kids were at lessons, making pieces; I can get work done on airplanes. So it fit into my life; it’s also my kind of coiling. It doesn’t need water; it’s not messy, so it fit very nicely into the studio space I had and into the whole fabric of my life.

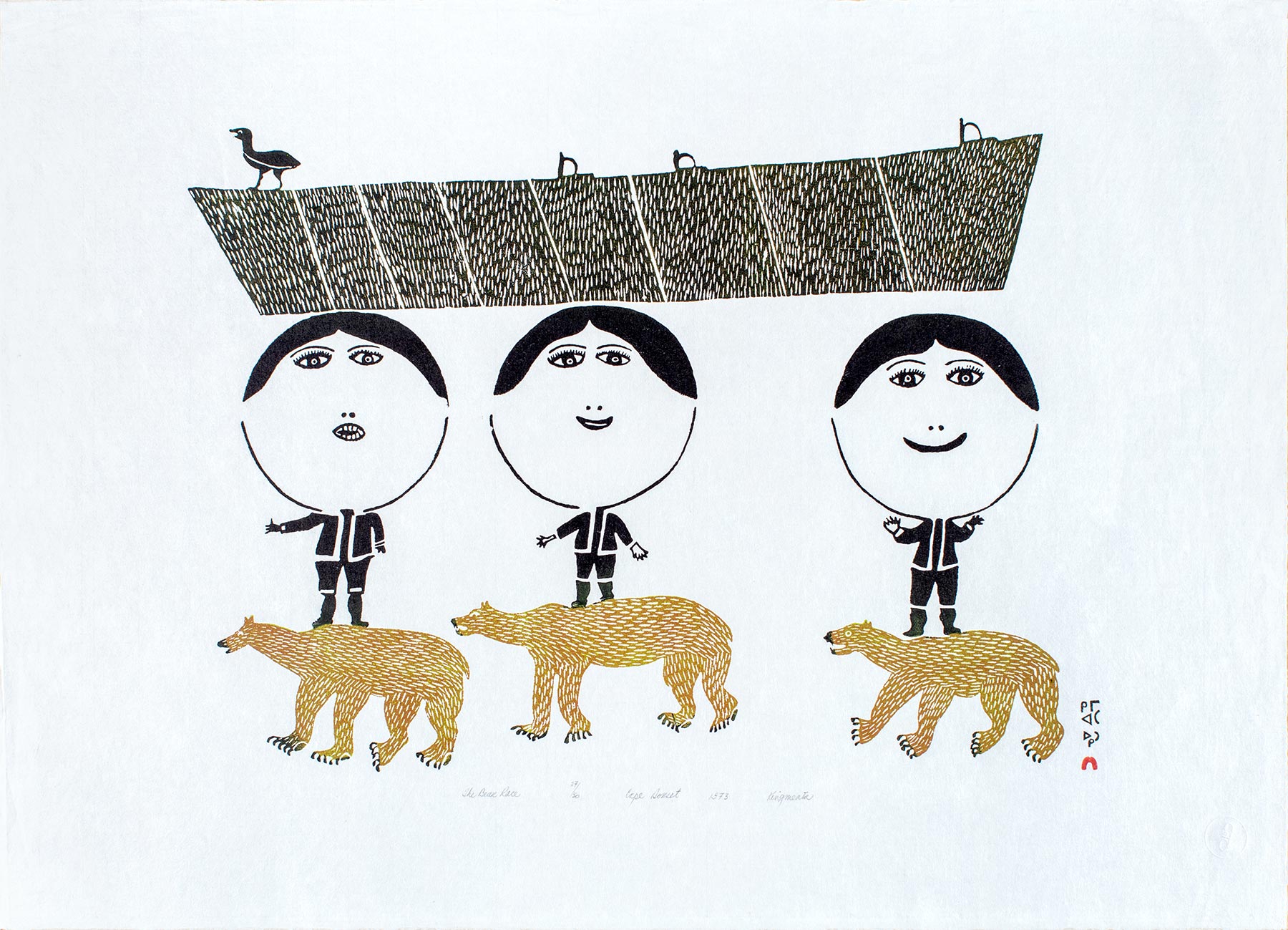

Kingmeata Etidlooie

The Bear Race, 1973

Stonecut, edition 27/50

34 x 24 inches

Racine Art Museum, Gift of Karen Johnson Boyd

Photography: Jon Bolton

Printmaking was introduced to Kinngait (formerly known as Cape Dorset) in Arctic Canada in the 1950s. With purchases being made from cooperatives or artists directly, printmaking as a creative practice has also become a primary economic stream for multiple generations of Inuit artists. Home to America’s largest contemporary craft collection, RAM also has an extensive collection of works on paper that currently includes eight prints from Kinngait artists.

Kingmeata Etidlooie (1915–1989) began to carve and draw after the death of her first husband and became involved in a cooperative known for its printmaking studio with her second husband. Favoring animals and birds as subject matter, she became well-known for her willingness to experiment with materials—incorporating watercolors and acrylics with drawing.

Arline Fisch

Woven Square Brooch, 1986

Sterling silver and anodized titanium

4 1/8 x 4 1/8 x 1/8 inches

Racine Art Museum, Gift of Karen Johnson Boyd

Photography: Jon Bolton

Concerned with creating unique works that enhance the wearer’s persona, Arline Fisch has created elaborate, yet wearable jewelry for decades. Best known for her introduction of weaving techniques into the field of contemporary jewelry, Fisch knits, weaves, crochets, braids, and plaits precious metals, creating supple textures and reflective planes. Describing the metal wire that she uses as her primary medium as “soft and warm,” Fisch most often considers the body as the destination for her pieces, emphasizing their wearability—comfort, flexibility, and movement—as much as their formal aspects—ornament, form, and color.

Born in Brooklyn in 1931, Fisch has a BS in art education from Skidmore College, Saratoga Springs, New York, and an MA from the University of Illinois. In 1956, she went to Denmark where she studied silversmithing at the School of Arts and Crafts in Copenhagen. From 1961 to 2000, Fisch taught at San Diego State University. Among her many professional accomplishments, she won the American Craft Council Gold Metal in 2001, is a three time Fulbright scholarship winner, and spent three years as the president of the Society of North American Goldsmiths (SNAG), of which she is a founding member.

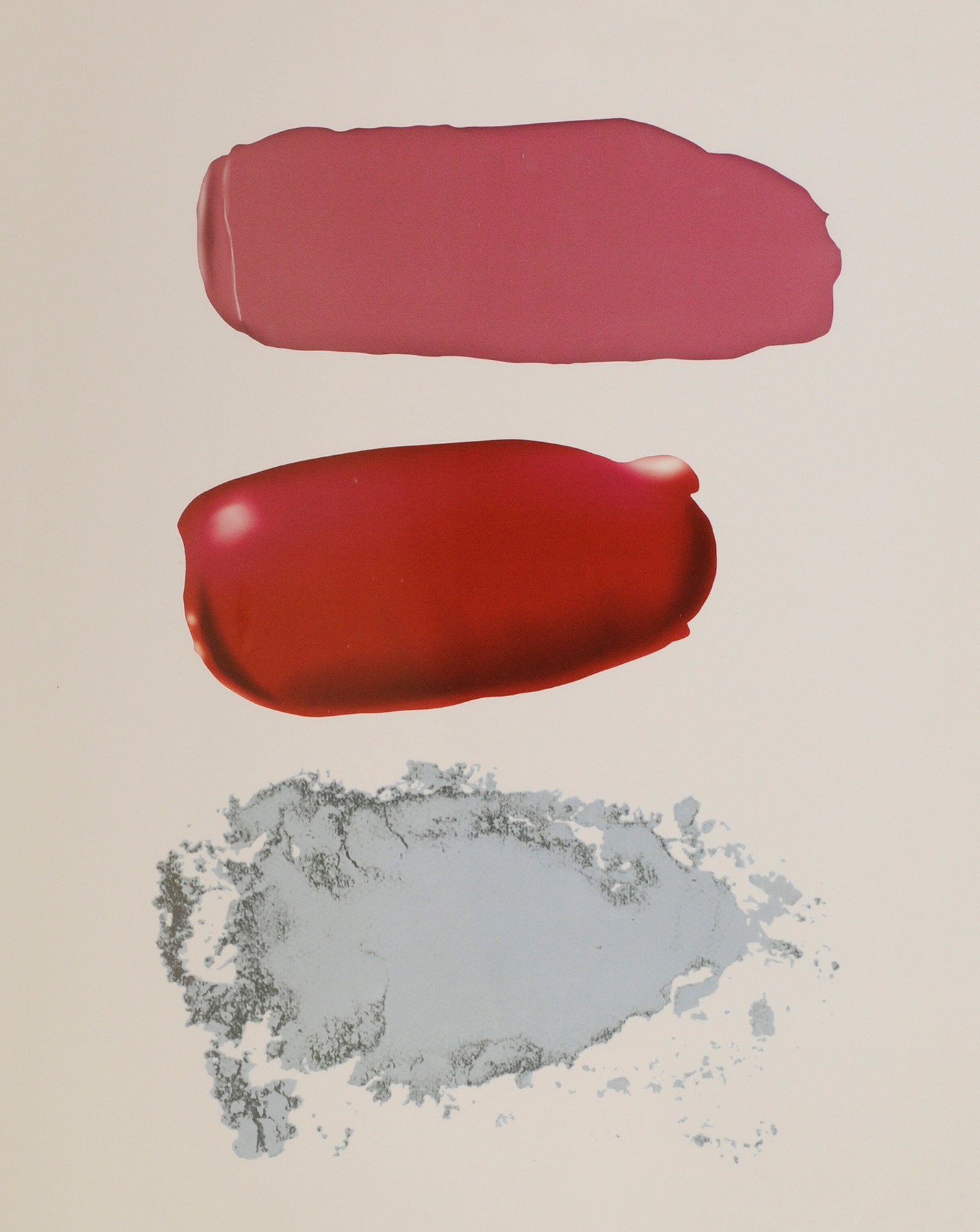

Sylvie Fleury

Happy Clinique from the Sequences Series, 1996–98

Serigraph and offset lithograph, edition of 60

16 1/4 x 11 inches

Racine Art Museum, Gift of Marshfield Clinic and Kohler Foundation, Inc.

Photography: Kohler Foundation, Inc.

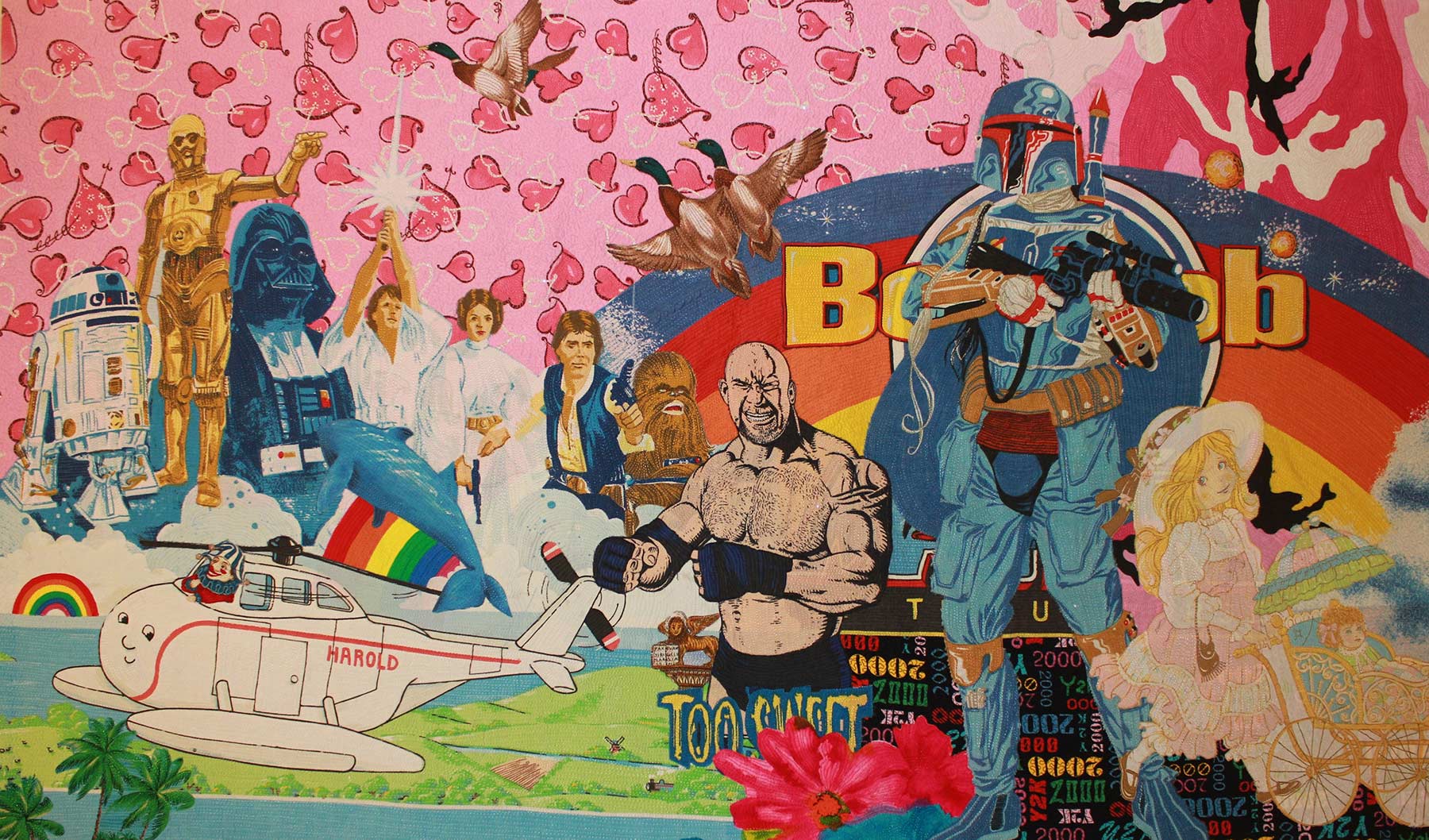

For over three decades, influential Swiss artist Sylvie Fleury has been investigating cultural desire, luxury, consumption, and excess. Both resonating with and diverging from Linda Dolack, whose bead-covered candy boxes were profiled recently, Fleury takes aim at the manipulation of marketing which—in the context of her work—is usually concerned with gender and sentiment. She combines various inspirations, such as fashion, shopping, status symbols, magazine covers, slogans, and even Formula One Racing, to create sculpture, installations, neon signs, and prints.

Fleury’s Happy Clinique prints from the Sequence Series are recent additions to RAM’s works on paper collection. Described simply, each print seems abstract—compositions comprised of three different colored stripes with uneven edges. The title provides some context—Clinique is a well-known makeup brand. Arguably, many people interested in makeup might see immediately that these are color palettes showing suggested combinations of lipstick, eye shadow, and other beauty products. The fact that some people, due to gender or lack of interest, would not have a frame of reference for understanding the inspiration, and that those who recognize what is depicted would associate it with high end luxury makeup, is part of the artist’s point.

Laritza Garcia

Cerulean Spin Brooch, ca. 2010

Powder-coated steel and silver

4 3/8 x 2 1/2 x 1 inches

Racine Art Museum, Gift of Robert W. Ebendorf and Aleta Braun

Photography: Jon Bolton

My personal development and professional training have led me to believe that playful attitudes help people cope, problem solve, and can offer emotional lightness. My jewelry pieces present familiar childhood imagery in efforts to drive forth the restorative nature of imaginative behavior. Gestural objects in vibrant colors materialize as graphic triggers that reconnect people with regenerative powers of playfulness. My approach encompasses a dual investigation of gestural drawing and traditional metalworking practices such as hand piercing metal. I use inks and calligraphy brushes to make linear illustrations that are the base from which ideas are developed into refined pieces of adornment. The intent of this body of work is to infuse wardrobes and activate walls with whimsical pieces that bring levity to the forefront.

Originally from the border area of Reynosa, Mexico, and McAllen, Texas, Laritza Garcia values her involvement in youth outreach—as well as painting and illustration—as an influence on her jewelry design. She received a BFA from Texas State University and an MFA from East Carolina University. In addition to being a studio jeweler and participating in juried craft shows, she has been a visiting artist at locations across the country and teaches in the School of Art and Design at Texas State University.

Terri Gelenian-Wood

Salad Servers, 2005

Sterling silver and Corian®

11 1/4 x 2 5/16 x 1 1/4 inches

Racine Art Museum, Gift of Paul Wood

Photography: Jon Bolton

All of these works are tabletop objects with a function of their own. Whether they are tools for eating and serving, or learning tools for contemplating the dynamics of relationships, they all express involvement among the viewer, the object, and the maker. They all can be picked up with a dominant hand or both hands and observed. Engineered into my loyalty to traditional silversmithing techniques is my attraction to industrial materials and processes. This is evident in the use of countertop laminates and solid surfacing materials (e.g. Corian®) …My fascination with silver, used in conjunction with alternative materials, began for reasons of adding color and often results in a bit of irony.

Racine native Terri Gelenian-Wood (1955–2006) is among a group of artists in RAM’s collection from whom the museum has an archive of several objects representing their work. Best known for tableware that combines high polish sterling silver with intensely colored plastics—such as Corian® or Formica®—Gelenian-Wood received a BFA from the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee and an MFA from the Tyler School of Art, Temple University, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Dorothy Hafner

Confetti Tea Set, 1981

Glazed porcelain

Various dimensions

Racine Art Museum, Gift of Karen Johnson Boyd

Photography: Jon Bolton

Trained as a painter and sculptor, Dorothy Hafner has made her name working with clay and glass. With the establishment of the production firm, Art and Dining in 1979—and for about 15 years after—Hafner designed porcelain tableware for organizations such as Tiffany & Co. as well as Rosenthal, a renowned porcelain manufacturer in Germany. Since 1997, she has worked exclusively with glass.

As evidenced by the image of pieces from the Confetti Tea Set, Hafner expresses her love of “color plays, evocative lines and idiosyncratic abstractions” regardless of the artistic materials she chooses. Hafner has created one-of-a-kind hand built works as well as small edition production pieces. RAM’s collection includes components from two of her iconic tableware lines.

Nancy Hild

Anger from the Allegory of the Seven Sins Series, 1996

Acrylic on panel

20 x 17 inches

Racine Art Museum, Gift of Linda R. James and Mary F. McAuley

Photography: Jon Bolton

Certain objects become for me recurrent obsessions over a period of time—such as animal forms…I enjoy the paradox of the ordinary as exotic, the incongruity of plastic flamingos on Midwestern lawns, the inherent sensuality of a Holstein cow taken out of context…

I find the challenge of presenting the fantastic as believable, fact as fiction, central to and inseparable from the somewhat perverse sense of humor essential to my work.

Born in the 1940s, Nancy Hild spent most of her artistic career in Chicago where she had over 70 exhibitions during her lifetime. Her work has been shown internationally in countries such as the United Kingdom, South America, Africa, China, and Mexico. Hild’s paintings, representational yet often narratively ambiguous, showcase theoretical connections between women’s equality and animal rights.

Hild completed a painting series titled Allegory of the Seven Sins in 1996. The allegories are each articulated through metaphorical and poetic images that combine a truncated body with delicately posed hands framing an animal. Hild’s biographer, Linda R. James, commented that the artist considered this series to be “one of her finest.”

Jan Huling

Jackie’s Nut, 2012

Seed beads and found objects

10 1/2 x 11 x 5 1/4 inches

Racine Art Museum, Gift of David and Jacqueline Charak

Photography: Jon Bolton

My goal and technique has been the transformation of mundane sculptural forms into spectacular, meaningful, hypnotic works of art. Each piece is a meditation of color and form, pattern and texture that is allowed to grow organically without plans or sketches. With each new row of beads, I more clearly see the personality of the piece emerging and it tells me what color needs to follow, what line needs to intersect. I listen.

Jan Huling, a self-described “beadist,” was once a product designer. Now Huling uses an air pen to coat found objects with glass seed beads, and sometimes with buttons, coins, and tokens. Her additions add layers of meaning to mundane objects, ultimately suggesting something fantastical or mythical.

Cherry Barr Jerry

The Collector, 1957

Graphite on paper

12 x 13 inches

Racine Art Museum, Gift of Dorothy Haas in Memory of Arthur P. Haas

Photography: Jon Bolton

I did things that pleased me and if it didn’t please me, it was destroyed two or three years later.

Cherry Barr Jerry (1909–1993) was born in Colorado. After studying at the National School of Fine and Applied Arts in Washington, DC, she went to Michigan and worked at the Index of American Design, part of the Federal Art Project during the Great Depression of the 1930s. While in Michigan, Cherry met and married Sylvester Jerry, who would become the first Director of the Charles A. Wustum Museum of Fine Arts. She and her husband lived in a portion of the Wustum house with their three children in the 1940s and 1950s. While Sylvester was the official Director of Wustum, it is clear that Cherry Jerry was a pivotal figure on the site.

For 28 years, Cherry Jerry taught adult and children’s art classes in watercolor, drawing, enameling, lapidary, bookbinding, papermaking, and creative stitching techniques at Wustum. She also taught for the University of Wisconsin Extension System and University of Wisconsin-Parkside. Her work was shown in exhibitions across the US, including at the Art Institute of Chicago and Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

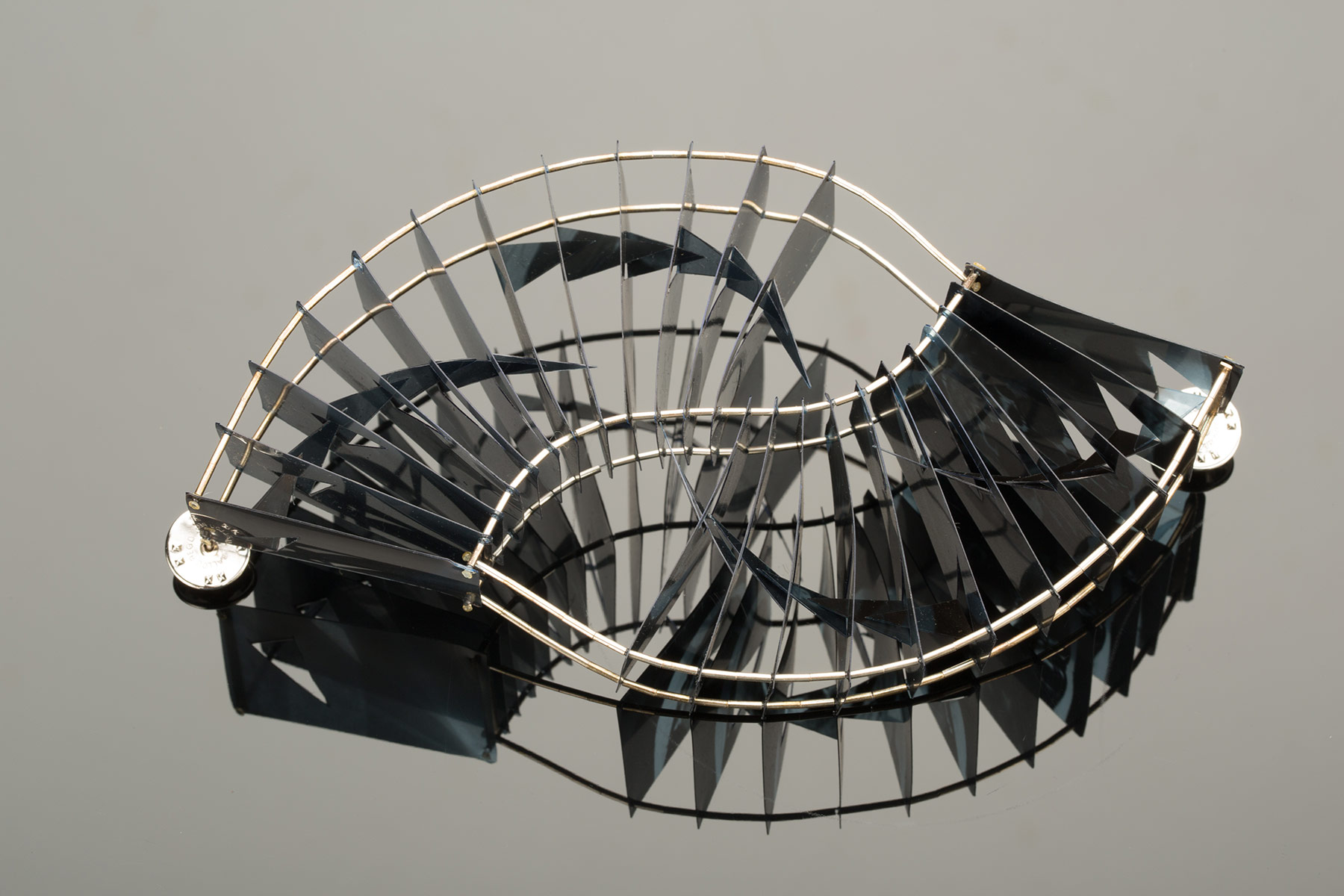

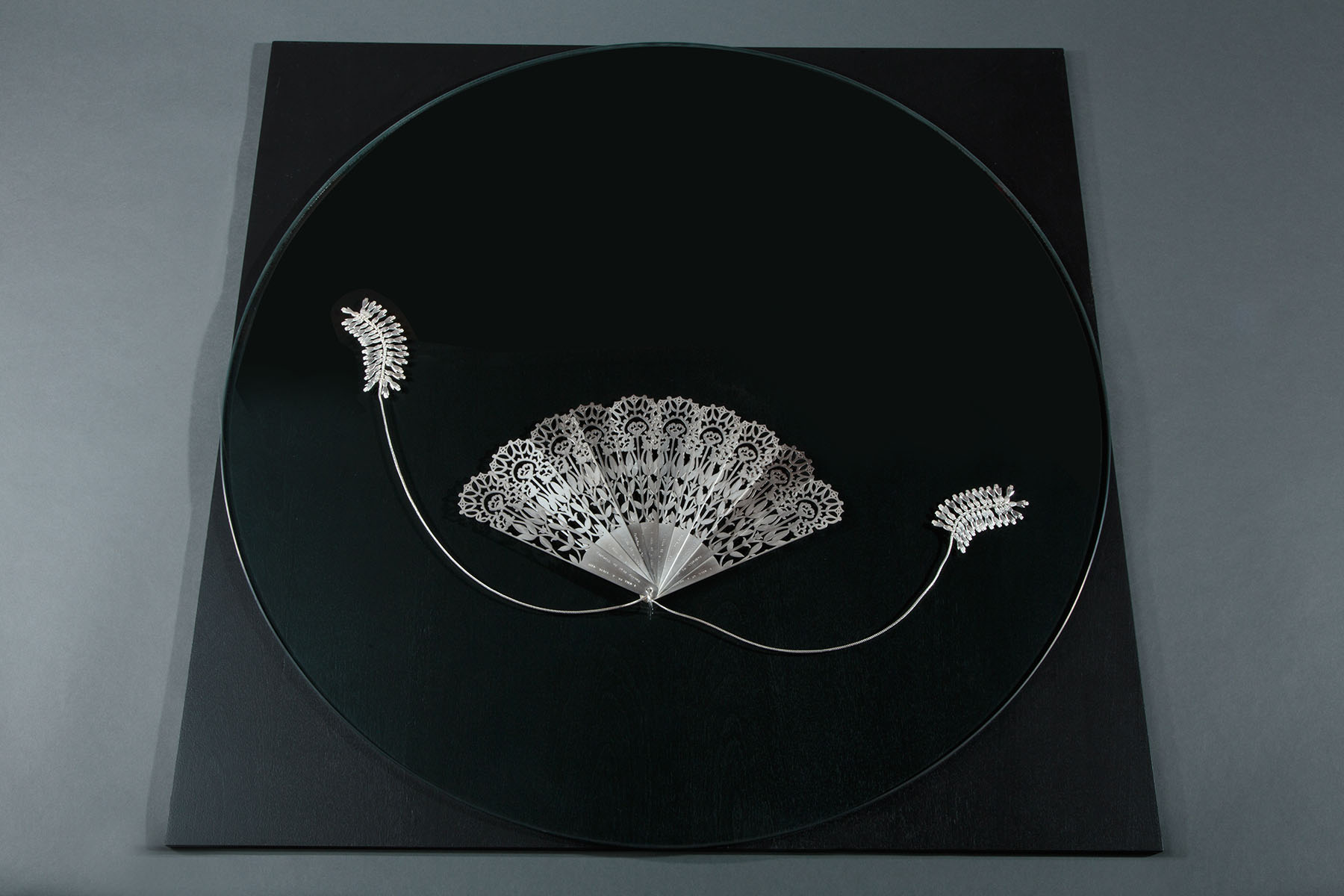

Hai-Chi Jihn

Mother, a Beautiful Young Lady, 2000

Sterling silver, glass, and wood

Racine Art Museum, Gift of Dale and Doug Anderson

Photography: Jon Bolton

Utilizing exacting metalsmithing processes, Wisconsin-based artist Hai-Chi Jihn creates sculpture that addresses her Chinese heritage, issues of femininity, and women’s perceived social roles. Born in Taiwan, Jihn earned a BA in textile and clothing design from Fu Jen University in Taiwan and an MFA in metalsmithing from UW-Milwaukee.

Mother, A Beautiful Young Lady, a fan sculpted by Jihn from silver and inscribed with text is featured in RAM’s collection. With elements constructed to look like lace, this piece is connected to other works she has created that use the idea of dowry—gifts given to a prospective bride’s family—to investigate the complex circumstances associated with marriage beyond love or companionship. The text, which Jihn describes as a “bride’s promise to her parents before she sets off to the wedding,” repeats on blades of the fan. It reads:

Farewell my dear father,

I will be a loyal wife;

Farewell my beloved mother,

I will be a diligent wife.

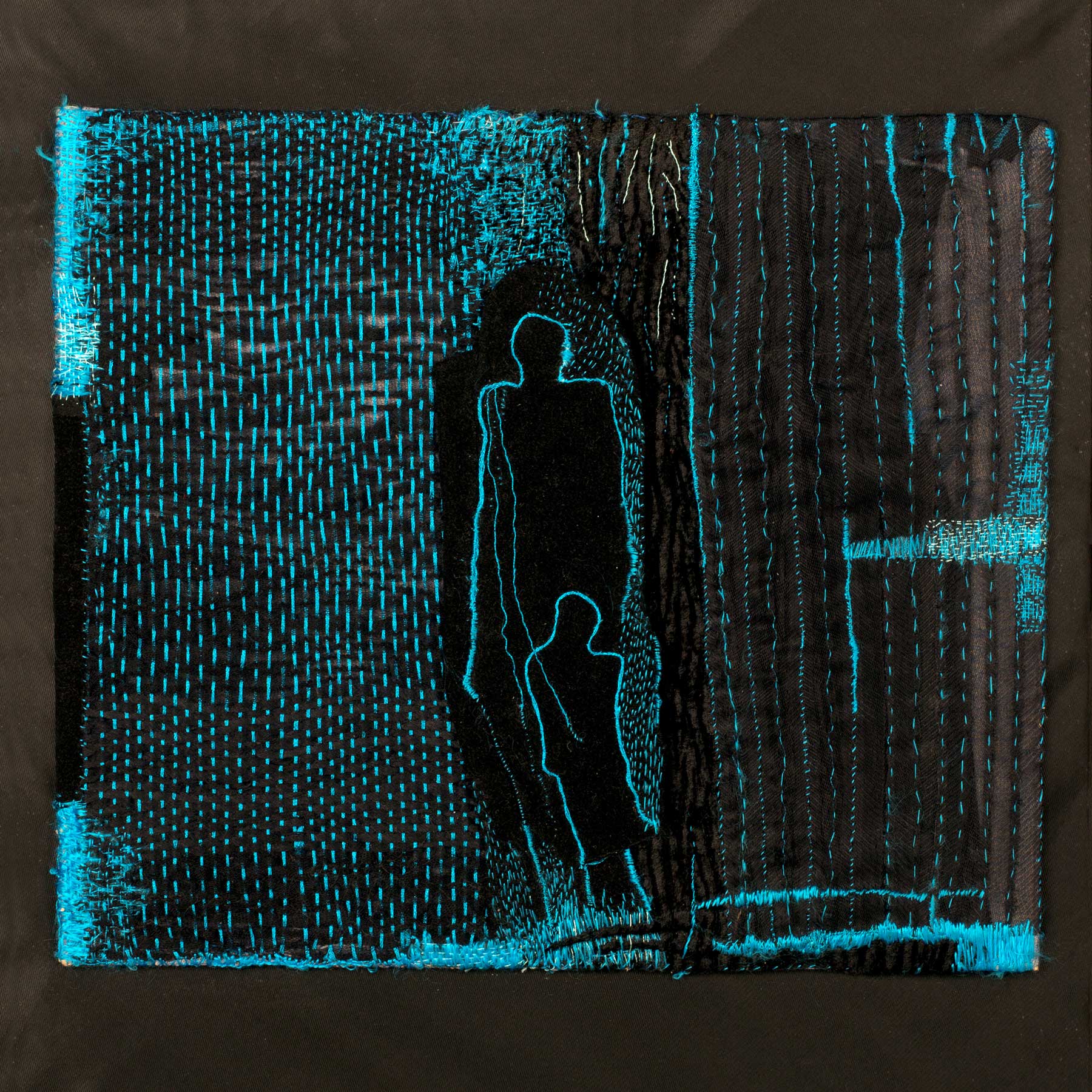

Rosita Johanson

Tales My Father Told Me, 1994

Dyed cotton fabric, dyed cotton thread, metallic thread, and wood

Racine Art Museum, Gift of Mobilia Gallery, Cambridge, MA

Photography: Jon Bolton

From a family of people skilled at working with their hands, Rosita Johanson (1937–2007) was long drawn to thread and fabric, as well as expressing herself visually. As a child she began making her own clothes and often drew and sketched. While she became a dressmaker by trade, Johanson was largely self-taught as an artist. Drawing on childhood memories, her imagination, and some topical political and social issues, she pieced together compositions using appliqué, machine embroidery, and hand-stitching. Her designs, which often began as sketches, culminated in layers of thread and fabric.

Johanson’s pieces play with the historical links between stitched work and the labors of women. Unlike other contemporaries who used handwork techniques to question the perceptions of gender and so-called women’s work, Johanson seemed to embrace the materials and techniques because they allowed her to tell the stories she wanted to tell. Having said that, her work helped to challenge the boundaries of fiber art in the late twentieth century.

RAM is the only public institution to have over 20 works by this significant artist.

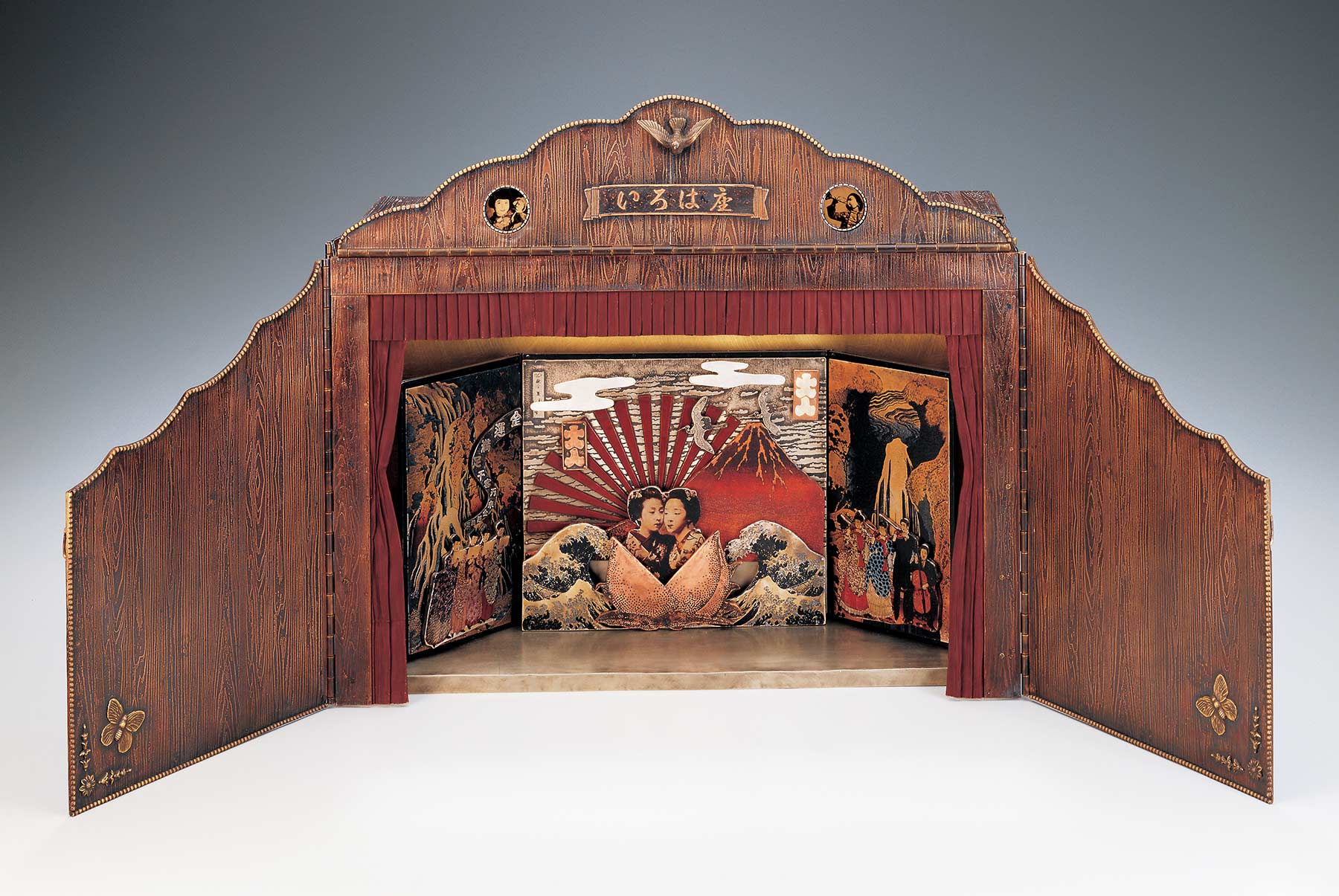

Mariko Kusumoto

Byobu, 2004–06

Copper, nickel, silver, brass, sterling silver, magnets, and artist-rendered decals

15 x 30 x 9 1/2 inches

Racine Art Museum, Gift of Karen Johnson Boyd

Photography: Johansen Krause

Growing up in a 400-year-old temple, I was always surrounded by ancient things like tansu (Japanese chests of drawers), faded paint on wood, Buddhas and their ornaments, etc. I was especially fascinated by the tansu. When I opened the drawers, I could never anticipate what would appear from the darkness. I had mixed feelings of excitement and fear whenever I opened it. It was a great wonder box to me.

Artist Mariko Kusumoto creates magical worlds that both delight and mystify. Using a variety of metalsmithing techniques, Kusumoto crafts elaborate miniature stage sets with multiple doors, moving parts, compartments, and drawers as well as the characters and props to inhabit them. Her love of theater and performance is underscored by the potential interactive elements of each piece—they can be presented as closed boxes and containers, or opened and manipulated so that their stories unfold. The narrative potential is even more complex as many elements are created in the form of brooches, necklaces, and bracelets that can be worn and thus seen in a wholly different light. These metal sculptural boxes, which also incorporate found objects, reflect Kusumoto’s Japanese identity and influences from her childhood. For several years, Kusumoto has also been making fiber work, especially adornment such as neckpieces that look like bubbles and organically-inspired brooches. She has stated that she likes the contrast between the types of materials she favors, where fiber is almost the “opposite” of metal.

Ke-Sook Lee

Apron # 4: Seed Pods, 2004

Rice paper, embroidery thread, tarlatan, doilies, and earth pigment

65 7/8 x 55 1/2 inches

Racine Art Museum, Gift of Barbara and Steven Gross

Photography: Jon Bolton

Born in South Korea, Ke-Sook Lee—who is now based in California—moved to the US in 1984. Lee earned a BFA from Seoul National University in Seoul, Korea in 1963 and another BFA from the Kansas City Art Institute, Kansas City, Missouri, in 1982. Her work is exhibited and collected internationally.

Wanting to focus on womanhood, Lee moved away from painting and began to work with fibers. Over time, she expanded the scale and scope of her pieces, moving towards large work and installations. Lee focuses on domestic themes and aspects of the natural world, often as metaphors and parallels to life experiences. Her work purposefully draws on generations of familial, female-oriented history.

As noted in a statement about her work:

The women of her grandmother’s generation who were not taught to write instead expressed themselves through hand-embroidery. As she makes her marks, she focuses on the experience of sewing, stating, “I am interested in relinquishing conscious control of my hand, letting the thread and needle respond to my memory and experience of my womanhood.”

Silvia Levenson

Panchina Di Vetro (Bench of Glass), 2002

Glass, metal, and AstroTurf

20 x 47 3/16 x 10 1/8 inches

Racine Art Museum, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

Photography: Jon Bolton

I was born in Buenos Aires in 1957. I was part of a generation that fought to change a society that we perceived as terribly unfair. In 1976, when the Army seized power, I was nineteen…What happened between 1976 and 1983, changed my life, and influenced my work as an artist. A key part of my job consists of revealing, or making visible, what is normally hidden or cannot be seen, and I use glass to represent this metaphor. We have always used glass to preserve food and drinks, I use glass to preserve the memory of people and objects for the future generations.

Silvia Levenson left Argentina in her early twenties amidst political unrest and family tragedy. While her work can sometimes consider the domestic, daily life, childhood, social expectations, and fashion, it is rooted in her personal experiences and the universality of the human condition. Fascinated with the beauty of glass as a material, Levenson is compelled to push past its aesthetic, engaging its potential to convey the content she explores in her work.

RAM currently has three works by Levenson in the collection.

Lindsay Locatelli

Cactus at Dusk, 2018

Polymer, cactus skeleton, 18k-gold leaf, wood, and paint

13 x 13 1/2 x 2 inches

Racine Art Museum, Gift of the Artist

Photography: Locatelli Studios

I’m drawn to creating contemporary art jewelry highlighting nature’s bold spirit and character…Wearing the work activates a tactile experience and animates these ideas as an adornment. My jewelry largely becomes mobile bodies of wearable art; meant to be both worn and observed.

Born into a creative family that includes a clothing designer, a painter, a potter, and a musician, Lindsay Locatelli (Wazo Designs) embraces material exploration. She currently uses polymer—as well as wood, gold leaf, and other materials—to create adornment that is often based on her experiences with the vibrant landscape, flora, and fauna of the American Southwest. Intent on hand-fabricating—and drawing on a background in both graphic and furniture design—Locatelli not only creates art jewelry that straddles the line of wearability, she also often considers the place of adornment off the body. Locatelli’s work in RAM’s collection is a large neckpiece that can be displayed with a wall-mounted support in a contrasting texture and color. This is a true sneak peek as this piece has not even been out on display at RAM yet.

Locatelli is one of the younger artists in RAM’s collection, the winner of a 2017 Minnesota Artist Initiative grant and a repeat at American Craft Council shows, she is pushing the possibilities of both polymer and contemporary art jewelry.

Carlotta Miller

Saturday Morning Market, 2015

Watercolor

34 x 24 inches

Racine Art Museum, Joan M. Spinks Memorial Purchase Award from Watercolor Wisconsin 2015

Photography: Jon Bolton

Kenosha artist Carlotta Miller, whose work has been featured in more than one Watercolor Wisconsin exhibition at RAM’s Wustum Museum, uses watercolor to translate scenes into poetic images that emphasize color as much as form. Miller credits the results to her interest in the seemingly different processes of printmaking and watercolor painting. About her working methods, she states:

I’m drawn to the process of making prints and the spontaneity of watercolors. [This] has allowed me to develop an affinity for the intriguing results of poured watercolor. As I explore this process and the discipline needed in using a limited palette, I continue to be surprised by the randomness of transparent watercolor.

Myra Mimlitsch-Gray

Pitcher with Oval Handle, 1998

Sterling silver

5 7/16 x 5 x 4 1/2 inches

Racine Art Museum, Gift of Karen Johnson Boyd

Photography: Jon Bolton

My work exists as homage and critique as it engages traditional objects, their purpose and presence in contemporary society…Exploring craft’s social function and identity continues to motivate my investigation of new forms. I locate the pieces I make in the domestic sphere: mantel, sideboard, table. Their implied purposes drive the content of my work.

Myra Mimlitsch-Gray blends her academic knowledge of metalsmithing and her desire to understand objects and materials in a singular way by upending concepts of both. While her career output to-date has included non-functional objects based on functional objects, as well as jewelry and sculptural objects, her investigations are often theoretical in nature as she manipulates form and content. In RAM’s collection, Mimlitsch-Gray’s sterling silver Pitcher with Oval Handle has exaggerated hammering marks that reflect her capacity to play with these ideas. She has magnified the planishes—marks that historically signified the human hand in production—to draw attention to the tension between handcrafted traditions and industrial manufacturing. Intentionally and necessarily, Mimlitsch-Gray’s process differs from the traditional techniques. Her intent is not the same; she embarks on an investigation of meaning and relationships, not the creation of a functional object in a formal sense.

An applauded artist, Mimlitsch-Gray is the recipient of numerous awards, and her work is collected nationally and internationally. She has been a Professor at the State University of New York-New Paltz for some time and uses that opportunity to encourage young artists:

I want them to discover their own approach to this vocabulary of objects…The way issues of identity can be explored and expressed through objects is important.

Norma Minkowitz

Hide Me, 1995

Cotton, shellac, paint, resin, and tree branch

30 1/2 x 15 x 9 inches

Racine Art Museum, The Cotsen Contemporary American Basket Collection

Photography: Michael Tropea, Chicago

I often dwell on the mysterious cycles of death and regeneration. In many of my works twigs and branches are left inside and are visible in an eerie way through the exterior of the sculpture, often suggesting connections to the human skeletal or circulatory systems. The outer netting obscures the shape within creating a sense of ambiguity in the shadows of the work. On the surface, paint and stitched lines appear and disappear depending on the light and viewing position. Intricate and random patterns are created by the nature of the open mesh structures. All of these elements combine to convey a sense of energy as the viewer moves around my sculpture. Conceptually, the interlaced fibers can lend a wonderful duality—simultaneously creating a delicate quality, but also implying the strength of steel mesh—symbolic of the human condition.

Norma Minkowitz’s artistic output includes fiber sculpture, art to wear, portraits, drawings, and two-dimensional fiber. A graduate of the Cooper Union Art School, New York, New York, she first gained success with art to wear in the 1970s. Minkowitz has pushed the boundaries of handcraft textile techniques and has the accolades, exhibition history, and collection representation to reflect her efforts. RAM currently holds eight works by Minkowitz—a blend of figural work such as Hide Me and container forms that the artist regards on a metaphorical level.

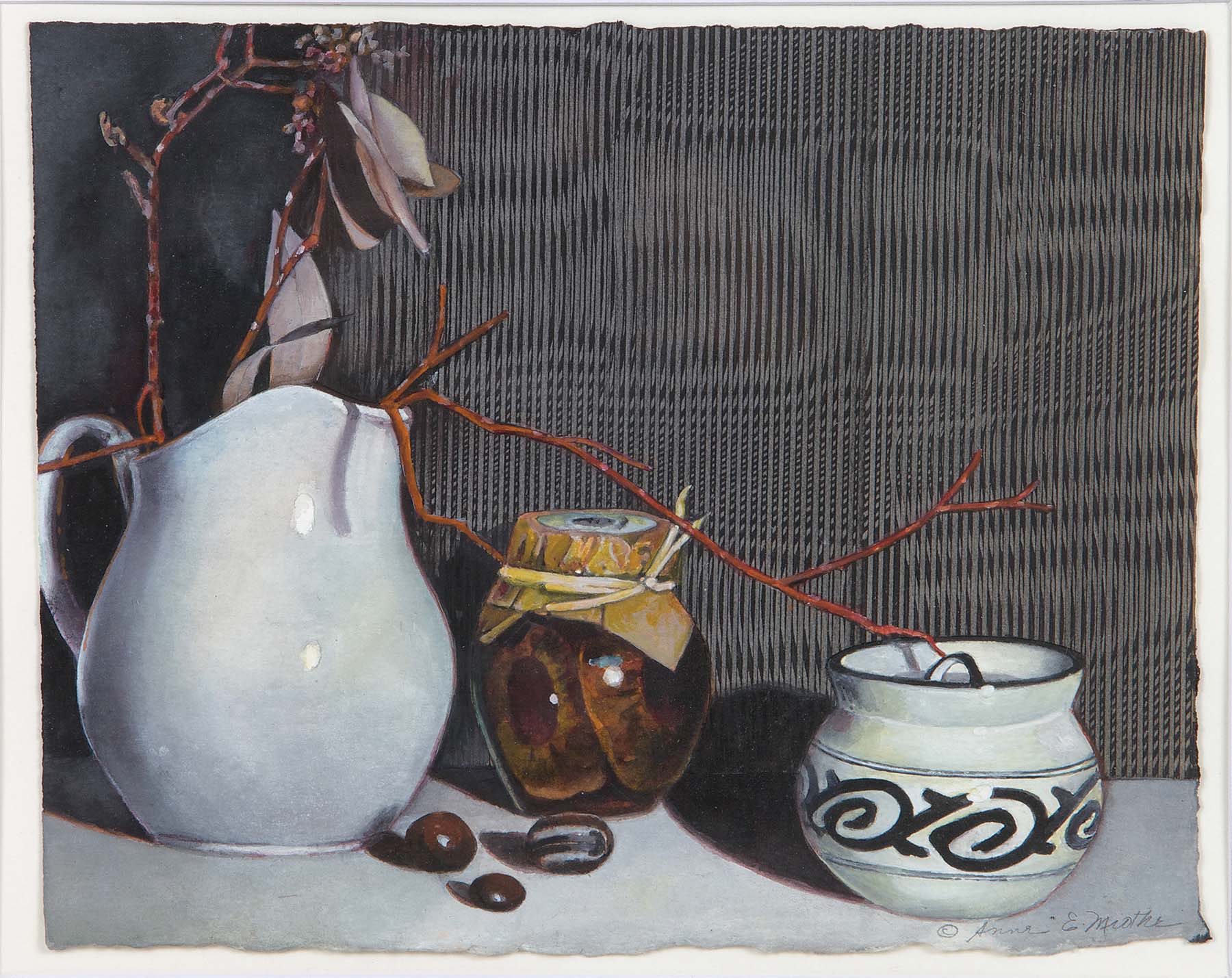

Anne Miotke

Red Branch, 2010

Watercolor

19 x 23 inches

Racine Art Museum, George and Betty Ren Frederiksen Purchase Award from Watercolor Wisconsin 2010

Photography: Jon Bolton

Playing on painting traditions that use light, shadow, and juxtaposition to add layers of meaning, Anne Miotke creates watercolors of still life subjects. Miotke has often incorporated objects gathered during her travels in her work, stating that such things “reveal personal history and introduce the concept of artist as collector.” Born in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, she has taught in the area for decades while simultaneously exhibiting her work in national and international venues. A frequent contributor to the annual Watercolor Wisconsin competition, Miotke is also represented in RAM’s collection by several pieces.

Holly Anne Mitchell

The Joke’s On You! (Bracelet), 1992

Found colored newspaper, brass beads, elastic, and cotton cord

1 3/4 x 5 x 2 1/2 inches

Racine Art Museum, Gift of Dale and Doug Anderson

Photography: Jon Bolton

For 30 years, I’ve had an endless fascination with newspaper. It began with an assignment in a metalsmithing class to create a piece of jewelry which did not consist of any traditional materials (no metal, precious stones, etc.). I chose newspaper. I love to push the boundaries of its text, color and content… I use Comic Strips because the characters’ expressive faces contain bold, bright and powerful colors. I use Expired Coupons because the textural patterns of many elements including the UPC Bar Codes are reminiscent of African Kente cloth. I strive to bring out these aesthetic strengths to create jewelry which is equally interesting both on and off the body. I truly believe the ordinary (such as newspaper) can be extraordinary.

Holly Anne Mitchell uses recycled newspaper to create beaded bracelets, brooches, necklaces, and earrings that speak to eco-friendly practices as well as challenge assumptions about which materials can be used for jewelry. Mitchell is inspired by social and cultural issues as well as material and aesthetic ones. The tone of her work can range from playful—as is the case with Mitchell’s bracelet in RAM’s collection, The Joke’s On You!––to serious. Her I Can’t Breathe Neckpiece incorporates newspaper with articles and images regarding the death of George Floyd. As she states:

It is a direct reflection and expression of my emotional response to this horrific, senseless death. As an African American, I felt a deep connection to Mr. Floyd. If it happened to Mr. Floyd, it could certainly happen to any and every African American man in my life.

Frances Myers

Bethesda RKO, ca.1975

Color etching, edition 8/30

27 7/8 x 21 3/4 inches

Racine Art Museum, Gift of Karen Johnson Boyd

Photography: Jon Bolton

Attributing an interest in architectural forms to early influences, Racine native Frances Myers (1936–2014) created prints that often used space, geography, and form as subject. Not bound to only those themes, however, Myers experimented with new graphic processes, collage elements, social and cultural issues, and installations.

A descriptive tribute offered upon her retirement is worth repeating here:

She balanced…male bravado with feminine grace and strength. She was the ideal role model for hundreds of women students over the years. She never shied away from injustice. As a student, I was constantly in awe of her ability to teach in heels and designer skirts. Fran’s beauty is both physical and spiritual. She has been the undying, loyal supporter of current and past students. She taught us much about community and generosity …and we will never forget her laugh or that all-knowing glance over her eyeglasses.

– Louise Kames

Myers studied at the San Francisco Art Institute before transferring to the University of Wisconsin-Madison where she earned both MA and MFA degrees. She taught printmaking at the University of California-Berkeley and Mills College in California. Beginning in 1975, she taught at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, eventually becoming Chair of the Graphics Department. She was married to fellow printmaker Warrington Colescott.

Emiko Oye

Dawning (Neckpiece), 2010

Lego® pieces, silk, and coated copper wire

11 x 8 x 2 1/2 inches

Racine Art Museum, Gift of Gail M. Brown

Photography: Christine Dhein

Motivated by the gift of a number of LEGOs many years ago, Emiko Oye began to make jewelry—primarily neckpieces—based on historical royal examples. The irony of recreating luxury with a democratic, commonplace material is humorous and poignant, suiting the artist’s exploration of how and why we value certain items. Repurposed materials also offer narrative and storytelling capabilities as they can contain memories and meanings—an attribute with which Oye plays. Her inspirations are wide-ranging and include art history, David Bowie, haute couture, and social dynamics such as nonviolent communication. Within her practice, Oye creates one-of-a-kind conceptual jewelry, operates her ready-to-wear jewelry business named emiko-o, conducts practical workshops for jewelers, and teaches yoga. LEGO, with whom she has collaborated on various projects, identified Oye as a top “’Influencer’ for young female makers.”

Oye’s piece in RAM’s collection, Dawning, and a companion work not in the collection, were inspired by a 1959 assemblage by Louise Nevelson entitled Dawn’s Wedding Feast. Oye echoes the white coloration and the pieced-together aesthetic of Nevelson’s sculpture. These neckpieces are part of a series that reinterpret historical works she encountered on visits to San Francisco art museums.

Lindsay Pichaske

The Jackal, 2013

Earthenware, glass, steel, and hand-dyed found chicken feathers

50 1/2 x 31 x 11 inches

Racine Art Museum, Gift of David and Jacqueline Charak

Photography: Jon Bolton

What separates human from animal? What borders exist between the real and the imagined, the beautiful and the repugnant, the living and dying, the creator and the made? Through the act of making, I swim in and around these margins, revealing how slippery the answers to these questions are. I create animals that blur species boundaries…The labor I exert over the animal becomes an empathetic gesture…the sense of parental love I feel for my creations is undeniable. I spend endless hours stroking hair onto their backs, arranging the fur on their heads, looking into their eyes to make sure they are just right. My process is a labor of love, as I give impossibly slow birth to each one, and they, in turn, develop lives of their own.

A stand-out in contemporary ceramic sculpture, Lindsay Pichaske creates compelling creatures that offer contemplation across species. She combines unusual materials—such as human hair, flocking, molted feathers, charcoal, foam, sequins, monofilament, wax, artificial flower petals, string, and rope—with low-fired ceramics to create lifelike skins. Pichaske’s piece in RAM’s collection, The Jackal, is covered in hand-dyed, naturally molted chicken feathers.

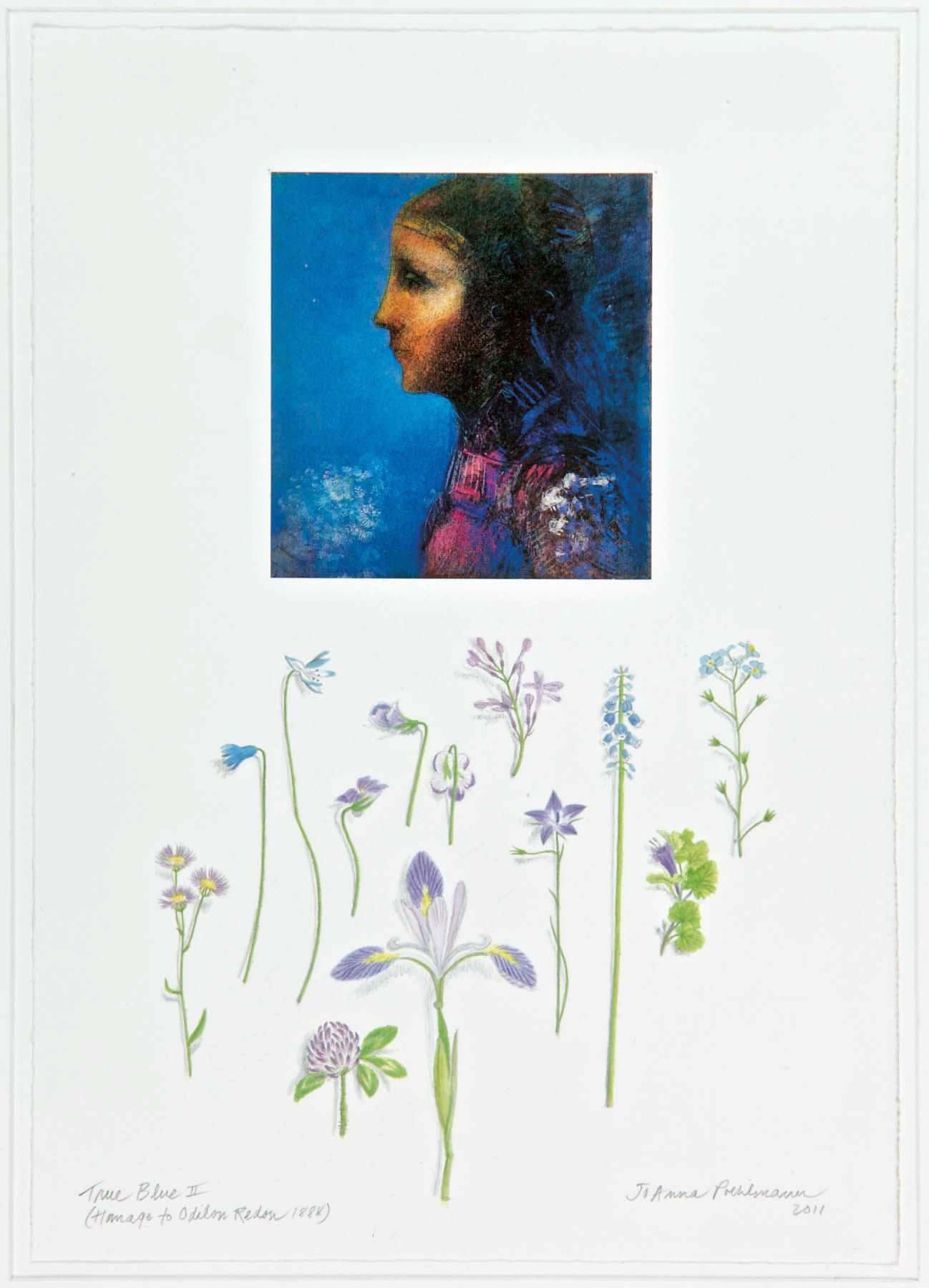

JoAnna Poehlmann

True Blue II (Homage to Odilon Redon 1888), 2011

Watercolor, graphite, and collage

Racine Art Museum, Ruth Miles Memorial Purchase Award from Watercolor Wisconsin 2011

Photography: Jon Bolton

Well-known Wisconsin painter, printmaker, illustrator, and collector of natural world treasures, JoAnna Poehlmann is also known for her dry sense of humor and clever word play. Poehlmann’s two-dimensional works and artists’ books can be found in museum and library collections around the world. She is one the 50 most collected artists in RAM’s collection and has earned awards in 14 of the last 32 years of annual Watercolor Wisconsin exhibitions. Her work has also been shown in several solo shows over the years at both the RAM and Wustum campuses. Poehlmann’s admiration for the natural world is apparent in this quote from an article published in American Craft Magazine in 2019:

People think toads are so ugly. I think they’re so beautiful. God worked just as hard on those as he did on a hippopotamus. A little machine is in there, and it’s working, and it’s doing its thing, you know? It’s amazing.

Donna Rosenthal

My Fair Ladies: The Free Spirit, 2011

Found vintage atlases, found vintage buttons, and steel

20 1/8 x 13 x 12 inches

Racine Art Museum, Gift of Gregg, Terrie, and Kirsten Maki in Honor of Emily Therese Maki

Photography: Jon Bolton

I observe and examine the nature of relationships, gender roles, and social positions. Using text, repetition, and the cultural symbolism of clothing, I reveal the struggles between the internal and external self, exposing the distinctions, expectations, conflicts, and joys that exist for individuals and between the sexes. As a child, I was surrounded by untraditional art and craft materials in my parents’ window display store. Sequins, glitter, antiques, display cases, manikins, and a host of sparkly wonders triggered my imagination, and played an important role in my artistic interpretation, the content of the work, and the development of my own personal language.

Donna Rosenthal explores identity—primarily that of females—through text and metaphor. She earned a BA in education in the 1970s and an MFA in Mixed Media Sculpture over 20 years later. Rosenthal has been exhibiting internationally since the 1980s. Her work reflects the persistent need for individuals to define and re-define themselves through social constructs.

ROY

Nectar Walkers (Liqueur Cups), 1992

Sterling silver, brass, and garnets

Various dimensions

Racine Art Museum, Gift of Karen Johnson Boyd

Photography: Jon Bolton

With degrees in drawing and metalsmithing, ROY (previously Rosemary Gialamas) creates objects and jewelry that reflect her knowledge and history of art and various cultures as well as a signature playful approach. She explores a range of subject matter—from Greek and American cityscapes to paintings to gender—while utilizing diverse media such as laminated imagery and found rubber duckies as well as metals.

About her choice to use metal to make certain kinds of work, she states:

I am questioned about hot metal in the hands of a woman. Isn’t it too dangerous for such delicate hands? Women can handle anything they set their minds to.

Joyce Scott

Procreation (Neckpiece),1994

Glass beads, thread, and wire

11 1/4 x 11 5/8 x 1 3/4 inches

Racine Art Museum, Gift of Dale and Doug Anderson

Photography: Jon Bolton

It’s important to me to use art in a manner that incites people to look and then carry something home—even if it’s subliminal—that might make a change in them.

Perhaps best known for her beaded sculpture and adornment—though ultimately not bound by media—Joyce Scott does not shy away from addressing complex social, cultural, and political issues in her work. Scott’s heritage—she identifies African Americans, Native Americans, and Scots as ancestors—as well as her familial connections to quilters, basketweavers, story tellers, and other makers are cited as both resources and inspiration. Indeed, her quiltmaking mother not only taught her quilting techniques but also encouraged her to be an artist.

Named a MacArthur Fellow in 2016 and a Smithsonian Visionary Artist in 2019, Scott has been at the forefront of contemporary craft—pushing boundaries and upending expectations—for decades. Her beaded work is a combination of free-form and off-loom processes that allow her to create representational figures and narrative scenes. Procreation, one of several works by Scott in RAM’s collection, draws attention to the complex web of ideas associated with a woman’s body, fertility, and gender roles. An elaborate yet wearable neckpiece, this work is adornment with a message—the wearer becomes a collaborator with Scott or, in her words, a “walking billboard” for her thoughts.

Video courtesy of Craft in America

Yoko Sekino-Bové

Village Expert Teapot from the Genuine Fake China Series, 2010

Porcelain with lustres

Racine Art Museum, Gift of the Artist

Photography: Yoko Sekino-Bové

Yoko Sekino-Bové was born in Osaka, Japan. She graduated with a BFA in Graphic Design from Musashino Art University in Tokyo, Japan, and worked as a designer in Los Angeles before focusing on ceramics. She received an MFA in Ceramics from the University of Oklahoma. Her work has been featured in numerous publications and exhibitions.

RAM’s teapot and cups are a part of her Genuine Fake China Series. Of that series, she states:

This series is my quiet resistance against the current political situation in our time, of isolation and confrontation. Seems like we can use more of those reminders about how similar we are now than ever by exchanging stories and using small conversations, instead of abstract fear and anger. Many conflicts start with the fear of unknown, which can be reduced easily by getting know each other. If we learn the strangers eat like us, think like us, and live like us, I think we can relax a bit more.

Thus my Genuine Fake China series come with two sides: one with Chinese/Japanese proverb, another with English equivalent (or a saying that has the same nuance). It is my attempt to construct a bridge over the gap and start conversations about so many profound ideas we share even in different periods, languages and cultures. While learning American English, I discovered that proverbs are an essence of the culture/language the people use, a condensed reflection of their philosophy. If there is a proverb in two languages that shares the same idea, I can comfortably say those two group of people think alike, at least on the specific subject. If the saying exists in multiple cultures, it would be a great proof that it’s a universal idea.

Berta Sherwood

The Catch, 1974

Watercolor

21 3/4 x 29 3/4 inches

Racine Art Museum, Gift of the Junior League of Racine

Photography: Jon Bolton

Echoing the history of watercolor as a medium used to record experiences, Berta Sherwood (1916–1997) often painted scenes that she had photographed, sketched, or memorized as she traveled. Sherwood received a BA in fine arts from Colorado College. She also studied at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and the American Academy of Art. Sherwood was a frequent contributor to annual Watercolor Wisconsin exhibitions and taught watercolor at Wustum for decades in both master’s workshops and open painting studios.

Installation View of Red Pinafore from Diane Simpson: Window Dressing in the Windows on Fifth Gallery, 2007

Photography: Michael Tropea, Chicago

One of the components of Diane Simpson’s 2007 Windows on Fifth Gallery exhibition became part of RAM’s collection. Entitled Pinafore, the wood and cotton sculpture accented with vintage wallpaper, reflects Simpson’s interest in the relationship between structure, design, and architecture. Clothing, furniture, and other utilitarian objects often serve as her source material and subject matter—a dynamic reflected in this particular piece and the 2007 Windows exhibition as a whole. Simpson’s career path—as articulated in a 2020 article by Chloe Steadon on artnet.com—has been punctuated with, “later-in-life success.”

A portion of that story is quoted here:

Not long after her inclusion in last year’s Whitney Biennial—where she was the oldest artist in a show dominated by millennials—Simpson has also just opened a solo exhibition at Nottingham Contemporary, her first institutional show in Europe…

But Simpson doesn’t seem to mind her later-in-life success, although she understands that many in her position might not have stuck with it for so long. “I had a lucky situation,” she says. “My husband, I should say, was very encouraging. I realize how tough it is. For so many young artists, it’s really difficult to do their art and also earn a living and they have to either spend a lot of time teaching or have another job.”

The spotlight on Simpson’s work comes at a time when the art world is taking a renewed interest not only in the Chicago Imagists—many of whom she studied alongside her at the Chicago Institute of Art—but also in older women artists in general who may have been structurally shut out of the art market because of their gender in the past.

Simpson says she was always on the periphery of Imagists and was never included in those early Imagist exhibitions at Hyde Park Art Center in Chicago. “I think for the most part, stylistically and in regard to subject matter, my work was very different from that of the Imagists,” she says. “I feel closest to [Chicago Imagist] Christina Ramberg—her imagery and interests are similar to mine, both being drawn to clothing and the body.Indeed, there are certainly similarities between the two. Ramberg, like Simpson, made detailed preparatory drawings for her work based on divergent source material. And, like Ramberg, Simpson doesn’t see her practice as overtly feminist, although she accepts that her way of working is affected by her experience, “as a woman and as a mother.” If she mainly uses female garments as source material, she says, it’s only because it’s more interesting than what men traditionally wear, rather than to serve, “any political agenda.

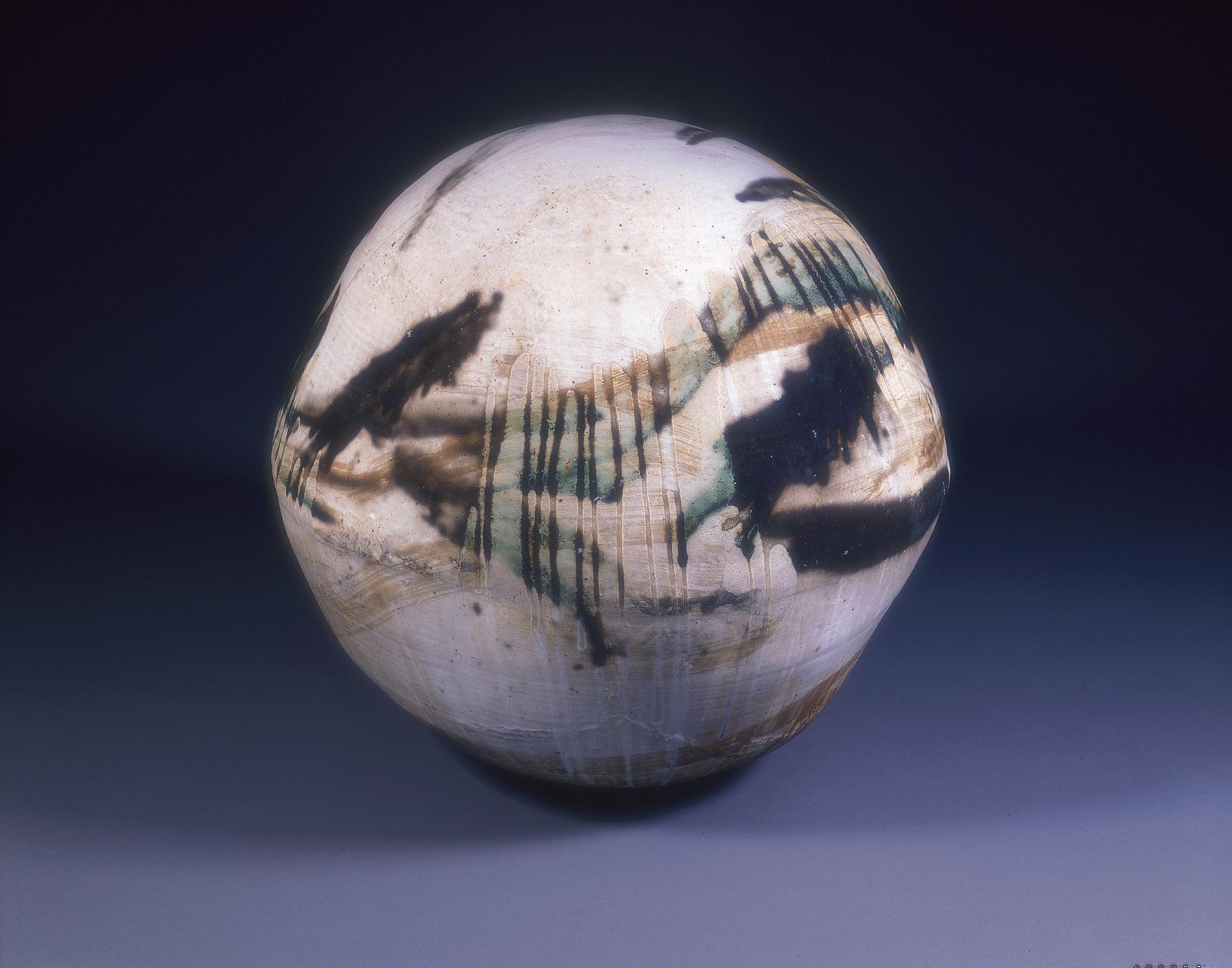

Toshiko Takaezu

Mondo, 1989

Glazed stoneware

26 x 25 inches diameter

Racine Art Museum, Gift of the Artist and Karen Johnson Boyd in Memory of Samuel C. Johnson

Photography: Michael Tropea, Chicago

You are not an artist simply because you paint or sculpt or make pots that cannot be used. An artist is a poet in his or her own medium. And when an artist produces a good piece, that work has mystery, an unsaid quality; it is alive

Boundary-breaking and extremely influential, Toshiko Takaezu (1922-2011) set a new standard for what clay could do as a material and as an idea. RAM became a favorite place for the artist and, ultimately, the repository of more than 30 works created throughout her career, including her largest and most significant installation, the Star Series. Takaezu’s legacy encompasses not only her work but also her willingness to share her wisdom. Her studio, and, really, anywhere she was, became a place of inspiration.

Dorothy Torivio

Vessel, 1981

Glazed earthenware

1 x 2 1/4 inches diameter

Racine Art Museum, Gift of Karen Johnson Boyd

Photography: Jon Bolton

My brain is my computer.

Acoma potter Dorothy Torivio (1946–2011) gained recognition for eye-dazzling, high contrast designs on ceramic pots, vessels, bowls, and figures. Torivio’s working process included formulating a pattern in her head before applying her brush to an object’s surface. She established her own style with particularly complex patterns that take advantage of the optical play of positive and negative space. The quote above is the artist’s response when a mathematics professor told her it took him a long time to work out her designs on his computer.

While her aesthetic is innovative, Torivio followed some Pueblo traditions as a member of a network of women in her family who make pottery, build ceramic forms by hand—specifically through coiling—and fire pieces in pit kilns outdoors. Garnering numerous awards, Torivio drew attention for the way she blended tradition and experimentation. Her work was featured in numerous exhibitions, and she ultimately traveled across the US, demonstrating her process and teaching.

RAM currently has two works by Torivio in the collection—each exemplifying the elaborate designs that became her hallmark. These works, along with others made by various Pueblo potters, reflect RAM’s desire to share diverse voices in contemporary craft.

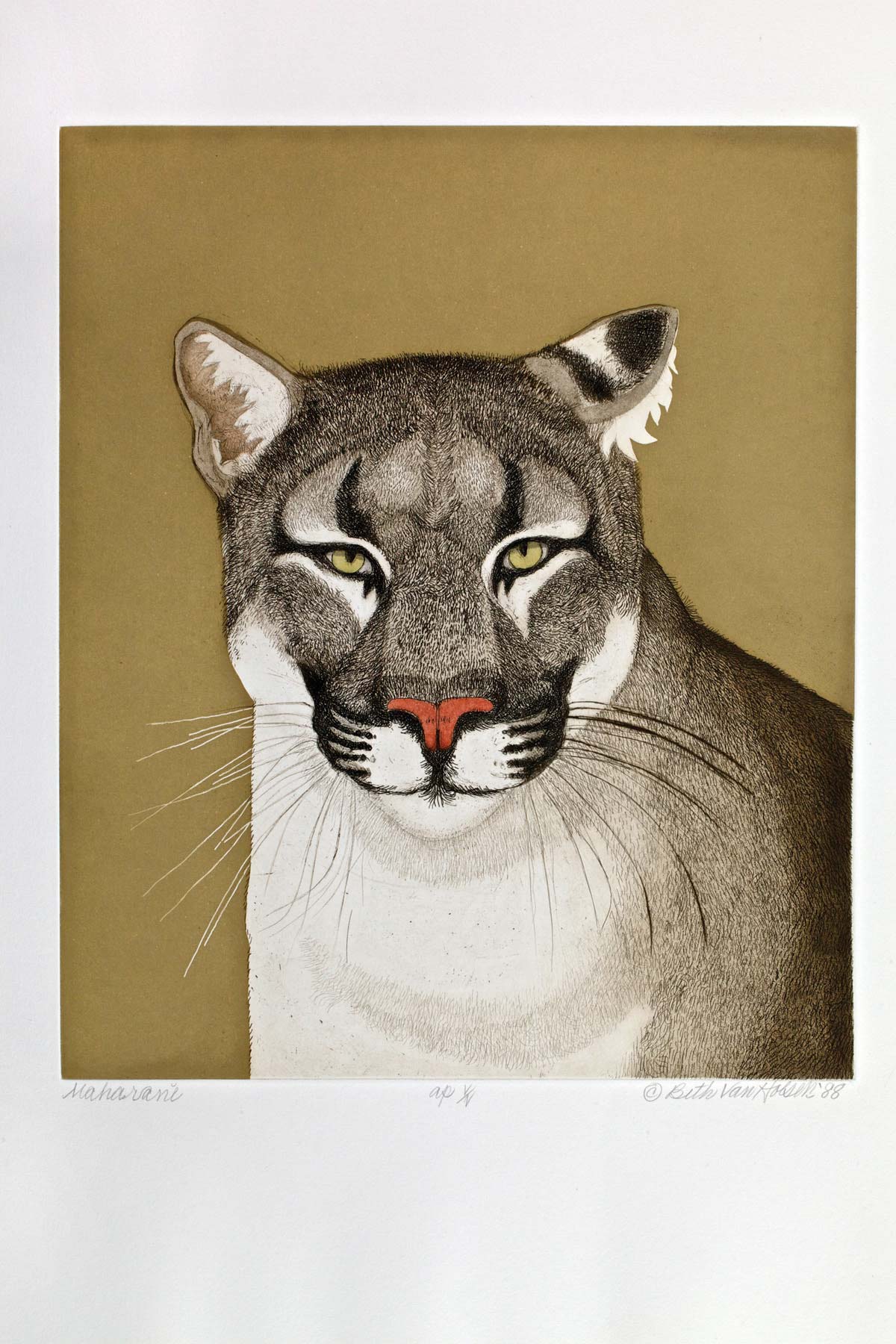

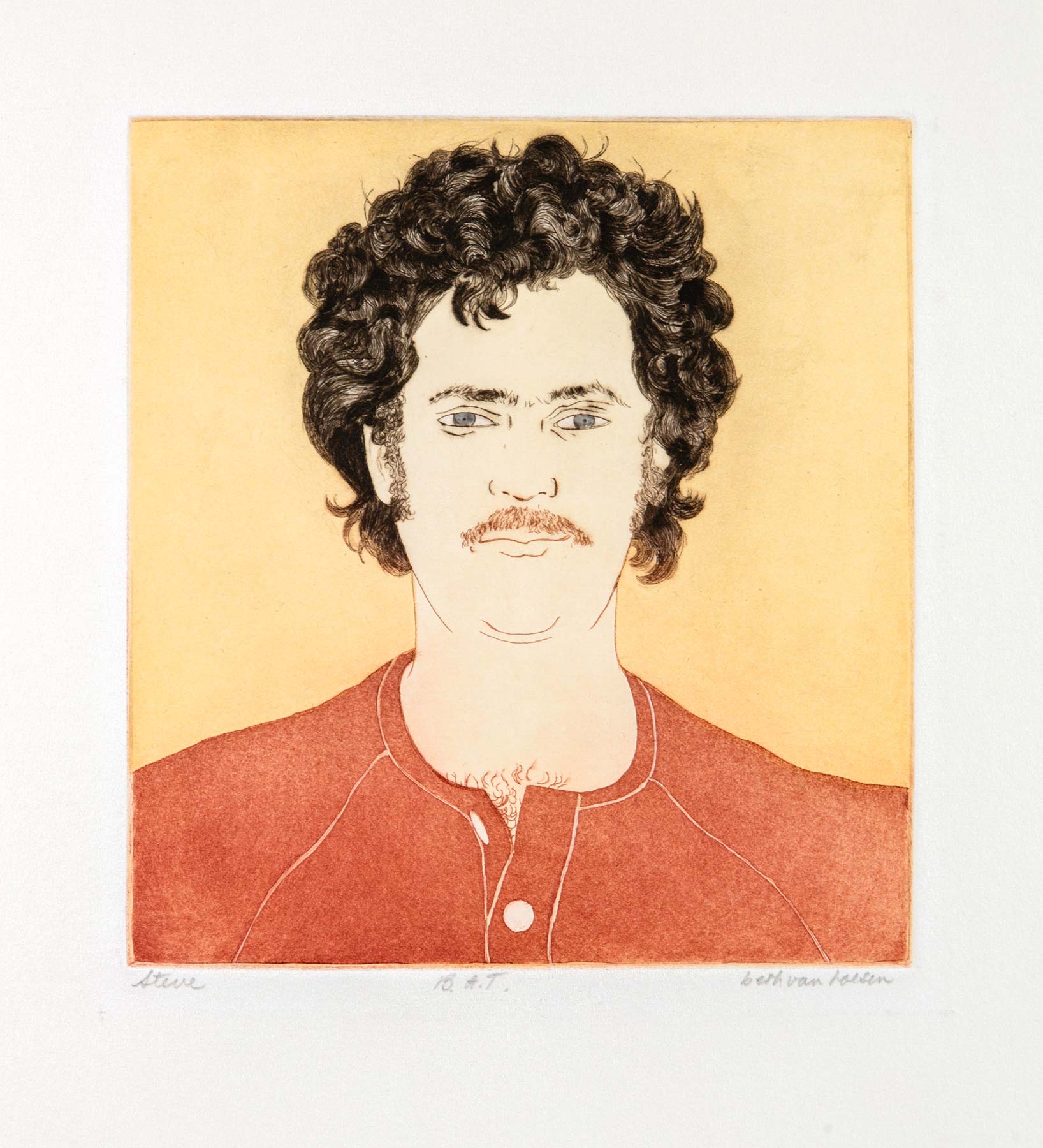

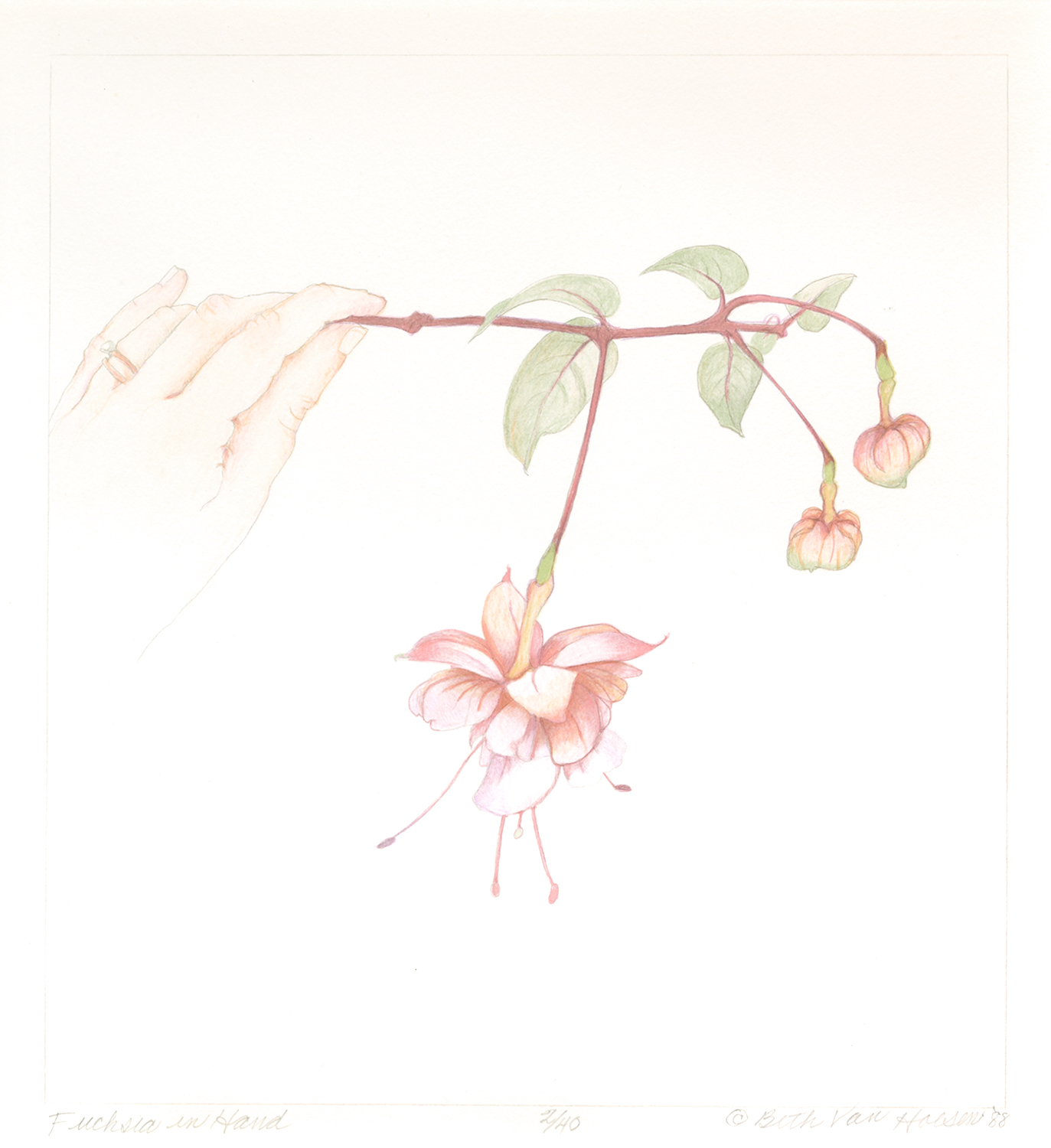

Beth Van Hoesen

Fuchsia in Hand, 1988

Color lithograph, edition 6/40

12 3/4 x 11 5/8 inches

Racine Art Museum, Gift of the E. Mark Adams and Beth Van Hoesen Adams Trust

Photography: M. Lee Fatherree

I’ve always drawn pictures. Before I was seven, I lived on an apple orchard my family owned in Idaho. There were lots of things to draw there, but I drew only people—the children at the one-room schoolhouse or the apple pickers at work—many little people all over the page…In all the many schools I attended, there were few art classes. When I was recovering from a long illness and had to stay inside, I drew from pictures in books and magazines. My first art lesson using oils was given to me by a California desert painter who lived next door. He had me copy a reproduction of a portrait of Walt Whitman by Thomas Eakins. When I look back, I realize that I learned a great deal from copying—studying a painter by looking at each brush stroke One of my favorites, Degas, also learned from copying in museums.

Throughout her career, Beth Van Hoesen (1926–2010) distinguished herself as a major figure in twentieth-century printmaking. She is nationally known for her realistic images of animals, floral studies, figure drawings, and portraits. Van Hoesen—represented to date at RAM with 307 works including prints, watercolors, drawings, and metal printing plates—holds the honor of being RAM’s most-collected artist regardless of media. Her archive at the museum offers numerous examples in which the life of a print from start-to-finish may be traced through multiple stages and various media.

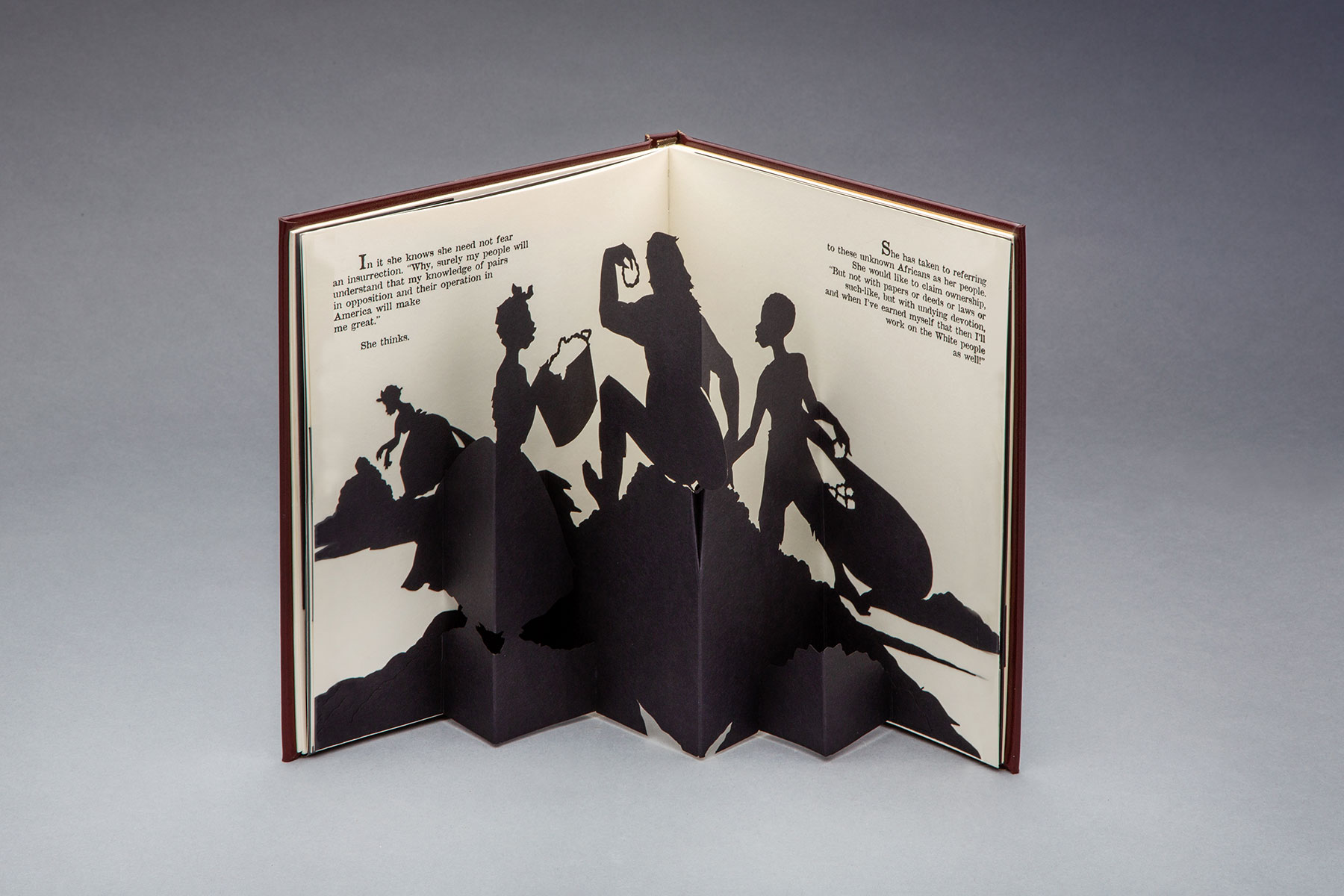

Kara Walker

Freedom: A Fable—A Curious Interpretation of the Wit of a Negress in Troubled Times, 1997

Offset lithograph, dyed leather, and laser-cut paper, Artists’ book, edition of 4,000

9 1/4 x 8 3/8 inches

Racine Art Museum, Gift of Peter and Eileen Norton and Family

Photography: Jon Bolton

I’m not really about blackness, per se, but about blackness and whiteness, and what they mean and how they interact with one another and what power is all about…Challenging and highlighting abusive power dynamics in our culture is my goal; replicating them is not.

First known for large-scale tableaux of cut paper silhouettes, Kara Walker has utilized a broad range of media in her practice including silhouettes, prints, film, video, and installations. Walker’s thought-provoking investigations of race, sexuality, history, gender, and identity engage on many levels. Often playing off of stereotypes and the misconceptions they can lead to, Walker has—by design—encouraged a wide range of responses from a wide range of viewers. As she states:

I didn’t want a completely passive viewer. Art means too much to me. To be able to articulate something visually is really an important thing…I wanted to make work where the viewer wouldn’t walk away…

Walker’s book, ultimately a pop-up with its dimensional pages, crosses media boundaries in RAM’s collection as a work on paper, an artists’ book, and an object. Her piece also subverts expectations in that it combines a popular children’s book format with a complex, layered narrative. This kind of work, which operates in between categories, can be pivotal in encouraging conversations about assumptions and relationships, where compositional choices become metaphors for society. While her installations and larger works envelop visitors, this book pulls viewers into a smaller, more intimate—yet no less powerful—space. From there, Walker offers a narrative about freedom through the eyes of a female slave.

Kara Walker received a BFA from the Atlanta College of Art and an MFA from the Rhode Island School of Design, Providence, Rhode Island. Currently the Tepper Chair in Visual Arts at the Mason Gross School of the Arts at Rutgers University, New Brunswick, New Jersey, her work has been exhibited extensively and can be found in museums and public collections internationally. She is the recipient of many awards, including the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation Achievement Award.

Lee Weiss

Autumn Ridge, 1966

Watercolor

30 x 40 inches

Racine Art Museum, C.W. DeWitt and W.H. Keland Purchase Award from Watercolor Wisconsin ’66

Photography: Jon Bolton

Inspired by the natural world, Lee Weiss (1928–2018) became nationally known for her watercolors during the second half of the twentieth century. Shifting back and forth between macro and micro views of the landscape and its essence, Weiss experimented with technique. She painted on both sides of a piece of paper to introduce various textures and remove wet washes with a dry brush. Weiss built up a lengthy exhibition history and has works in a number of collections including the Smithsonian National Museum of American Art and the Phillips Collection in Washington, DC. She is currently represented at RAM by eight works.

Toots Zynsky

Untitled #9, ca. 1990

Glass

4 7/8 x 9 3/4 x 8 7/8 inches

Racine Art Museum, Gift of Holly Hotchner and Franklin Silverstone

Photography: Jon Bolton

I still think that one of the best ways to learn about glass—and to start to have a deep understanding of it—is by blowing it…You learn that you have to work with glass, that you can’t just impose your desires on it, because it’s always doing something on its own. Glass moves, it’s hot, and you have to be moving with it. It breaks pretty quickly if you don’t do the right thing, which is one of the qualities about glass that I find strangely positive—the fact that it breaks.

Mary Ann “Toots” Zynsky was born and raised in Massachusetts. Known professionally and to her friends as Toots, she received a BFA in 1973 at the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD) in Providence, where she studied with internationally renowned glass artist Dale Chihuly. She later participated in the founding of the Pilchuck Glass School in Washington with Chihuly and other artists. Zynsky was a pivotal figure in the early experimental days of studio glass, producing—alongside others—video and performance works incorporating various kinds of glass. In 1980, she became assistant director and head of the hot shop at the New York Experimental Glass Workshop in New York, New York.

Zynsky pioneered and further developed a distinctive method known as filet de verre, meaning “glass thread,” which allows for compelling explorations of color as well as texture in a variety of shapes and sizes. Her vessels in RAM’s collections underscore Zynsky’s engagement with the media and the process.

RAM Introduces

In recognition of the 100th anniversary of the 19th Amendment of the United States Constitution granting women the right to vote, RAM Executive Director and Curator of Collections Bruce W. Pepich introduced 21 women artists in the museum’s permanent collection throughout 2020—including Mary Bero, Mara Superior, Toshiko Takaezu, and Elise Winters—in a series of short, educational videos titled RAM Introduces. You are invited to watch all videos in this now-continuing series on the RAM YouTube channel.

RAM Introduces

In recognition of the 100th anniversary of the 19th Amendment of the United States Constitution granting women the right to vote, RAM Executive Director and Curator of Collections Bruce W. Pepich introduced 21 women artists in the museum’s permanent collection throughout 2020—including Mary Bero, Mara Superior, Toshiko Takaezu, and Elise Winters—in a series of short, educational videos titled RAM Introduces. You are invited to watch all videos in this now-continuing series on the RAM YouTube channel.

More Work from RAM’s Collection by Women Artists

Click/tap an image for more information

Stay in Touch

The Racine Art Museum and RAM’s Wustum Museum work together to serve as a community resource, with spaces for discovery, creation, and connection. Keep up to date on everything happening at both museum campuses—and beyond—by subscribing to our email newsletter: